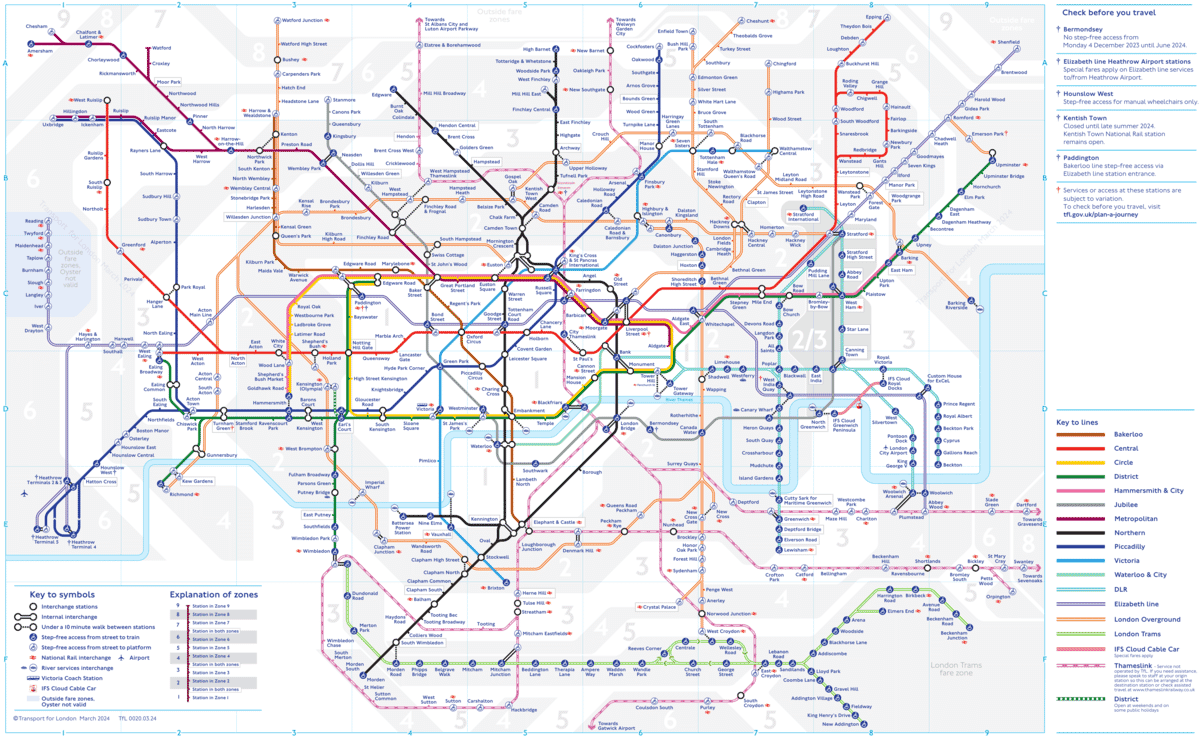

The London metro tube map is a lie. It’s a beautiful, iconic, globally recognized lie that keeps millions of people from getting lost every single year. If you look at the map and think you’re looking at a geographical representation of London, you’re basically trying to read a circuit board as if it were a photograph. It isn't.

It's a diagram.

Most people don't realize that the "map" they’re clutching on their phones or staring at on a windy platform at Elephant & Castle was never meant to show where things actually are on the ground. It was designed to solve a very specific problem: human panic. Back in the early 20th century, the actual geographic maps of the underground were a mess. Lines were clustered in the center and spindly at the edges. It looked like a plate of blue and red spaghetti that someone had dropped on a sidewalk. It was unreadable.

The Genius of Harry Beck's Radical Design

In 1931, an engineering draftsman named Harry Beck had a realization that changed how we see cities. He figured out that when you’re underground, you don’t care where you are in relation to the street above. You just want to know how to get from point A to point B and where to change trains. That’s it.

Beck was actually laid off from the London Underground Signals Office when he came up with the idea. He wasn't even a cartographer. He was an electrical draftsman, and that is exactly why the London metro tube map looks like a wiring diagram. He used only vertical, horizontal, and 45-degree diagonal lines. He spaced the stations out evenly, even though in reality, some stations are so close you could throw a stone between them while others are miles apart.

The authorities initially rejected it. They thought it was "too revolutionary." But they gave it a small trial run in 1933, and the public went nuts for it. It was a masterpiece of information design.

Honestly, the way Beck handled the central area—the "Bottle" or the "Circle Line"—is what makes it work. By expanding the center and compressing the outer reaches, he made the whole system look manageable. If you tried to draw the map to scale, the center of London would be a tiny black smudge of overlapping lines and the Metropolitan line would stretch off the paper into the next county.

Where the Map Actually Fails You

You've probably done it. Everyone has. You look at the map and see Leicester Square and Covent Garden. On the map, they look like they’re a decent distance apart, maybe a ten-minute walk or a quick hop on the Piccadilly line.

In reality? It's about 250 meters.

If you take the tube between those two stations, you’re spending more time on the escalator than in the tunnel. It is the most pointless journey in the entire network. But the London metro tube map makes it look like a necessary leg of a journey. This is the "Beck Effect." Because the map is topologically correct but geographically false, it distorts our perception of distance.

Take the walk between Mansion House and Cannon Street. On the map, they look like distinct stops on the District line. In the real world, you can literally see one station from the entrance of the other. The map encourages you to use the tube for trips that are faster on foot.

There is also the "South London Hole." If you look at the map, South London looks empty. It looks like a wasteland where the trains don't go. That isn't true at all. South London is packed with transport, but it’s mostly "National Rail" overground trains rather than the deep-level Underground. Because the map traditionally focused only on the TfL-run tube lines, it created a psychological divide in the city. If it isn't on the map, does it even exist? For many Londoners, the answer is a hard no.

The 2026 Reality: New Lines and Growing Pains

The map is getting crowded. Really crowded.

💡 You might also like: Why 10 Huntington Avenue Boston MA 02116 Still Dominates the Copley Square Scene

With the addition of the Elizabeth Line (the purple one that isn't technically a "tube" but everyone calls it that anyway) and the recent extensions of the Northern Line to Battersea Power Station, the elegance of Beck's original vision is being pushed to the breaking point. Adding more lines to a diagram that relies on simplicity is a nightmare.

You've got the Overground (the "Ginger Line"), the DLR, the Tramlink, and the cable car. Every time they add a new service, the font gets a little smaller. The lines get a little closer together. The "interchange" circles start to look like clusters of grapes.

There are serious debates among design geeks about whether the map needs a total reboot. Some people want to go back to something more geographic. Others think we should lean even harder into the diagram style. The problem is that the London metro tube map is more than a tool; it’s a brand. It’s on mugs, t-shirts, and duvet covers. You can’t just change the logo of a city without a riot.

Navigating the Map Like a Local

If you want to actually use the map effectively, you have to learn to read between the lines. Literally.

Look for the "walking links." Modern versions of the map sometimes include dotted lines showing where you can walk between stations in a few minutes. Use them. If you’re at Shepherd’s Bush on the Central Line and you need to get to the Overground, don't look for a tunnel connection that doesn't exist; just walk across the street.

Also, ignore the zones if you're just trying to find your way. The concentric circles of Zone 1, Zone 2, and so on are only there for your wallet. They tell you how much you're going to pay, not how long the trip will take.

- Check the line color first.

- Find your destination.

- Look for the "hollow" circles—those are your interchanges.

- Don't trust the distance between those circles.

The "Tube Map" isn't even the only map. There is a "Walking Tube Map" produced by TfL that shows how many steps are between stations. It’s a revelation. There is also a "Tunnel Map" that shows which stations have stairs vs. elevators (lifts), which is a lifesaver if you have luggage or a stroller.

The Psychological Grip of the Grid

Why do we love this map so much? Why did it become the template for almost every subway system in the world, from New York to Tokyo?

It’s because it provides a sense of order in a chaotic city. London is a mess of medieval streets and confusing alleys. The tube map is the only place where London feels organized. It’s a grid system imposed on a city that refuses to be a grid.

When you look at that map, you feel like you own the city. You see the connections. You see the possibilities. It doesn't matter that the distance between Paddington and Marylebone is totally misrepresented. What matters is that the map tells you that you can get there. It’s an optimistic document.

But remember: the map is not the territory. The map is a suggestion.

If you're stuck at a station because of "signal failures"—the classic London excuse—don't just stare at the map. Get out. Walk. You’ll realize that the city is much smaller and much more connected than those 45-degree angles lead you to believe.

Actionable Next Steps for Your Next Trip

- Download the "TfL Go" App: While the paper map is a classic, the official app uses a live version of the London metro tube map that adjusts for delays in real-time. It’s the most accurate way to see what's actually running.

- Check the Walking Maps: Before you tap your card for a one-stop journey, search for the "London Underground walking distance map" online. You’ll often find that walking from Charing Cross to Embankment is faster than waiting for the train.

- Look Up at the Platform: Every platform has a "strip map" for that specific line. It is much easier to read than the full "spaghetti" map when you’re already in the system.

- Visit the London Transport Museum: If you want to see Harry Beck’s original 1931 sketch (it’s on a page from a school exercise book), go to Covent Garden. It puts the whole evolution of the map into perspective.

- Memorize the "Interchange" Secret: Not all interchanges are created equal. Changing at Green Park is a long, soul-crushing walk through tunnels. Changing at Oxford Circus between the Victoria and Bakerloo lines is just a few steps across the same platform. Use the map to find the lines, but use your brain to find the "easy" switches.