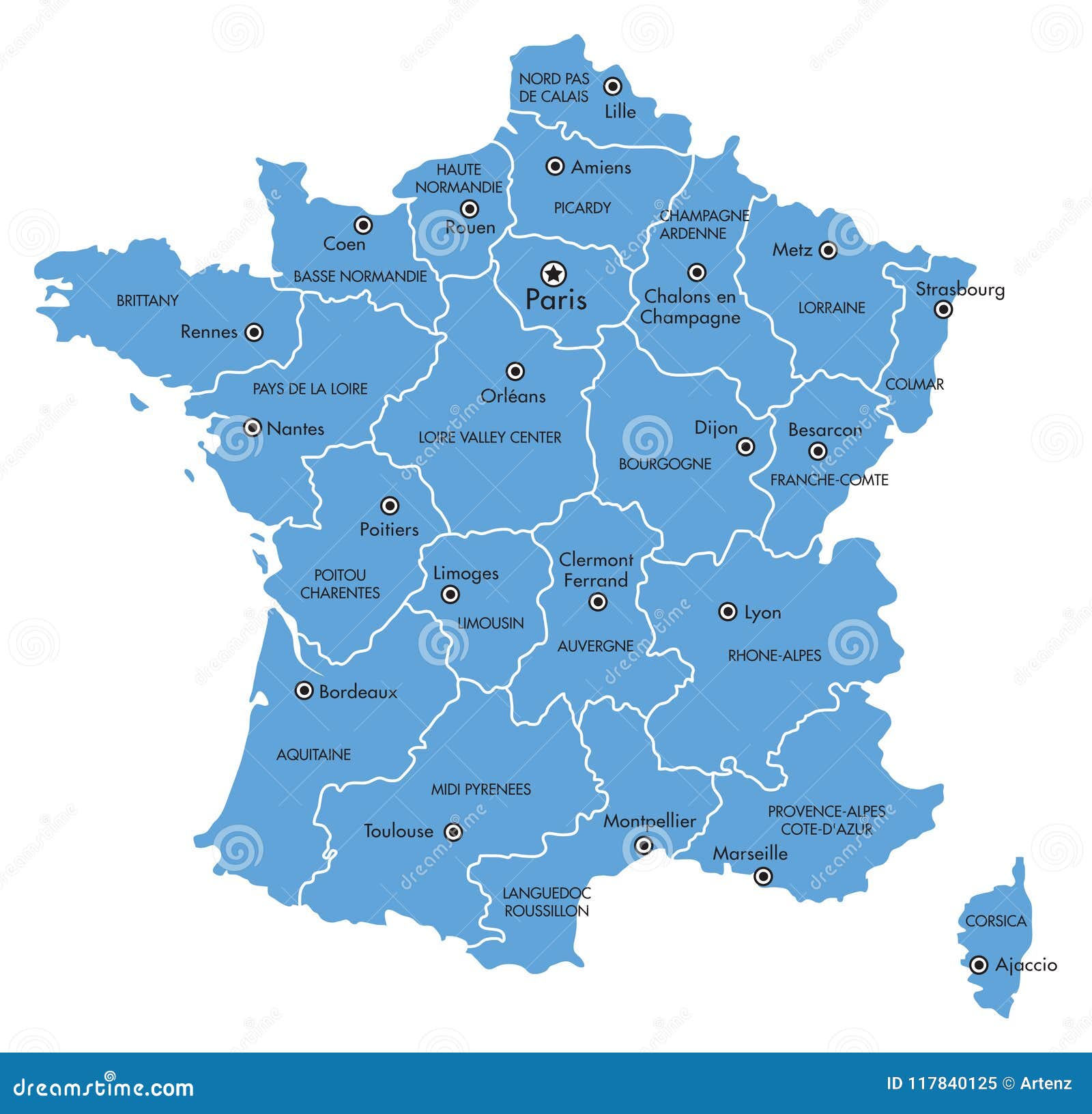

France is a mess. Or, at least, its borders used to be. If you’ve ever stared at a map of france provinces and felt like you were looking at a shattered stained-glass window, you’re not alone. Most people confuse the old historical provinces with the modern administrative regions, and honestly, even the French get it mixed up sometimes.

History is messy. While the French Revolution tried to wipe the slate clean in 1790 by carving the country into logical, numbered departments, the ghost of the old provinces never really left. People still say they are from "Brittany" or "Gascony," even if those names haven't officially designated a government territory in over two centuries.

It’s about identity. You can’t just erase a thousand years of feuding dukes and distinct dialects with a pen and a compass. Understanding the map means realizing that France wasn't built; it was assembled, piece by piece, often through messy marriages or bloody sieges.

The 1789 Problem: Why the Map Changed

The National Constituent Assembly had a massive headache in 1789. The old provinces were a nightmare of overlapping jurisdictions. Some were huge, like the Duchy of Brittany, and others were tiny pockets of land owned by random nobles. Taxes were different everywhere. Laws were different everywhere. It was a logistical disaster for a new republic that wanted equality.

📖 Related: Getting Your Bearings: Why the Map of Egypt and the Red Sea is Weirder Than You Think

So, they killed the provinces.

They replaced them with Departments. The idea was brilliant in its simplicity: every citizen should be able to reach their department’s capital city within a single day’s ride on horseback. This led to about 83 original departments (now 101), which were intentionally named after rivers or mountains rather than historical titles. They wanted to kill the idea of "Burgundy" or "Normandy" to prevent people from being loyal to a local Duke instead of the nation.

It didn't totally work. While the administrative map changed, the cultural map stayed exactly where it was.

The Heavy Hitters: Normandy and Brittany

When you look at a map of france provinces from the Ancien Régime, two shapes on the northwest coast always stand out. Normandy is basically the cradle of modern English and French history. It was handed over to the Viking leader Rollo in 911 because the French King was tired of getting raided. That "Norseman's Land" eventually became the launchpad for William the Conqueror. Even today, the distinction between Upper Normandy (centered on Rouen) and Lower Normandy (Caen) is a point of local pride that survives the bureaucratic shuffling.

Then there's Brittany. It’s the rugged, granite-edged peninsula that feels more Celtic than French. For a long time, it was an independent duchy. It only became part of France because of a series of strategic marriages involving Anne of Brittany. If you visit today, you’ll see the Breton flag everywhere—black and white stripes and ermine spots—proving that a provincial map from 1500 is still more relevant to the locals than a modern postal code.

The "Sun King" Expansion: Alsace and Lorraine

The eastern border of France is where things get really complicated. If you look at the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, you’re looking at a centuries-long tug-of-war between France and the various Germanic powers. Louis XIV, the famous "Sun King," was obsessed with pushing France to its "natural borders," specifically the Rhine River.

Alsace is a weird one. It’s got half-timbered houses and a dialect that sounds much more like German than the French you'd hear in Paris. When the provinces were abolished, Alsace was split into the departments of Haut-Rhin and Bas-Rhin. But the cultural memory of the province is so strong that in 2021, France actually created the "European Collectivity of Alsace," basically admitting that these two departments are, and always will be, one single cultural unit.

Why Occitania Matters

The south of France is a different world. Historically, the southern half of the map of france provinces was known as Occitania. They didn't even speak the same language as the northerners. In the north, they said "oil" for yes; in the south, they said "oc." This linguistic divide (the Langue d'Oc) defined a massive area including provinces like Languedoc, Provence, and Gascony.

Gascony is particularly cool. It's the home of d'Artagnan from The Three Musketeers. It wasn't just a fictional setting; it was a rough, frontier-like province known for producing fierce soldiers and incredible brandy. Today, Gascony doesn't exist on a modern political map, but go to a market in the Gers department and try telling someone they aren't Gascon. You’ll get a very quick history lesson.

The Heart of the Matter: Île-de-France

Right in the middle is the Île-de-France. It means "Island of France," which sounds weird because it’s nowhere near the ocean. It was called that because it was the small pocket of land surrounded by rivers (the Seine, Marne, and Oise) that the early French kings actually controlled.

Back in the 10th century, the "King of France" was basically just the "Mayor of Paris." The rest of the provinces—Aquitaine, Champagne, Burgundy—were often more powerful than the King himself. The history of the French map is essentially the story of the Île-de-France slowly swallowing its neighbors until the whole thing turned blue on a map.

The Great 2016 Region Shake-up

To make things even more confusing for travelers, the French government did a massive "merger" in 2016. They took the 22 modern administrative regions and condensed them into 13. This was done to save money and create "super-regions" that could compete with German states.

- Aquitaine, Limousin, and Poitou-Charentes became Nouvelle-Aquitaine.

- Midi-Pyrénées and Languedoc-Roussillon became Occitanie.

- Champagne-Ardenne, Lorraine, and Alsace became Grand Est.

While this was great for the budget, it was a nightmare for regional identity. People in Alsace were furious about being lumped into "Grand Est" (which literally just means "Great East"). It felt clinical. It felt like the map-makers were ignoring the centuries of provincial history that made these places unique in the first place.

How to Use This Knowledge

If you’re planning a trip or researching history, stop looking for one "correct" map. There isn't one. Instead, you have to layer them.

The provincial map (pre-1789) tells you about the food, the architecture, and the soul of the place. If you want to know why people eat butter in the north and olive oil in the south, look at the provinces. If you want to know why the houses in the Dordogne look like golden stone castles, look at the history of the Périgord province.

The departmental map (post-1789) is what you use for GPS and mail. It’s the two-digit code at the start of a French zip code or at the end of a license plate. "75" is Paris. "13" is Marseille. It’s efficient, but it’s dry.

The regional map (post-2016) is what you use for train tickets and major government projects.

Actionable Insights for Map Enthusiasts

- Check the Wine Labels: French wine is almost always categorized by provincial logic, not modern administrative lines. A "Bordeaux" comes from the old province of Aquitaine, specifically the area around the Gironde.

- Look at License Plates: In France, the right-hand side of a license plate shows a department number and a regional logo. It’s a fun game to see how many people choose to display a logo for a region they don't even live in, just because they identify with their ancestral province.

- Search by "Pays": If you’re traveling, look for the "Pays" (country/land). Terms like Pays Basque or Pays de la Loire will give you much better cultural results than searching for modern administrative districts.

- Respect the Borders: Don't tell someone from Savoy (Savoie) that they are just "Eastern French." Savoy didn't even become part of France until 1860. They have their own cross-shaped flag and a very distinct mountain culture that predates their inclusion in the republic.

The map of France isn't a static image. It’s a living document of conquests, marriages, and revolutionary stubbornness. Whether you're looking at the aristocratic sprawl of the Anjou or the rugged mountains of Auvergne, you're seeing the fingerprints of people who refused to be just another number on a bureaucrat’s desk. Use the old names. Explore the old borders. That’s where the real France is hiding.