Ever tried to draw a perfectly straight line on a piece of paper? You can't. Not really. What you’re actually drawing is a tiny, smudged physical representation of a concept that exists only in the realm of pure logic. Most of us carry around a fuzzy memory of high school math where we learned about the line segment ray line trifecta, but honestly, the nuance gets lost between the homework and the real world. We treat them like they're interchangeable. They aren't.

Geometry is the bedrock of everything from the GPS in your pocket to the way your house stays upright during a storm. If you don't get the difference between a segment and a ray, you're going to have a hard time understanding how light reflects off a mirror or how a computer renders a 3D character in a video game. It’s not just pedantic vocabulary. It’s the language of the universe.

The Line: The Infinite Nightmare

Think about infinity. It’s hard, right? A line in geometry is a one-dimensional figure that has no thickness and extends infinitely in both directions. It literally never ends. You can’t measure a line. How do you measure something that goes on forever? You don't. You just describe its slope or its position in space.

In standard Euclidean geometry, we represent this with arrows on both ends. This tells the viewer, "Hey, this thing keeps going past the edges of the page, past the moon, and past the edge of the observable universe." It’s an abstraction. In the real world, we don't have "lines" in the mathematical sense because everything has a beginning and an end. Even the horizon is just a curve.

Euclid, the father of geometry, defined a line in his work The Elements as "breadthless length." It’s a wild concept. Imagine something that has location and direction but occupies zero volume. When you’re looking at a line segment ray line comparison, the line is the big boss—the infinite parent from which the others are carved out.

The Line Segment: Life in the Real World

This is where things get practical. A line segment is just a piece of a line. It has two distinct endpoints. You can measure it. You can hold it. Well, you can hold a ruler up to it, anyway. When you’re building a bookshelf or measuring your height, you are dealing with segments.

If you have point $A$ and point $B$, the line segment $AB$ is the shortest distance between them. It’s finite. It’s predictable. Most of the "lines" we talk about in daily life—the edge of a table, a pencil, the stretch of a highway—are actually line segments. They have a start, and they have a stop.

Interestingly, even though a segment is finite in length, it contains an infinite number of points. That’s the Zeno’s Paradox side of math. You can keep dividing that segment in half forever and never run out of points. But for the sake of your DIY project this weekend, just know that the segment is the part you can actually cut with a saw.

The Ray: The Beam of Light

A ray is the middle child. It’s got one endpoint (the origin) and then it blasts off into infinity in the other direction. Think of a flashlight or the sun. The light starts at the bulb or the surface of the star and travels until it hits something. In math, it doesn't even have to hit something. It just keeps going.

If you’re into coding or game development, you’ve definitely heard of "ray tracing." This is a huge deal in modern graphics. The computer simulates "rays" of light starting from a source and calculates how they bounce off surfaces. Without the mathematical concept of a ray, your favorite games would look flat and lifeless.

The notation matters here. If a ray starts at point $X$ and goes through point $Y$, you write it as $\overrightarrow{XY}$. You can't write it as $\overrightarrow{YX}$ because that would mean it starts at $Y$ and goes toward $X$. Direction is everything. It's a vector in the making.

Why the Distinction Actually Matters

You might think, "Who cares? It's all just straight marks." But precision is the difference between a bridge that stays up and one that collapses. Architects don't use lines; they use segments. Astronomers often use rays to track the path of cosmic radiation.

💡 You might also like: Apple Store Raceway Mall Freehold NJ: What to Know Before You Head Down

Mapping and Navigation

When your phone calculates a route, it’s using segments. A road isn't a line—it’s a series of segments connected at nodes (intersections). If the software treated roads as infinite lines, your GPS would be trying to send you into the ocean.

Physics and Optics

Refraction and reflection are all about rays. When light hits a prism, the incoming ray is bent into a new direction. Scientists like Sir Isaac Newton used these geometric definitions to map out the visible spectrum. If they hadn't been specific about the starting point and the infinite direction, the math for lenses—and therefore glasses and cameras—wouldn't work.

Common Misconceptions That Trip People Up

A lot of people think a line is just a "long segment." It's not. The difference is categorical.

- Size: A segment has a length. A line and a ray do not have a measurable length because they are infinite.

- Endpoints: A segment has two. A ray has one. A line has zero.

- Thickness: None of them have it. In the real world, a "line" drawn with a Sharpie is actually a very long, very thin rectangle. In math, they are strictly one-dimensional.

It’s easy to get lazy with the terms. We say "the finish line," but it's a segment. We talk about "lining up," but we're standing in a finite row.

✨ Don't miss: Mustafa Suleyman Net Worth: What Most People Get Wrong

Real-World Applications You Probably Missed

Let's talk about the line segment ray line dynamic in modern tech. In computer-aided design (CAD), engineers use these primitives to build everything. When an engineer draws a part for a jet engine, they are layering segments. But when they want to test how that engine reflects heat, they use rays to simulate thermal radiation.

Even in something as simple as a layout for a website, CSS and HTML deal with "borders" and "outlines." These are essentially segments. If you’ve ever used a "vector" graphic (like an SVG file), you’re using math to define those shapes instead of pixels. Vectors are based on the coordinates of points and the paths (segments and curves) between them. This is why you can zoom in on a vector logo forever and it never gets blurry. It’s pure geometry.

How to Keep Them Straight

If you’re helping a kid with homework or just trying to refresh your own brain, use these mental anchors:

- Line: Think of the horizon or the concept of eternity. No beginning, no end.

- Ray: Think of a "Ray" of sunshine. Starts at the sun, goes forever.

- Segment: Think of a "segment" of a grapefruit. It’s a piece. It’s got edges.

Geometry isn't just about shapes on a chalkboard. It’s a way of organizing the chaos of the physical world into something we can measure, predict, and build upon. The next time you see a "line" in the world, ask yourself if it’s actually a segment or a ray. Chances are, it's a segment pretending to be something more.

Actionable Steps for Mastering Geometry Basics

If you want to apply this knowledge or sharpen your spatial reasoning, start here:

- Identify the Endpoints: Whenever you see a linear path, look for the terminals. If there are two, it’s a segment. If it’s a beam of light, it’s a ray.

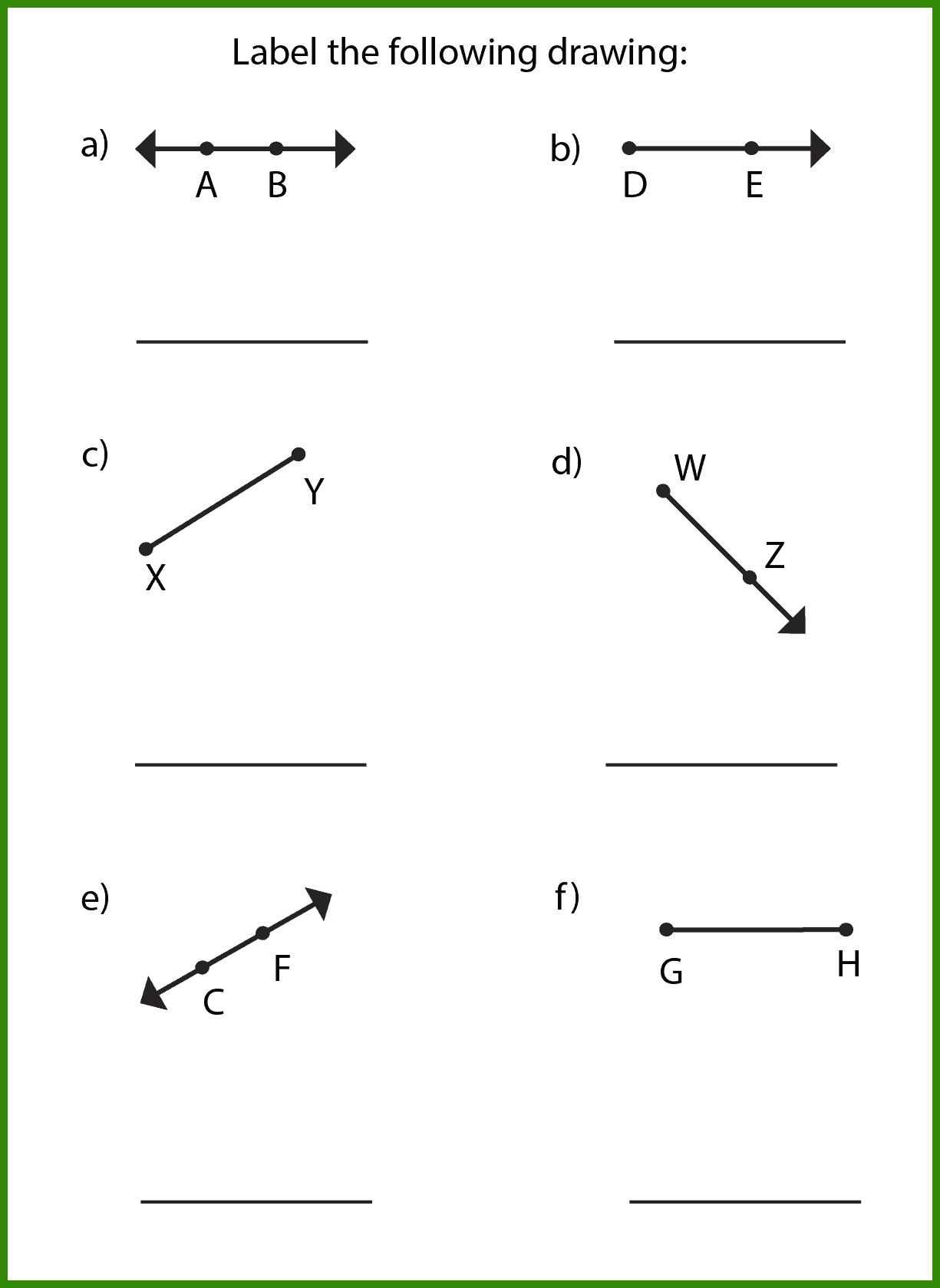

- Use Correct Notation: If you’re documenting a project, use an overline with no arrows for segments ($\overline{AB}$), one arrow for rays ($\overrightarrow{AB}$), and two arrows for lines ($\overleftrightarrow{AB}$). It prevents errors in communication with contractors or collaborators.

- Practice Vector Thinking: Download a free vector tool like Inkscape. Create shapes and look at the "nodes." You’ll see how segments and rays are used to define complex visuals.

- Verify Measurements: Remember that you can only provide a "length" for a segment. If a problem asks for the length of a line, the answer is "undefined" or "infinite." Don't let that trick question catch you off guard.