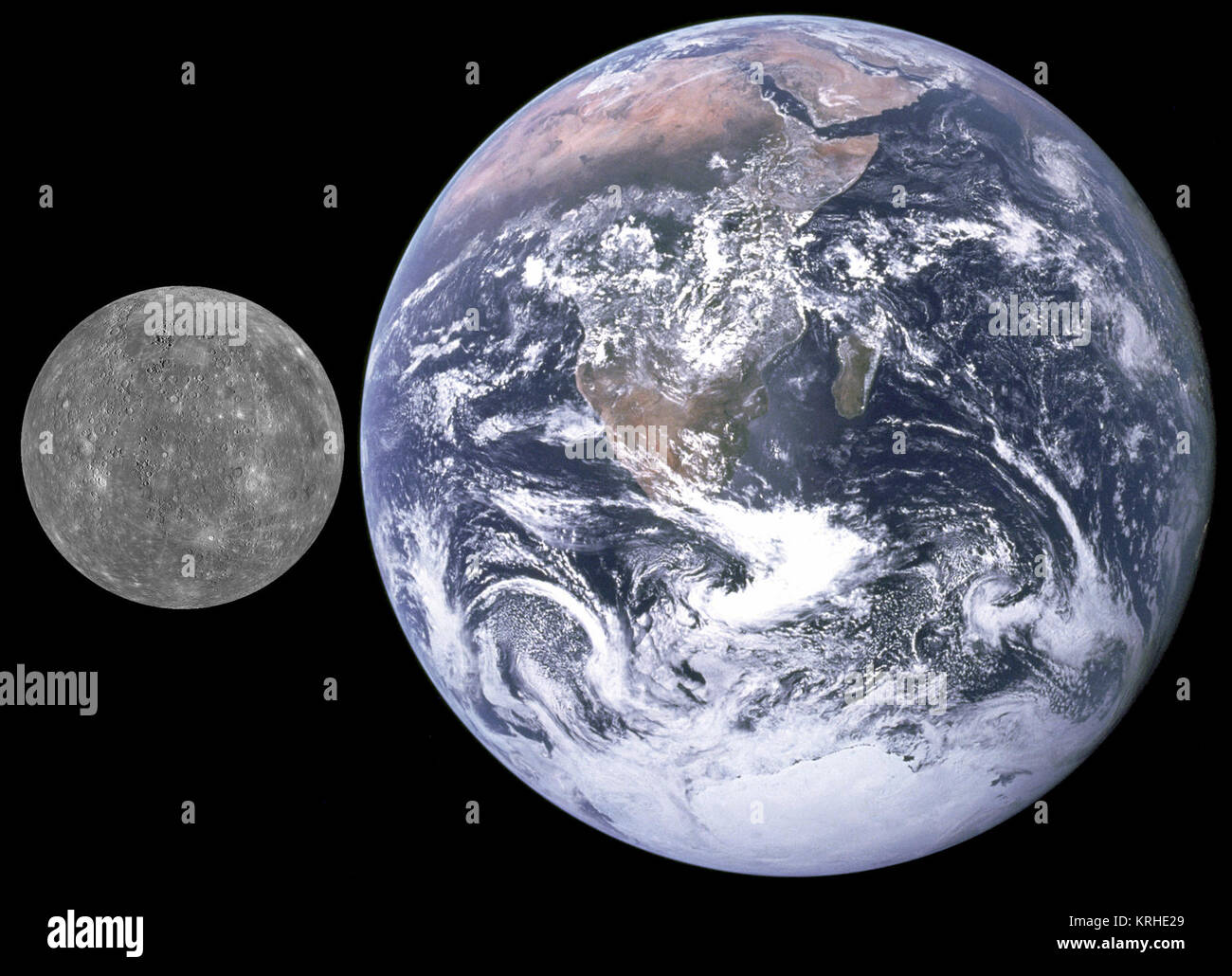

It is tiny. If you took Earth and shrunk it down to the size of a basketball, Mercury would be roughly the size of a tennis ball or even a large plum. When we talk about Mercury size, we aren't just talking about a small planet; we are talking about a world that barely managed to graduate from being a moon. In fact, it's actually smaller than Ganymede (Jupiter's moon) and Titan (Saturn's moon). That is wild. A whole planet, orbiting the Sun, yet physically smaller than two moons belonging to its gas giant neighbors.

Honestly, looking at Mercury through a telescope or in NASA's Messenger mission photos, you’d be forgiven for thinking you’re looking at our own Moon. It's gray, cratered, and seemingly dead. But the size of Mercury tells a story of a planet that is far more dense and "metallic" than it has any right to be.

The Raw Numbers: Mercury Size by the Megameter

Let's get the math out of the way. Mercury has a radius of about 1,516 miles (2,440 kilometers). If you want to talk diameter, we are looking at roughly 3,032 miles across. To put that in perspective, the United States is about 2,800 miles wide from coast to coast. You could basically roll Mercury across the North American continent, and it would almost fit between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

It is small.

But here is where it gets weird. Even though Mercury is only about 38% the diameter of Earth, it is incredibly heavy for its size. This is because Mercury is basically a giant ball of iron with a thin wrapper of rock around it. Unlike Earth, which has a relatively balanced core-to-mantle ratio, Mercury’s core takes up a massive 85% of its radius. Imagine a cherry where the pit is almost the size of the entire fruit, and the skin and flesh are just a thin layer on the outside. That is Mercury.

Mass vs. Volume

Volume-wise, you could fit about 18 Mercurys inside Earth. If you had a giant bucket the size of our world, you’d be dumping Mercury after Mercury into it before it finally overflowed. Yet, because it’s so dense, its gravity is 38% of Earth’s. If you weigh 200 pounds here, you’d weigh about 76 pounds on Mercury. You could dunk like Michael Jordan without trying, though the lack of an atmosphere and the 800-degree heat might make the game a bit uncomfortable.

Why Mercury Size Matters for its Survival

Why did it end up so small? Astronomers have been arguing about this for decades. One leading theory suggests that in the early, chaotic days of the solar system, a massive "protoplanet" (a planet embryo) slammed into Mercury. This cosmic hit-and-run might have stripped away most of its lighter, rocky outer crust, leaving behind the heavy metallic core we see today.

Another idea is that being so close to the Sun—only about 36 million miles away—the intense heat and solar wind simply blasted away the lighter materials before they could settle. It’s like Mercury was a bigger snowball that got too close to the fire and partially melted away.

Regardless of the "how," the Mercury size we see today is a survivor's size.

The Shrinking Planet

Here is a fact that sounds fake but is 100% real: Mercury is actually getting smaller. As that massive iron core slowly cools, it solidifies. When things solidify and cool, they often contract. Because the planet is shrinking, its outer crust is literally wrinkling like a raisin.

Geologists call these wrinkles "lobate scarps." These are massive cliffs, some hundreds of miles long and over a mile high. They are essentially giant thrust faults where the ground has buckled because the interior of the planet doesn't have enough volume to support the "skin" anymore. NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft, which orbited the planet from 2011 to 2015, mapped these in incredible detail. The planet has likely shrunk by as much as 4.4 miles (7 kilometers) in radius since its crust first hardened billions of years ago.

Comparing Mercury to Other Worlds

To really understand where Mercury fits in the cosmic neighborhood, you have to look at its peers.

- Mercury vs. The Moon: Mercury is about 1.4 times larger than Earth’s Moon. They look like twins, but Mercury is much, much heavier because of that iron core.

- Mercury vs. Mars: Mars is nearly twice as large as Mercury. If Mercury is a tennis ball, Mars is a grapefruit.

- Mercury vs. Ganymede: This is the ego-bruiser. Ganymede, a moon of Jupiter, has a diameter of 3,273 miles. Mercury is only 3,032 miles. Mercury is literally the "runt" of the major spherical bodies in the inner solar system.

There is a certain irony in the fact that Mercury, named after the swift Roman messenger god, is so diminutive. It zips around the sun in just 88 days. Its small size and proximity to the Sun mean it has no moons of its own. It simply doesn't have the gravitational "reach" to capture a passing rock and keep it in orbit without the Sun snatching it away.

The Density Paradox

You’d expect a small planet to be light. But Mercury is the second densest planet in the solar system, right behind Earth. If you adjusted for "gravitational compression" (the way Earth's massive weight squeezes its own core), Mercury would actually be the densest planet of all.

This high density is a direct result of its Mercury size and composition. Because the core is so huge relative to the rest of the planet, it creates a magnetic field. It’s a weak one—only about 1% as strong as Earth’s—but the fact that it exists at all on such a small, slowly rotating world was a massive shock to scientists when the Mariner 10 mission first detected it in the 1970s.

Small planets aren't supposed to have active cores. They are supposed to cool down and "die" geologically very quickly. Yet, Mercury persists.

Living (or not) on a World This Small

If you were to stand on Mercury, the Sun would look three times larger than it does on Earth. The sky would be pitch black because there’s almost no atmosphere to scatter the light. Because the planet is so small, the horizon would feel closer.

The lack of size also means a lack of an atmosphere. Mercury has what is called an "exosphere." It’s a thin layer of atoms blasted off the surface by the solar wind and micrometeoroid impacts. Without a thick blanket of air to trap heat, the temperature swings are the most extreme in the solar system. You’d go from 800 degrees Fahrenheit (430 Celsius) during the day to -290 degrees Fahrenheit (-180 Celsius) at night.

Size affects everything. It affects how a planet holds heat, how it generates a magnetic field, and whether it can keep an atmosphere. Mercury is the perfect laboratory for seeing what happens when a planet is pushed to the absolute limit of "smallness."

The BepiColombo Factor

Right now, a joint mission between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) called BepiColombo is on its way to Mercury. It’s scheduled to enter orbit in late 2025 or early 2026. One of its primary goals is to figure out why Mercury’s core is so disproportionately large.

We are likely going to find out that the Mercury size we know is just the leftover "skeleton" of a much more impressive world that existed billions of years ago. By studying the magnetic field and the chemical composition of the surface, BepiColombo will tell us if Mercury was born this way or if a catastrophic collision redefined its destiny.

Summary of the "Small" Facts

If you're trying to wrap your head around the scale of the first planet from the Sun, remember these specific points. Mercury is just barely larger than our Moon. It is smaller than the largest moons in our solar system. It is shrinking as it cools, creating massive cliffs that scar its surface. Its gravity is weak enough that you could jump over a car, but its core is so dense that it behaves like a much larger celestial body.

Understanding Mercury isn't just about memorizing a diameter of 3,032 miles. It’s about realizing that in space, size isn't always tied to importance or complexity. Mercury is a dense, shrinking, metallic anomaly that defies our standard models of how planets should behave.

Actionable Insights for Amateur Astronomers and Space Fans

If you want to experience Mercury's size and presence for yourself, it's not as easy as looking at Mars or Jupiter.

💡 You might also like: Nuclear Reactor Safety: What Most People Get Wrong

- Find the "Elongation": Mercury is so close to the Sun that it’s usually lost in the glare. You can only see it during "greatest elongation"—the point where it appears furthest from the Sun in our sky. Check an astronomy app like SkySafari or Stellarium to find these dates.

- The Twilight Window: You generally only have a 30-to-60-minute window just after sunset or just before sunrise to spot it. It will look like a bright, yellowish-white star very low on the horizon.

- Binoculars Help: Because it’s so small and often obscured by atmospheric haze near the horizon, a decent pair of 10x50 binoculars will make it much easier to pop out from the twilight glow.

- Watch the Phase: If you have a telescope, you’ll notice that Mercury has phases just like the Moon. Because of its size and orbit, you’ll see it as a crescent or a "half-Mercury" depending on where it is relative to Earth.

Exploring Mercury reminds us that even the runts of the solar system have massive stories to tell. Its tiny stature belies a violent history and a surprisingly active present.

Next Steps:

- Check a 2026 celestial calendar for the next "Greatest Eastern Elongation" to see Mercury with your own eyes.

- Follow the BepiColombo mission updates as it prepares for its final orbit insertion to get the latest high-resolution data on the planet's shrinking crust.