You can't see it. You can't feel it. But every single thing you touch, from the screen you're scrolling on to the coffee mug sitting on your desk, is basically just a collection of these impossibly small dots. When we talk about the mass of an electron kg, we aren't just talking about a boring homework assignment for a physics 101 class. We're talking about the fundamental building block of literally everything.

It’s small. Mind-bogglingly small.

If you try to weigh an electron on a kitchen scale, nothing happens. Obviously. To get a real sense of the scale, imagine if a single paperclip was the size of the entire Milky Way galaxy. In that scenario, an electron would still be smaller than a grain of sand. We are dealing with levels of "tiny" that the human brain isn't even wired to understand. Honestly, it’s a miracle we managed to measure it at all.

The Number That Changed Physics

So, let's get the big number out of the way. The accepted value for the mass of an electron kg is approximately $9.1093837 \times 10^{-31}$ kilograms.

Look at that exponent. Negative thirty-one. That means you take a 9, put a decimal point in front of it, and then shove thirty zeros between the point and the number. It's essentially zero, but that "essentially" is doing a lot of heavy lifting. If that number were even slightly different—if it were a tiny bit heavier or lighter—the universe wouldn't work. Atoms wouldn't hold together. Chemistry wouldn't exist. You wouldn't exist. It's one of those universal constants that feels like the fine-tuning of a cosmic engine.

Scientists didn't just wake up one day and know this. It took decades of arguing, messy experiments, and a guy named J.J. Thomson messing around with "cathode rays" in 1897 to realize that atoms weren't the smallest thing out there. He discovered the electron, though he didn't quite get the mass right at first. He just knew it was much, much lighter than a hydrogen atom.

How do you weigh something you can't see?

You don't use a scale. You use magnetism and electricity.

Think about it like this: if you're standing outside and a tiny pebble flies past you, you can swat it away easily. If a bowling ball flies past you at the same speed, you're going to need a lot more force to change its direction. Physicists did the same thing with electrons. They fired them through magnetic and electric fields and watched how much they curved.

👉 See also: Update Firmware for LG TV: Why Your Screen Is Acting Up and How to Fix It

Since they knew how much "push" (force) they were applying, and they could see how much the electron "swerved" (acceleration), they could calculate the mass. It's basically Newton's second law, $F = ma$, just applied to things so small they behave like waves half the time. Robert Millikan famously refined this with his oil-drop experiment in 1909. He literally suspended tiny droplets of oil in mid-air using electrical tension to figure out the charge of a single electron, which eventually led us to the precise mass we use today.

Why mass of an electron kg matters for your gadgets

Why should you care about a number with thirty zeros? Because your smartphone is a literal electron manipulator.

Semiconductors work because we understand exactly how much energy it takes to move an electron from one place to another. If the mass of an electron kg was different, the way electrons flow through silicon would change. Your processor would overheat instantly, or the electrical signals wouldn't move fast enough to process a single line of code.

Everything in modern technology—from the LED lights in your house to the "quantum dots" in your high-end TV—relies on the specific mass and charge of these particles. We've spent the last century learning how to dance with these tiny specks.

The Electron vs. The Proton

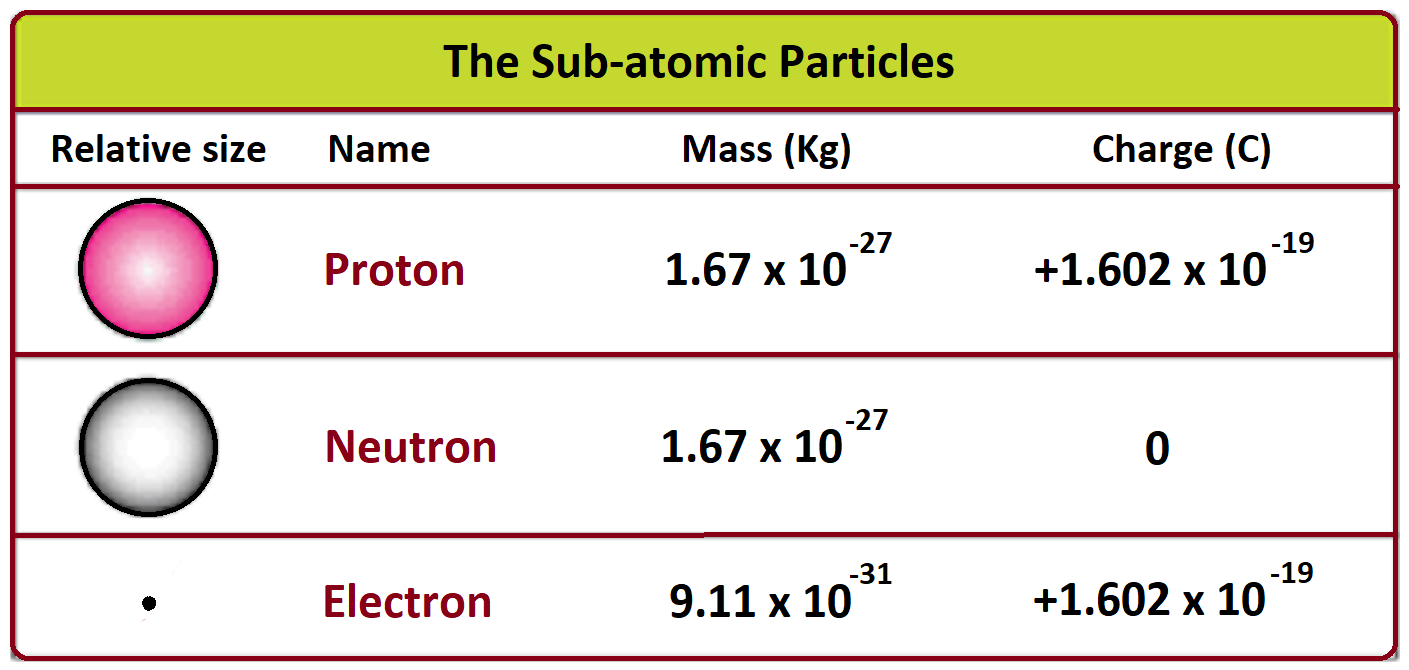

It’s a bit of a lopsided relationship. A proton is about 1,836 times heavier than an electron.

If a proton was a 180-pound man, an electron would be the weight of a small candy bar in his pocket. This mass difference is why electrons are the ones that do all the moving. Protons stay hunkered down in the nucleus like the heavy foundation of a house, while electrons zip around the outside, jumping from atom to atom, creating chemical bonds and electrical currents.

📖 Related: Is Silicon Valley in San Francisco? What Most People Get Wrong

This mobility is what makes life possible. When your neurons fire to read this sentence, it’s a shift in ions, driven by the nimble, low-mass nature of electrons. They are the "light infantry" of the universe, able to pivot and react at speeds that heavier particles just can't match.

Misconceptions about "Mass" at this Scale

Here is where things get kinda weird. When we talk about the mass of an electron kg, we're usually talking about its "rest mass."

In the world of Einstein, mass and energy are two sides of the same coin ($E = mc^2$). When an electron starts moving really fast—like, close to the speed of light—it starts acting heavier. This is called relativistic mass. In particle accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), electrons can be pushed to energies where they "weigh" much more than their rest mass.

- Wait, is it a particle or a wave? It's both. This is the "quantum headache" physicists have been dealing with for a hundred years.

- Does it have a size? Actually, as far as we can tell, the electron is a "point particle." That means it has no physical volume. It has mass, it has charge, but it doesn't take up "space" in the way a marble does.

- Can we split it? Nope. Unlike protons and neutrons, which are made of even smaller things called quarks, the electron is an elementary particle. It's the end of the line.

Measuring the Impossible: The NIST Standards

We don't just guess these numbers. Organizations like the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the CODATA Task Group on Fundamental Constants spend years refining these measurements.

They use something called a Penning trap, which uses a combination of magnetic and electric fields to hold a single electron (or a single ion) in place. By measuring the "cyclotron frequency"—how fast it circles in the trap—they can calculate the mass with incredible precision. In 2026, our measurements are so precise that we're looking at uncertainties of only a few parts per billion.

That level of accuracy isn't just for bragging rights. It's necessary for things like GPS, which requires incredibly precise timing and understanding of subatomic interactions to keep your blue dot on the map from drifting into a lake.

The "Rest" of the Story

Sometimes you’ll see the electron’s mass expressed in "u" (atomic mass units) or in energy terms like MeV ($0.511\text{ MeV}/c^2$). Physicists love to do this because it makes the math easier. Writing out $9.11 \times 10^{-31}$ every time is a great way to get a carpal tunnel.

But staying in kilograms keeps us grounded. It reminds us that no matter how ghostly and "wave-like" an electron seems, it is a physical piece of the universe. It has inertia. It resists movement. It is stuff.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you're a student, a tech enthusiast, or just someone who likes knowing how the engine of the universe runs, don't just memorize the number. Understand the implications.

- Check the constants: If you're doing physics or chemistry work, always use the most recent CODATA value for mass of an electron kg. It's updated periodically as measurement technology improves.

- Think in Ratios: Remember the 1/1836 ratio between electrons and protons. It’s the most helpful way to visualize why electrons are the "workers" of the atomic world.

- Explore Quantum Mechanics: If the idea of a mass with no volume bothers you (it should!), look into the Schrödinger equation. It explains how that mass is distributed as a "probability cloud" rather than a hard shell.

- Observe the Tech: Next time you use a device with a battery, realize you are literally moving a specific mass of electrons from an anode to a cathode. You are a mass-mover on a subatomic scale.

The universe is built on these tiny, specific foundations. The mass of an electron kg might be a small number, but it’s the pivot point for everything we know about reality. Without that precise $10^{-31}$ kilogram weight, the stars wouldn't shine, and we wouldn't be here to wonder why.