You’re sitting in a high school math class. The teacher scribbles a curly "e" on the chalkboard. Then they slap a "log" in front of it. Suddenly, you’re staring at log e, and if you’re like most people, your brain just kind of shuts down. It looks like a typo. It feels like a secret code. But honestly? It’s probably the most important mathematical constant in the history of human civilization.

Without it, your bank account wouldn't grow. Your phone wouldn't work. We wouldn't even be able to track how a virus spreads through a city.

Basically, when people ask about log e, they are usually stumbling into the world of the natural logarithm, often written as $\ln(x)$. It is the math of growth. It is the math of time. If you’ve ever wondered why things in nature don't grow in straight lines—why they curve and explode and then taper off—you’re looking at the thumbprint of $e$.

So, What Is This "e" Thing Anyway?

Before we can even talk about the logarithm part, we have to look at the number itself. It’s roughly 2.71828. Just a string of decimals that goes on forever without repeating. Boring, right?

Wrong.

Imagine you have one dollar in a bank account. This bank is insanely generous and gives you 100% interest per year. If they credit it once at the end of the year, you have two dollars. Simple. But what if they credit it every six months? You’d get 50% halfway through ($1.50) and then 50% of that at the end of the year. You end up with $2.25.

What if they did it every second? Every millisecond?

As you shorten the time between interest payments to an infinitely small sliver, your money doesn't become infinite. It hits a wall. That wall is $2.71828...$ or $e$.

It is the absolute limit of continuous growth. It’s the "speed limit" of the universe when things are growing based on their own current size.

The Relationship Between Log and e

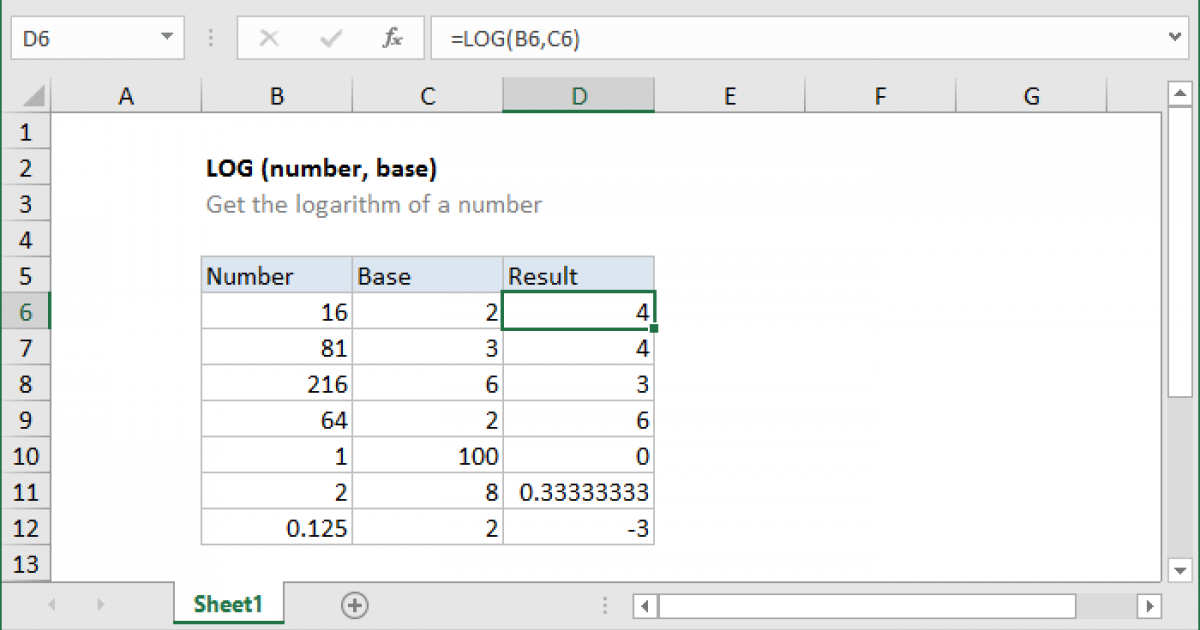

In math, a logarithm is just a fancy way of asking a question. If I write $\log_{10}(100)$, I’m asking: "To what power do I have to raise 10 to get 100?" The answer is 2.

So, when we talk about log e, we are usually talking about the natural logarithm. This is specifically $\log_e(x)$. In the math world, we call this $\ln$. It’s the inverse of growth.

💡 You might also like: How to Restart Phone: The Troubleshooting Trick Most People Mess Up

If $e$ tells you how much growth you get over a certain amount of time, log e tells you how much time it takes to reach a certain amount of growth.

It’s the undo button for exponential expansion.

If you have a population of bacteria doubling every hour, and you want to know exactly when you’ll have a billion of them, you aren't going to use a ruler. You’re going to use the natural log. You need to work backward from the result to find the time.

Why We Don't Just Use Log 10

You might wonder why we bother with this messy 2.718 number when we have perfectly good tens and hundreds to work with.

It’s about calculus.

If you graph $y = e^x$, the slope of that line at any single point is—wait for it—exactly $e^x$. It’s the only function in existence where the rate of change is the same as the value of the function itself. It’s perfectly symmetrical in its behavior.

Jacob Bernoulli was the first to really poke at this in the 1600s, but Leonhard Euler was the guy who gave it the name "$e$" and really figured out how deep the rabbit hole went. He realized that this number isn't just for money; it’s baked into the very fabric of physics.

Real World Chaos and the Natural Log

Think about carbon dating.

Archaeologists find an old bone. They want to know how old it is. They measure the Carbon-14 left in it. Since radioactive decay is basically "negative growth"—it shrinks based on how much is currently there—the math used to calculate the age is entirely dependent on log e.

Without this calculation, we wouldn't know if a mummy was from 3,000 years ago or last Tuesday.

It shows up in cooling, too. Newton’s Law of Cooling says that the rate at which your coffee gets cold is proportional to the difference between the coffee’s temp and the room’s temp. If you want to calculate exactly when your Starbucks will be drinkable without searing your tongue off, you’re using the natural log.

The Complexity of Sound and Sensation

Human perception isn't linear. It’s logarithmic.

If you are in a quiet room and someone drops a pin, you hear it. If you are at a rock concert and someone drops a pin, you don't. Your ears don't measure the absolute change in sound pressure; they measure the proportional change.

This is why we use decibels. It’s why we use the Richter scale for earthquakes. A magnitude 7 earthquake isn't "one more" than a magnitude 6. It’s about 10 times more powerful in terms of wave amplitude and about 32 times more energy release.

While common logs (base 10) are often used for these scales to keep the numbers pretty for humans, the underlying physics of how waves dissipate in the earth or air is almost always tied back to the natural log and $e$.

Common Misconceptions About Log e

People often think log e is just another button on the calculator to ignore. Or they get confused between $\log(x)$ and $\ln(x)$.

In most chemistry and physics textbooks, if you see "log" without a base, it might mean base 10. But in high-level math and pure science, "log" almost always defaults to base $e$. It’s that fundamental.

Another big mistake? Thinking $e$ is a variable. It’s not. It’s a constant. It never changes. It is as fixed as $\pi$.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you’re a student, stop trying to memorize the formulas. Instead, try to visualize what’s happening. Every time you see log e, just think: "How long did it take to grow this much?"

If you’re an investor, understand that compound interest is just a slow-motion version of $e$. The more frequently your interest compounds, the closer you get to that magic 2.718 ratio of growth.

Actionable Steps for Mastering the Concept

- Get a graphing calculator or use Desmos. Plot $y = e^x$ and $y = \ln(x)$. Look at how they are reflections of each other across a diagonal line. That’s the visual proof that the natural log is just the inverse of growth.

- Practice the conversion. Remember that $\ln(x) = y$ is just another way of saying $e^y = x$. If you can flip between those two in your head, you’ve won half the battle.

- Look for the "e" in nature. Next time you see the curve of a seashell or the way a plant's leaves are arranged, know that the math of log e is likely hidden in the growth patterns.

- Learn the derivative. If you're heading into calculus, remember that the derivative of $\ln(x)$ is $1/x$. It’s one of the cleanest, most beautiful transitions in mathematics, turning a weird transcendental curve into a simple fraction.

The natural logarithm isn't some torture device invented by mathematicians to ruin your GPA. It’s the language of everything that changes. From the way heat leaves a frying pan to the way a population of rabbits takes over a field, log e is the silent engine under the hood of the natural world. Once you see it, you can't un-see it.