Look at a globe. Seriously, just look at it. If you trace the giant landmass stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific, you won't see a natural break. There’s no massive ocean separating Paris from Beijing. Geographically speaking, we are looking at one singular slab of rock called Eurasia. Yet, for some reason, we’ve spent centuries obsessed with the map of Europe and Asia as if they were two different worlds. It’s a bit weird when you think about it. We’ve collectively agreed to draw a line through the middle of Russia and Turkey, deciding that one side is "Western" and the other is "Eastern," but the dirt under our feet doesn't really care about our labels.

Geography is often less about rocks and more about ego.

The traditional "border" is usually cited as the Ural Mountains. But have you ever seen the Urals? They aren't the Himalayas. They're old, weathered, and honestly, not that hard to cross. If you were standing in the middle of them, you wouldn't feel like you’d jumped into a different dimension. You’d just feel like you were on a big hill in Russia. This division is a human construct, born out of a desire by early European cartographers to distinguish themselves from the "Orient." It’s a messy, fascinating, and often politically charged way of looking at the world that still dictates how we teach history, run economies, and plan backpacking trips today.

Where Does Europe Actually End?

If you ask five different geographers where the boundary lies on a map of Europe and Asia, you might get six different answers. Most people go with the "Strahlenberg" line. Philip Johan von Strahlenberg was a Swedish officer and a prisoner of war who, back in 1730, suggested the Urals should be the limit. Before him, people thought the border was the Don River. Even earlier, the Greeks thought it was the Rioni River in Georgia.

The current "official" line—if there is such a thing—snakes down the Ural Mountains, follows the Ural River to the Caspian Sea, crosses the Caucasus Mountains, and then cuts through the Black Sea and the Bosphorus.

It’s complicated. Take Istanbul. You can literally take a ferry from Europe to Asia for the price of a coffee. One minute you're eating a croissant in a "European" cafe, and twenty minutes later, you're on the other side of the strait. It’s the same city. The same culture. The same people. But on a map, they are on two different continents. Russia is even crazier. About 75% of its land is in Asia, but 75% of its people live in Europe. It’s a geopolitical identity crisis that has lasted for hundreds of years.

The Problem With the "Continent" Definition

We were all taught in grade school that a continent is a large landmass separated by water. North America and South America? Linked by a tiny strip, but okay. Africa? Surrounded by ocean mostly. Antarctica? Isolated. Then you get to the map of Europe and Asia and the whole definition falls apart.

🔗 Read more: Dominican Republic: Why You’ve Probably Been Doing It All Wrong

There is no water separation.

Tectonically, they sit on the same plate (the Eurasian Plate). If we were being scientifically honest, we’d call it one continent. But humans love categories. We like to put things in boxes. Europe, for a long time, wanted to see itself as a distinct cultural entity—the "Old World"—separate from the vastness of the East. This wasn't based on tectonic plates; it was based on religion, politics, and trade routes.

Some geographers, like those at the National Geographic Society, acknowledge that the division is purely cultural. They use the term "Eurasia" to describe the physical reality. However, try telling a tourist in Rome they are in "Western Eurasia" instead of Europe. It just doesn't have the same ring to it.

The Transcontinental Countries: Living on Both Sides

There are a handful of countries that refuse to pick a side. They are the "transcontinental" nations. Russia and Turkey are the famous ones, but they aren't alone.

- Kazakhstan: Most people think of it as Central Asian, but a small slice of its western territory sits west of the Ural River, making it technically part of Europe.

- Georgia and Azerbaijan: These sit right on the spine of the Caucasus. Depending on which map you look at, they are either in Europe, Asia, or a confusing "in-between" zone.

- Greece: While firmly European, some of its islands are just a stone's throw from the Turkish coast.

This creates some hilarious situations in the world of sports. For example, why does Israel or Kazakhstan play in the UEFA European Championship? Because "Europe" in the modern world is more of a club you join than a place you inhabit. It's an idea. It's a set of trade agreements, sports leagues, and political alliances. When you look at a map of Europe and Asia, you’re looking at a history of who wanted to be friends with whom.

Why the Urals Don't Really Work

If you look at the Ural Mountains on a topographical map, they look like a skinny green zipper running north to south. They aren't a massive barrier. Throughout history, nomadic tribes, traders, and armies have moved across them with relative ease. The Huns didn't care about the Urals. The Mongols certainly didn't.

The idea that this specific mountain range is a "continental divide" was basically a marketing move by the Russian Empire. Peter the Great wanted Russia to be seen as a European power. By pushing the "border" of Europe all the way to the Urals, he could claim that the heart of his empire was European. It was a way to pivot away from the Golden Horde's legacy and toward the enlightenment of Paris and London.

The Caucasus: The Other Messy Border

The southern border is even more debated. Does the line follow the watershed of the Caucasus Mountains, or does it follow the Kuma-Manych Depression to the north?

If you use the mountain peaks, then Mount Elbrus is the highest mountain in Europe. If you use the depression further north, then Mont Blanc in the Alps takes the title. This matters deeply to mountaineers who want to climb the "Seven Summits." If you're a climber, the map of Europe and Asia you choose determines whether you’re heading to Russia or France for your trophy.

Most modern mappers lean toward the watershed line. This puts the northern parts of Georgia and Azerbaijan in Europe. But go to Baku or Tbilisi and ask the locals. They’ll tell you they feel like a bridge between cultures. They have the ancient wine traditions of the West and the silk-road hospitality of the East. They are living proof that maps are just suggestions.

Cultural vs. Physical Maps

We tend to think of maps as objective truths. They aren't. A map of Europe and Asia is a snapshot of how we perceive power. During the Cold War, the "map" changed. Eastern Europe wasn't just a place; it was a political designation. Countries like Poland or Hungary were lumped into "the East," even though they are geographically more central.

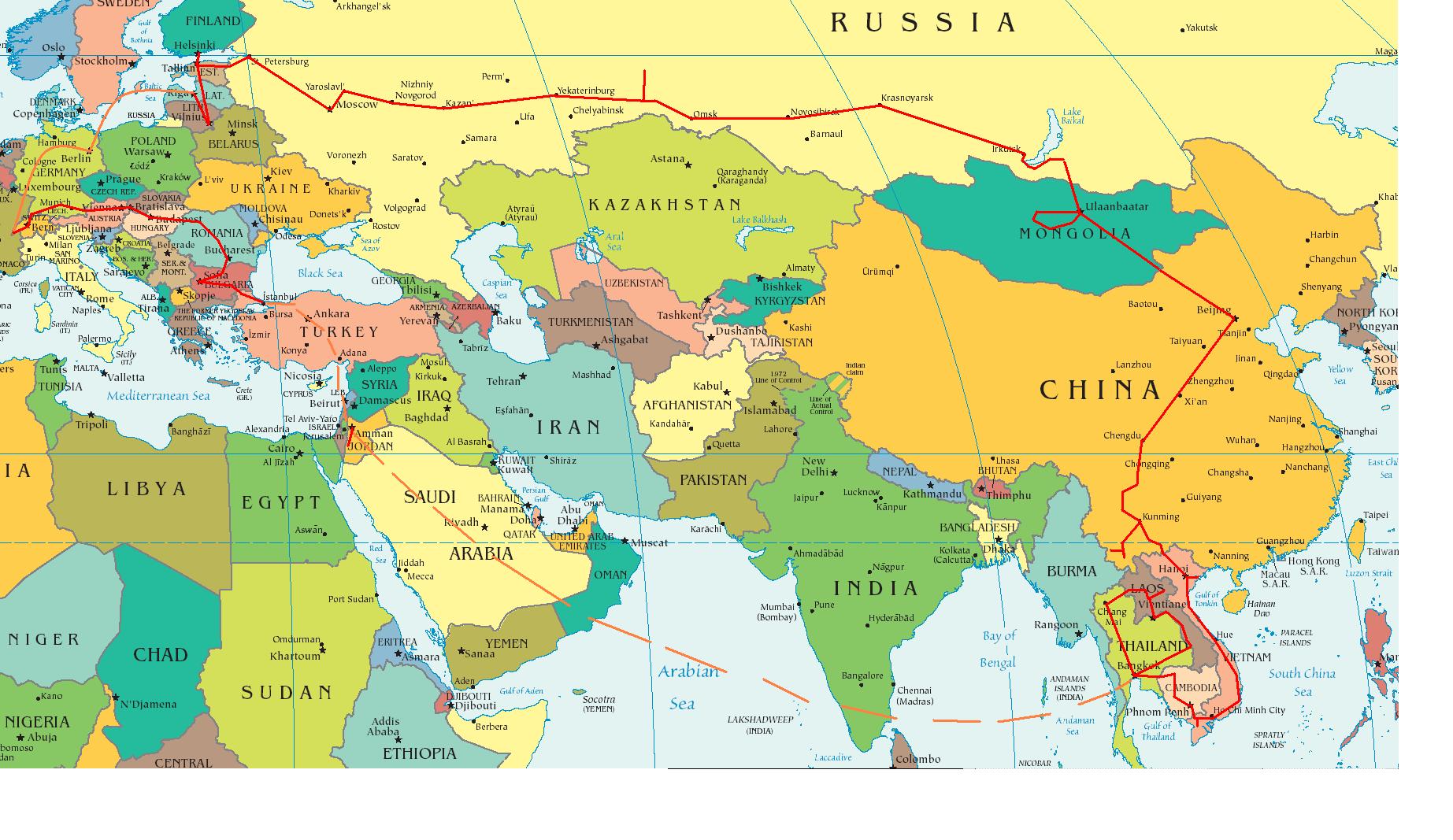

Now, we see the rise of the "Indo-Pacific" and "Eurasianism." These are new ways of drawing the map that ignore the 18th-century European borders. China’s "Belt and Road Initiative" is essentially an attempt to redraw the map by building trains and pipelines that ignore the Ural "border" entirely. They are treating Eurasia as a single economic unit, which, frankly, it is.

What This Means for You (The Actionable Part)

If you’re traveling, studying, or just curious about the world, stop looking for the "seam." It doesn't exist. Instead, lean into the blur.

1. Visit the "Middle"

Don't just go to London or Tokyo. Go to the places that break the map. Visit Istanbul and cross the Bosphorus. Go to Tbilisi and see the mix of Orthodox cathedrals and Persian-style baths. Visit Yekaterinburg in Russia, where there is literally a monument marking the spot where Europe ends and Asia begins. Standing with one foot in each "continent" is a great way to realize how silly the distinction is.

2. Check Your Sources

When you see a statistic about "European GDP" or "Asian population," look at the fine print. Does it include Russia? Does it include Turkey? Data scientists and economists move these borders around all the time to suit their narrative. Always ask: "Which map are they using?"

3. Embrace Eurasia

Start thinking of it as one big playground. The most interesting parts of the world are the transition zones. The places where the food, language, and architecture are a messy, beautiful hybrid. The Silk Road wasn't a bridge between two worlds; it was the nervous system of a single one.

4. Study the Tectonics

If you want the real truth, look at a geological map. Forget the countries. Look at the plates. You'll see that India is actually more "separate" from Asia than Europe is. India is crashing into Asia, creating the Himalayas. Europe is just... there. It’s been part of the family for a long time.

At the end of the day, a map of Europe and Asia is a tool. It helps us organize our world, but it shouldn't limit how we see it. The border is a ghost. It’s a line drawn in ink by people who have been dead for three hundred years. Once you realize the border is imaginary, the whole world starts to look a lot more connected.

Go look at that globe again. See the land? It’s all one piece. The rest is just us talking.