Mathematics is basically a language that nobody actually speaks out loud. When you look at a page of calculus or even just a complex interest rate formula, you aren't looking at numbers so much as you're looking at shorthand. It's a code. Honestly, if we had to write out "the square root of the sum of these two numbers squared" every single time we wanted to do math, we’d still be stuck in the Middle Ages trying to build a basic bridge. Mathematical symbols are the ultimate productivity hack of human history.

Most people think these marks were handed down from some ancient mountain by a guy in a toga. That's not really how it happened. Symbols like the plus sign or the equals sign are actually quite young in the grand scheme of things. They evolved through messy arguments, handwriting shortcuts, and printers getting annoyed with having to carve new woodblocks for every book.

🔗 Read more: How to Delete a Hulu Profile: What Most People Get Wrong

The Drama Behind the Equals Sign

Robert Recorde was a Welsh physician and mathematician in the 1500s who got tired of writing "is equal to" over and over again. In his book The Whetstone of Witte, he decided to use two parallel lines because, in his words, "noe 2 thynges can be moare equalle."

It’s kind of funny that the most iconic symbol in the world was born out of one guy's pure laziness. Before Recorde, people used the word est or even strange abbreviations like ae. Some mathematicians even used a vertical line. But the horizontal parallel lines won because they were visually intuitive. You see them and you instantly get it. Balance.

The Plus and Minus Evolution

We take $+$ and $-$ for granted. But for a long time, the plus sign was just the Latin word et, which means "and." If you write et fast enough in cursive, the "t" starts to look like a cross. By the 1480s, German mathematicians were using it as a mark to show that a crate of goods was overweight. It wasn't even a math thing at first; it was a shipping thing.

The minus sign is even weirder. It might have come from a bar used by merchants to show a crate was underweight, or it could be a shorthand for the letter m. Some historians think it’s just a simplified version of the Egyptian hieroglyph for walking backward. Regardless of where it came from, it’s arguably the most minimalist tool in our toolkit.

Beyond Arithmetic: The Symbols That Scare People

Once you get past basic addition and subtraction, mathematical symbols start looking like a different alphabet. Because they are. We use Greek letters for a reason.

Take $\pi$ (Pi). We all know it’s $3.14$ and change. But using the Greek letter wasn't standard until Leonhard Euler started using it in the 1700s. It stands for perimetros, the Greek word for perimeter. It’s a ratio. If you have a circle, no matter how big or small, the distance around it is always about $3.14$ times the distance across it. It’s a universal constant. It’s weirdly beautiful when you think about it.

Then you have the Sigma $\sum$ and the Integral $\int$.

💡 You might also like: Set iPhone to Do Not Disturb: Why Your Notifications Are Still Breaking Through

The $\sum$ is just a fancy Greek 'S' for "sum." If you see a Sigma, it’s just a giant "Add everything up!" command. The Integral symbol, that long skinny 'S', was actually created by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. He based it on the word summa. He and Isaac Newton famously fought over who invented calculus, but Leibniz definitely won the branding war because his symbols are the ones we still use today.

Set Theory and Logic: The Modern Code

If you’ve ever looked at a logic proof and seen $\forall$ or $\exists$, you’ve entered the world of formal logic.

- $\forall$ means "for all." It’s literally just an upside-down 'A'.

- $\exists$ means "there exists." It’s a backwards 'E'.

Giuseppe Peano, a 19th-century Italian mathematician, was the mastermind behind a lot of this. He wanted to strip away the ambiguity of human language. Words like "some" or "every" can be slippery. Symbols are rigid. They don’t lie. When a programmer writes code today, they are standing on the shoulders of Peano’s obsession with clarity.

The Square Root and the Power of Shorthand

The $\sqrt{}$ symbol is called a radical. Most scholars believe it’s a deformed 'r', which stands for radix, the Latin word for root. Imagine a medieval monk scribbling 'r' so fast that the tail of the letter dragged across the top of the number. That’s how we got the vinculum (the horizontal line over the number).

Without these shortcuts, modern physics would be impossible. Imagine trying to write the Theory of Relativity using only sentences. It would take ten pages. Instead, we have $E=mc^2$. That tiny '2' in the corner—the exponent—was popularized by René Descartes. Before him, people wrote $xxx$ for $x$ cubed. It was messy. It was cluttered. Descartes realized that height could represent power.

Why We Still Use Greek Letters

You might wonder why we don't just use modern English letters for everything. It’s partly tradition, but it’s mostly about avoiding confusion. If you use 'a' for acceleration and 'a' for an angle, your math breaks.

By pulling from the Greek alphabet—using $\theta$ (theta) for angles or $\lambda$ (lambda) for wavelengths—mathematicians created a "reserved" set of characters. It’s like having a specialized keyboard for the universe.

📖 Related: Photoshop How to Remove a Person: Why Your Edits Look Fake and How to Fix Them

- $\Delta$ (Delta) usually means change.

- $\infty$ (Infinity) isn't a number; it's a concept of "no end."

- $\approx$ means "close enough" or approximately equal.

Common Misconceptions

People often think math symbols are static. They aren't. They shift. In some parts of Europe, a comma is used as a decimal point. In the US, it’s a period. This actually causes real-world problems in engineering and finance.

Another big one: the multiplication sign. You've got the 'x', the dot $\cdot$, and the asterisk $*$. We use the dot or parentheses in algebra because an 'x' looks too much like the variable $x$. It’s all about visual hygiene.

Moving Forward With This Knowledge

Understanding mathematical symbols isn't about memorizing a dictionary. It's about recognizing patterns. When you see a symbol you don't recognize, don't panic. It's usually just a shorthand for a very simple concept that would be too long to write out.

To actually get better at this, start by "translating" formulas back into plain English. If you see $A = \pi r^2$, say to yourself: "The Area is equal to Pi times the radius, and that radius is multiplied by itself."

Once you start reading the symbols as words, the fear goes away. You aren't doing "math" anymore; you're just reading a very condensed story about how the world works.

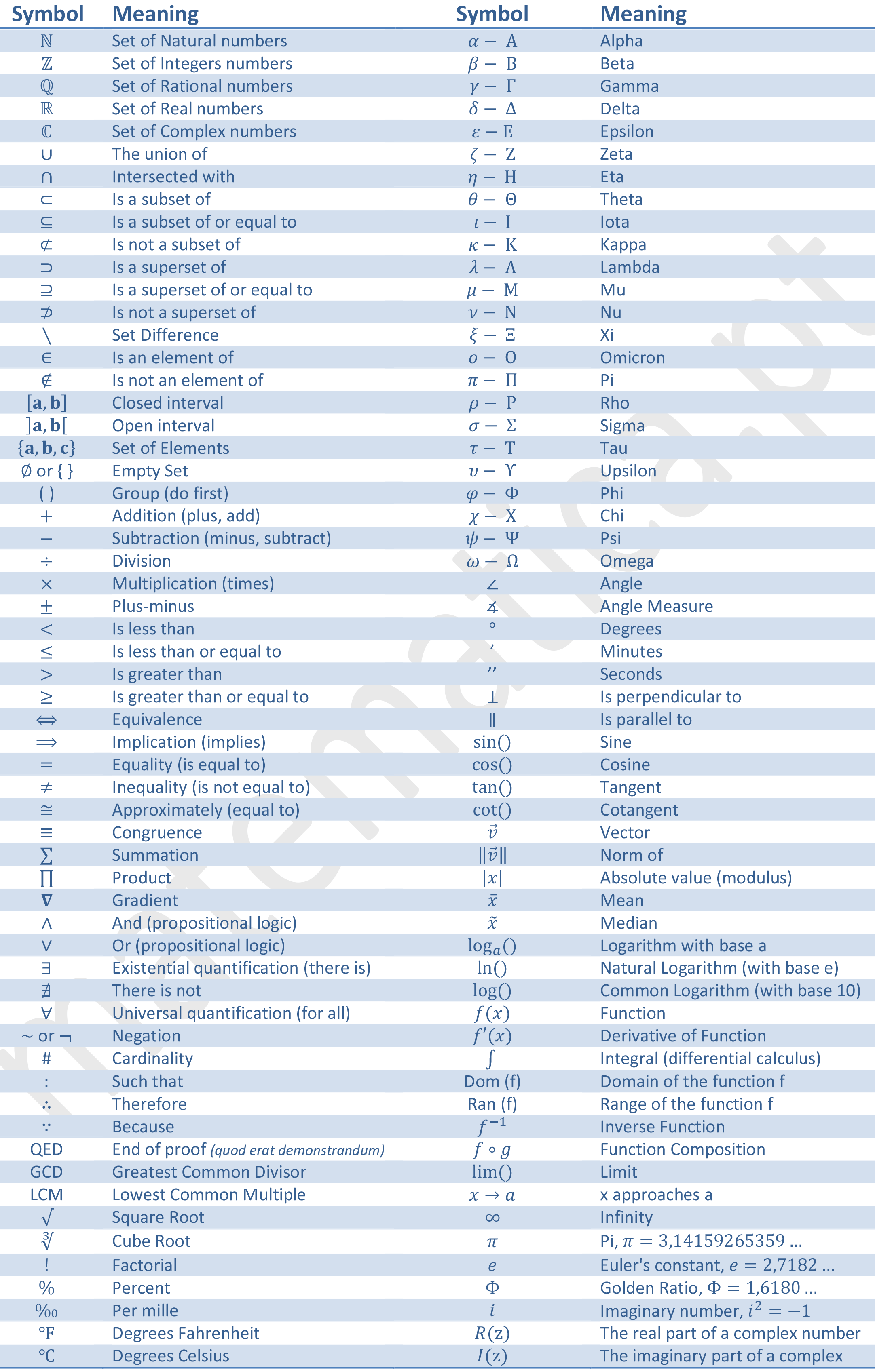

If you're looking to dive deeper into technical notation, your next best move is to look up a "Table of Mathematical Symbols" on Wikipedia or Wolfram MathWorld. Keep it open as a reference sheet. Over time, you’ll stop looking at the sheet and just start seeing the logic. Mathematics is the only language where everyone across the globe agrees on the grammar. That’s pretty rare.