You've probably been there. Staring at a whiteboard or a LeetCode screen, trying to remember if merge sort best case is somehow better than its average performance. It's a trick question. Most sorting algorithms—think Bubble Sort or Insertion Sort—have a "dream scenario." If you give Insertion Sort a list that is already perfectly sorted, it just breezes through in $O(n)$ time. It’s happy. It’s fast.

Merge sort isn't like that. It’s stubborn.

Whether you hand it a chaotic mess of random integers or a perfectly sequenced list of names, merge sort performs almost exactly the same amount of work. This consistency is its greatest strength, but for anyone looking for a "best case" shortcut, it’s a bit of a letdown. Understanding why this happens requires looking at how the "divide and conquer" philosophy actually plays out in memory.

The Mathematical Reality of Merge Sort Best Case

In computer science, we usually talk about Big O notation to describe the upper bound of an algorithm's growth. For merge sort, the time complexity is $O(n \log n)$. This applies to the worst case, the average case, and yes, the merge sort best case.

👉 See also: Apple University Village Seattle: Why It’s Actually Worth the Trip

Why? Because the algorithm is structurally rigid.

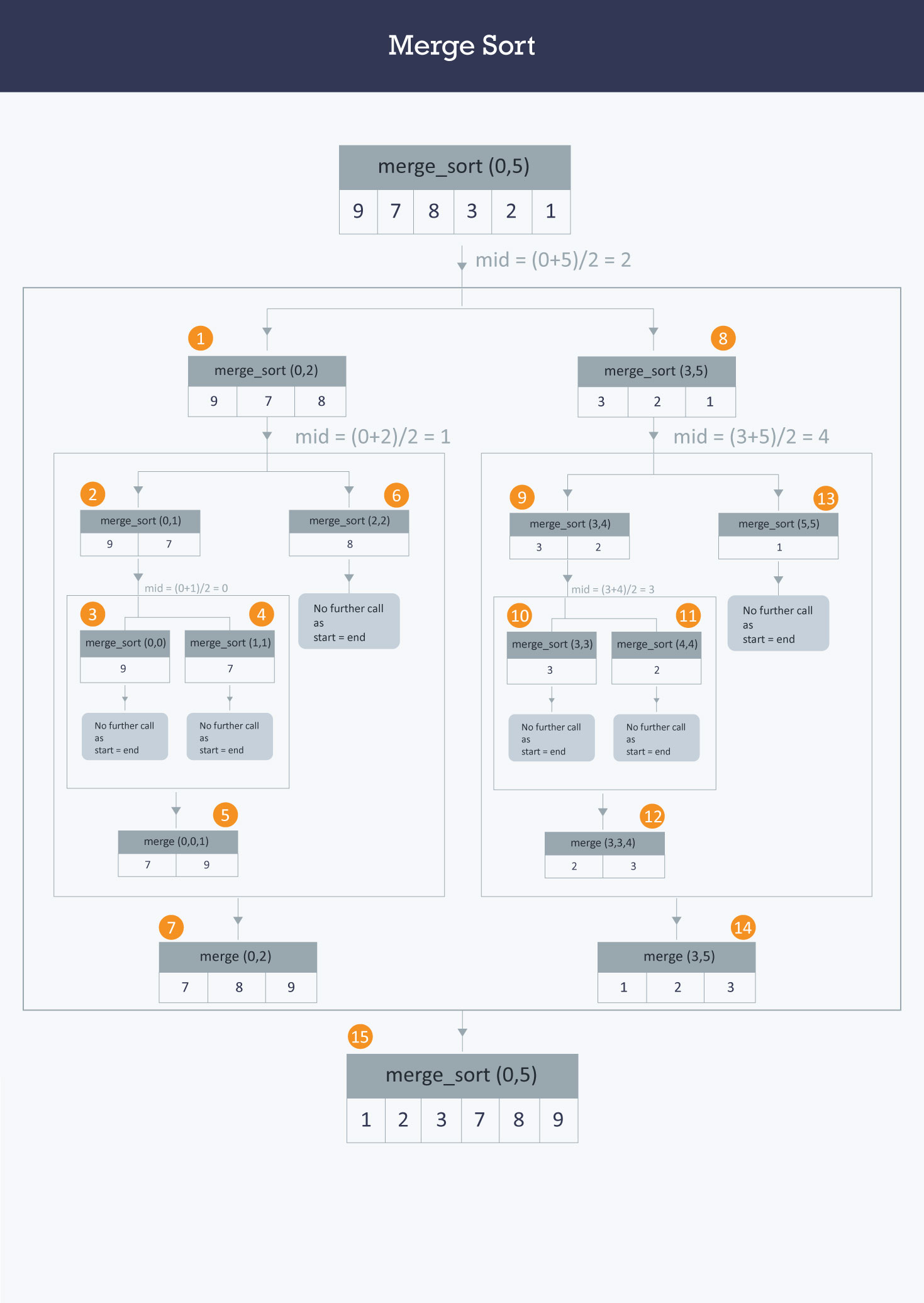

When you call a merge sort function, the first thing it does is split the array in half. It doesn’t check if the array is already sorted. It doesn't care. It recursively divides the data until it reaches base cases of single-element arrays. A single element is, by definition, sorted. Then comes the "merge" phase, where the real work happens.

Even if the two halves you are merging are already in the correct order, the algorithm still has to compare the elements to verify that fact. It has to move them from the original sub-arrays into a temporary workspace. John von Neumann, who is credited with the development of merge sort in 1945, designed it for efficiency on large datasets, specifically for the EDVAC computer. Back then, the goal was predictable performance on tape drives, not opportunistic shortcuts.

How the Comparison Count Shifts

While the Big O remains $O(n \log n)$, there is a tiny, almost imperceptible nuance in the number of comparisons. If you provide a perfectly sorted array, the merge function will always pick elements from the same "half" first. This can lead to slightly fewer comparisons than a worst-case scenario where elements are interleaved.

Specifically, in a best-case merge, you might perform roughly $n/2$ comparisons per level of the recursion tree, whereas the worst case pushes closer to $n-1$. But in the world of asymptotic analysis, these constants are dropped. The "log n" levels of division remain constant. You are still doing the work. You are still using the memory.

The Memory Trade-off Nobody Likes

One thing that makes people shy away from merge sort in certain environments is its space complexity. Unlike Quick Sort, which can often be done "in-place," merge sort usually requires $O(n)$ additional space. It needs a "scratchpad" to hold the elements while it’s comparing and reordering them.

Imagine you're organizing a deck of cards. An in-place sort would involve swapping cards within your hand. Merge sort is like taking the deck, splitting it into two piles on a table, and then requiring a second table of the same size to lay out the new, sorted sequence. It’s clean. It’s stable. But it’s greedy for space.

This doesn't change in the merge sort best case. Even if the cards are already sorted, you’re still moving them from Table A to Table B. This is why, in high-performance systems where memory is tight (like embedded sensors or old-school game dev), you might see developers reach for Timsort or Heap Sort instead.

Where Reality Hits the Code

Let's look at a practical example. Suppose you have a list of 1,024 items.

$1,024$ is $2^{10}$.

The algorithm will divide the list 10 times.

At each level, it processes all 1,024 items.

In a "worst-case" scenario—perhaps an array where elements are perfectly staggered like $[2, 4, 6, 8]$ and $[1, 3, 5, 7]$—the merge step has to do the maximum number of comparisons to figure out which number comes next.

👉 See also: Log and Exponential Rules: Why Most Students (and Engineers) Still Struggle

In the merge sort best case, where the array is already $[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]$, the algorithm still does the 10 levels of division. It still hits the merge step. It sees that $1 < 5$, $2 < 5$, $3 < 5$, and $4 < 5$. It finishes one side and then just copies the rest of the second side over. It's technically faster by a few CPU cycles because the "copying" logic might be more optimized than the "comparison" logic, but the fundamental workload hasn't moved the needle on the complexity graph.

The Stability Factor

Why do we bother with it if it doesn't have a fast best-case? Stability.

Merge sort is a "stable" sort. This means if you have two items with the same value—say, two different "John Smiths" in a database—merge sort guarantees they will stay in the same relative order they were in before the sort. For complex data objects, this is huge. Most "fast" versions of Quick Sort are not stable. If your data integrity relies on the original order of equal elements, you pay the $O(n \log n)$ price of merge sort willingly.

Natural Variations: Timsort and Modern Fixes

Because the lack of a "fast" merge sort best case is a known limitation, modern languages don't usually use a "pure" merge sort. Python, Java, and Rust often use Timsort.

Timsort is a hybrid. It looks for "runs"—sequences of data that are already sorted. If it finds a sorted run, it leaves it alone and moves on to the next one, eventually merging these runs together.

- It identifies a "natural run" (already sorted).

- It uses Insertion Sort for small chunks (which is very fast for small, nearly sorted data).

- It uses the merging logic for the big-picture organization.

In Timsort, the best case actually is $O(n)$. It bridges the gap between the predictability of merge sort and the opportunism of insertion sort. But if you are in a technical interview or a CS101 exam, you need to stick to the classic answer: Merge sort is always $O(n \log n)$.

Common Misconceptions

People often confuse "Best Case" with "Average Case."

In many algorithms, the average case is much closer to the worst case. With merge sort, they are essentially identical. There’s a common myth that you can "optimize" merge sort by adding a check: if (array[mid] <= array[mid+1]) return;.

While this sounds clever, it often slows down the algorithm on average. You're adding a comparison to every single recursive step. Unless your data is almost always sorted, that extra "check" becomes overhead that eats away at your performance. Honestly, it's usually not worth it.

Applying This Knowledge

If you’re deciding whether to use merge sort in a real-world project, don't look for a "best case" performance boost. Use it if:

- Predictability is key: You need to know exactly how long the sort will take, regardless of the input.

- Stability is required: You’re sorting objects and need to maintain original order for tied values.

- Data is massive: Merge sort is excellent for external sorting (sorting data that doesn't fit in RAM) because it processes data sequentially.

- Linked Lists: Merge sort is actually the preferred way to sort linked lists because it doesn't require random access to elements, unlike Quick Sort.

If you are dealing with small arrays that are likely already sorted, and you have the flexibility, something like Insertion Sort or a hybrid approach will serve you better. But for the pure, academic version of merge sort, the "best case" is simply a steady, reliable climb up the logarithmic curve.

💡 You might also like: Buying Unlocked GSM Cell Phones Walmart: What Most People Get Wrong

To truly master this, try implementing a version of merge sort that tracks the number of comparisons made. Run it once with a random array and once with a sorted array of the same size. You'll see the numbers are remarkably close. That's the hallmark of a consistent algorithm. It doesn't gamble on your data being "easy." It just gets the job done.

Next Steps for Implementation

If you want to optimize your sorting logic beyond the standard implementation, start by benchmarking your specific data types. For most developers, the built-in sort functions in languages like Python or JavaScript are already using highly optimized hybrids like Timsort that handle the "best case" scenarios automatically. If you are writing your own for a low-level systems project, consider implementing "Natural Merge Sort," which actively looks for pre-sorted sequences to reduce the total number of merge passes required. This effectively gives you an $O(n)$ best case without losing the $O(n \log n)$ guarantee for chaotic data.