You’re standing in your backyard on a Tuesday night. It’s cold. You look up, and for a split second, a needle of light stabs through the dark. "Look, a falling star!" someone yells. But stars don't fall. If a star actually fell toward Earth, we’d be vaporized before we could even point a finger. What you actually saw was a meteor.

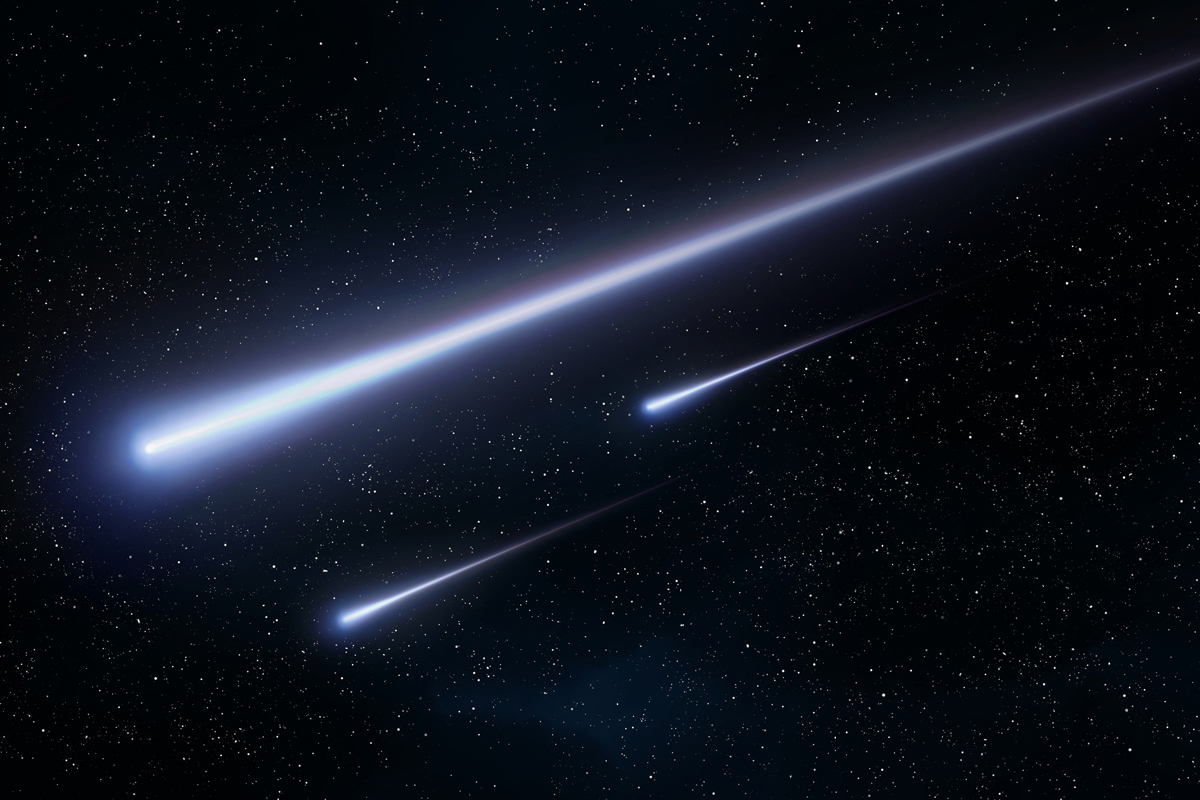

Basically, a meteor is just a streak of light. That's it. It’s not the rock itself, and it’s definitely not a star. It’s the visual evidence of a high-speed collision between a space pebble and our atmosphere. Space is incredibly messy. It’s filled with "leftovers" from the birth of our solar system about 4.6 billion years ago. When one of those leftovers—usually a bit of dust or rock—decides to kamikaze into Earth’s gas envelope, we get a show.

Most of these things are tiny. Imagine a grain of sand. Now imagine that sand traveling at 45 miles per second. At those speeds, the air doesn't just get out of the way; it compresses violently, heats up to thousands of degrees, and creates a glowing trail of ionized gas. That glow is the meteor.

✨ Don't miss: Where to Find Reading List on iPhone: Why Most People Keep Missing It

The Name Game: Meteoroid, Meteor, and Meteorite

Scientists are pretty picky about names. It’s kinda like the difference between a caterpillar, a cocoon, and a butterfly, except with more fire and kinetic energy.

- Meteoroid: This is the object while it’s still in space. It's just a rock minding its own business. They range in size from a speck of dust to a massive boulder.

- Meteor: This is the light show. The moment the rock hits the atmosphere and starts glowing, it becomes a meteor.

- Meteorite: If the rock is big enough or tough enough to survive the fiery descent and actually hit the ground, we call the leftover chunk a meteorite.

Most people use these interchangeably. Honestly, it doesn't matter much in casual conversation, but if you’re talking to an astronomer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, you’ll want to get it right.

Why Do They Glow Anyway?

It’s easy to assume the glow comes from friction. You rub your hands together and they get warm, right? But with a meteor, it’s mostly about adiabatic compression. The air in front of the falling rock is being smashed together so fast that the temperature skyrockets. It happens in an instant.

This intense heat creates a plasma trail. The atoms in the air and the vaporized material from the rock lose electrons. When those electrons find their way back home, they release energy as light. Depending on what the rock is made of, you might see different colors. Sodium creates an orange-yellow glow. Nickel looks green. If you see a vivid purple or blue streak, you’re likely looking at magnesium or calcium being shredded by the atmosphere.

Fireballs and Bolides

Sometimes, the light is so bright it casts shadows. These are "fireballs." NASA defines a fireball as a meteor that is brighter than Venus in the night sky.

💡 You might also like: Why the HP Sprocket Mini Printer is Still the Only Gadget Worth Carrying to a Party

Then there are bolides. A bolide is a fireball that explodes. Imagine a rock the size of a grapefruit hitting the air at Mach 50. The structural stress becomes too much, and the rock literally detonates in mid-air. The Chelyabinsk event in Russia back in 2013 was a massive bolide. It was brighter than the sun for a moment and the shockwave blew out windows across an entire city. People were injured not by the rock itself, but by the glass shards flying into their living rooms.

The Mystery of Meteor Showers

You’ve probably heard of the Perseids or the Geminids. These aren't just random occurrences. They’re predictable.

Earth orbits the sun in a very specific path. Comets do the same, but they’re messy. As a comet gets close to the sun, it sheds ice and dust, leaving a trail of debris behind it like a cosmic breadcrumb trail. Every year, at the same time, Earth’s orbit intersects with these debris trails.

Think of it like driving a car through a swarm of bugs. You’re going to hit a lot of them all at once. During the Perseids, which happen every August, we’re actually driving through the tail of Comet Swift-Tuttle.

Where Do These Rocks Come From?

Most meteors originate from the Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter. Collisions happen there all the time. A nudge here, a bump there, and suddenly a rock is sent on a collision course with Earth.

Others are bits of comets. Comets are "dirty snowballs"—mixtures of frozen gases and rock. When they get near the sun, they start to evaporate, releasing the grit trapped inside.

A tiny percentage actually comes from the Moon or Mars. When a giant asteroid slams into Mars, it can kick up rocks with enough force to escape Martian gravity. Those rocks drift through space for millions of years until they happen to cross paths with us. We know this because we’ve found meteorites on Earth that have the exact chemical signature of the Martian atmosphere. It's wild to think you could be holding a piece of another planet in your hand.

Why We Should Care

Studying a meteor isn't just for hobbyists with telescopes. It’s about planetary defense. While most of what hits us is harmless dust, bigger objects are out there.

Organizations like the B612 Foundation and NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office spend their time tracking Near-Earth Objects (NEOs). We want to know if something big is coming long before it enters the "meteor" phase.

But there’s also the science of our origins. Because these rocks have been floating in the vacuum of space for billions of years, they are like time capsules. They contain the pristine chemistry of the early solar system. Some meteorites even contain amino acids—the building blocks of life. There’s a theory called panspermia which suggests that the ingredients for life on Earth were actually delivered by meteors and comets billions of years ago. We might literally be made of space dust.

How to Actually See One

You don’t need a telescope. In fact, telescopes are terrible for seeing meteors because they have a narrow field of view. You want your eyes.

- Get away from city lights. Light pollution is the enemy. Find a dark park or a rural road.

- Let your eyes adjust. It takes about 20 to 30 minutes for your "night vision" to fully kick in. Put your phone away. The blue light from the screen will ruin your progress.

- Check the calendar. While "sporadic" meteors happen every night, your best bet is during a major shower.

- Look up, but don't stare at one spot. Let your peripheral vision do the work. It’s better at detecting motion and faint light.

What to Do if You Find a Potential Meteorite

If you’re out hiking and you see a rock that looks out of place, it might be a meteorite. But be warned: most "meteorites" are actually "meteor-wrongs." Slag from old factories or iron-rich terrestrial rocks often fool people.

💡 You might also like: How to Measure on Google Earth Without Getting Lost in the Menu

Real meteorites are usually heavy for their size because they contain a lot of iron and nickel. They often have a "fusion crust"—a thin, dark, glassy coating caused by the heat of entry. They are also usually magnetic. If a magnet doesn't stick to it, it’s probably just a regular Earth rock. If you think you’ve found the real deal, don't clean it with water. You’ll ruin the scientific value. Put it in a clean bag and contact a local university geology department.

Actionable Steps for Stargazers

- Download a Dark Sky App: Use apps like Clear Outside or Dark Site Finder to locate areas near you with minimal light pollution.

- Track Meteor Showers: Use a site like TimeandDate or the IMO (International Meteor Organization) to find the "peak" nights for upcoming showers. The peak is when the Earth is in the densest part of the debris trail.

- Contribute to Science: If you see a particularly bright fireball, you can report it to the American Meteor Society. They use crowd-sourced data to track the trajectory of fireballs and locate potential fall zones for meteorites.

- Equipment Check: If you're serious, buy a comfortable reclining lawn chair. Staring straight up for two hours will wreck your neck. A warm blanket and a thermos of coffee are mandatory, even in summer.

Meteors are a constant reminder that we live in a shooting gallery. Every flash in the sky is a tiny piece of history ending its multi-billion-year journey by slamming into our home. It's a beautiful, violent, and utterly normal part of living on a planet. Next time you see that "falling star," remember you're watching a cosmic collision in real-time.