Michael Palin almost didn't get to play Pontius Pilate. Imagine that. The most iconic, lisping, "Biggus Dickus" obsessed Roman governor in cinema history might have been someone else. But in the sweltering heat of Tunisia in 1978, Palin didn't just play the role; he basically weaponized it.

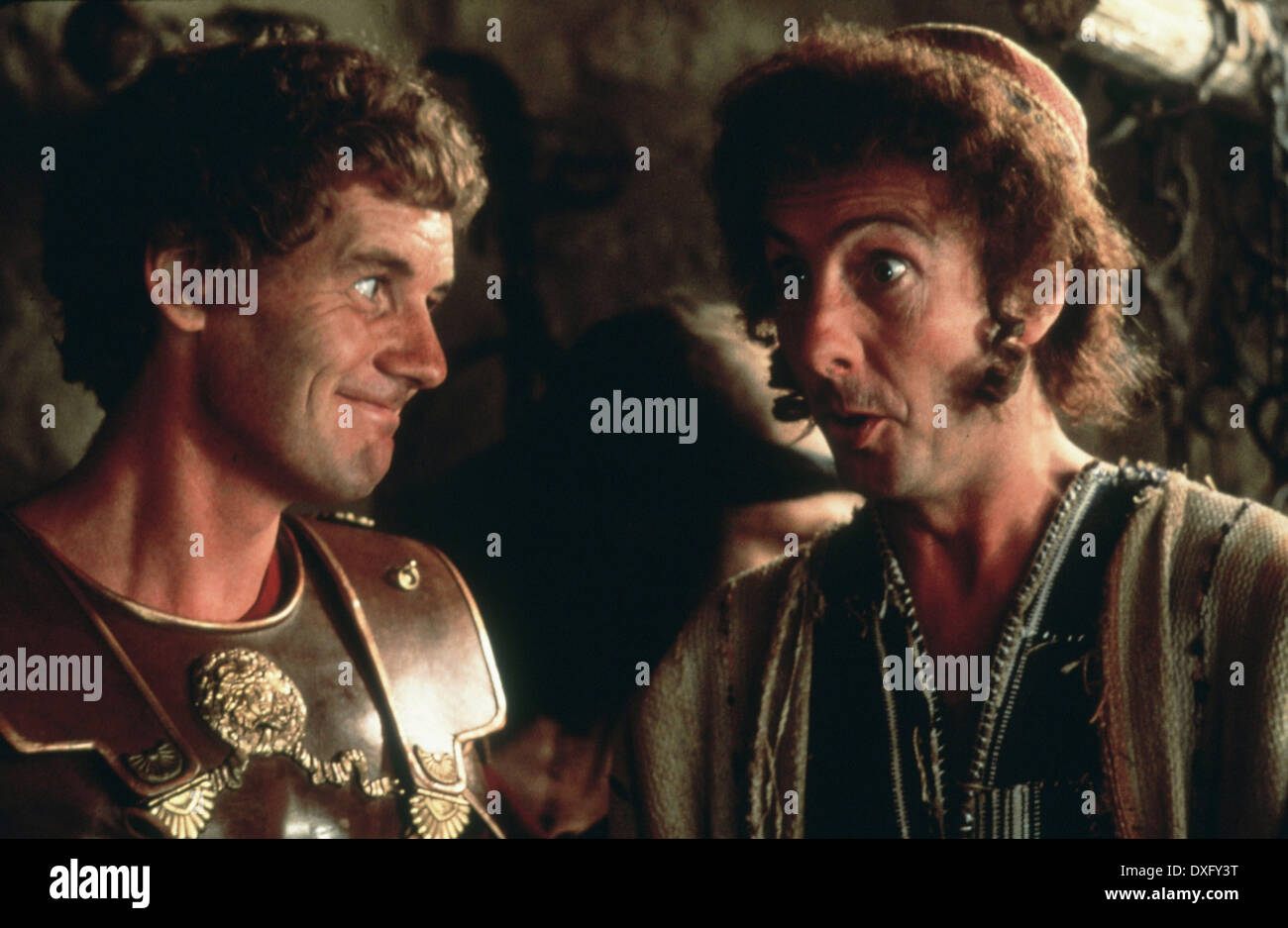

Honestly, if you watch the movie now, you've probably noticed those Roman soldiers in the background. They aren't just acting. They are genuinely, painfully trying not to explode into laughter. Palin was deliberately pushing them. He’d get right in their faces, inches away, and deliver those ridiculous lines about his "fwiend in Wome" with absolute, deadpan sincerity. It was psychological warfare with a comedic twist.

Why Michael Palin Life of Brian Remains a Comedy Masterclass

When people talk about Michael Palin Life of Brian performances, they usually jump straight to Pilate. It makes sense. It’s the flashy role. But Palin actually played about a dozen characters in the film. He was Francis, the fiery (and slightly pedantic) member of the People's Front of Judea. He was the "Boring Prophet" who just wouldn't stop rambling. He was even one of the Wise Men in the opening scene.

The range is actually kind of exhausting to think about.

One minute he’s a stuttering ex-leper complaining about his loss of livelihood—because Jesus went and cured him—and the next he’s a high-ranking Roman official. This versatility is what made the Python troupe work, but Palin had this specific brand of "nice guy" energy that made his more aggressive or absurd characters feel even weirder.

The Biggus Dickus Secret

There’s a common legend that the extras in the Pilate scene didn't know what Palin was going to say. That’s not entirely true. They had a script. However, the way Palin played it changed with every take. He’d hold the pauses longer. He’d spray a little more saliva. He was daring them to break.

The centurion standing next to him, played by John Cleese, had to maintain a mask of stone. But the younger extras? They were visibly shaking. Some of those reactions that made the final cut are 100% real moments of people losing their minds because Michael Palin was being relentlessly, aggressively funny.

Filming in the Tunisian Heat

Tunisia wasn't exactly a vacation. The Pythons were using sets left over from Franco Zeffirelli's Jesus of Nazareth. Talk about recycling. Palin’s own diaries from the time—which are a goldmine for anyone obsessed with this era—reveal a lot of the grind. They were staying in Monastir and Sousse, dealing with 100-degree weather while wearing heavy wool togas and Roman armor.

🔗 Read more: Snoop Dogg Snoop Lion: Why the Most Confusing Era in Rap History Actually Made Sense

Palin noted that some of the Tunisian extras, who had worked on the more serious Zeffirelli production, were a bit confused. They’d tell the Pythons, "Mr. Zeffirelli wouldn't have done it like that."

No kidding.

The Blasphemy War and George Harrison

It’s easy to forget that this movie was nearly killed before it started. EMI Films pulled the plug at the last second because the head of the company, Lord Bernie Delfont, actually read the script and got cold feet. He thought it was blasphemous.

This is where the story gets legendary. Eric Idle called up his friend George Harrison. George, being a massive Python fan and having way too much money, basically funded the entire movie because he "wanted to see it." He mortgaged his house and his office. It was, as Idle later called it, "the most expensive cinema ticket in history."

Palin was always the one who defended the film's "message" the most reasonably. He famously went on the chat show Friday Night, Saturday Morning with John Cleese to debate the Bishop of Peterborough and Malcolm Muggeridge. While the critics were calling the film "squalid" and "shameful," Palin sat there with his trademark calmness. He pointed out the obvious: the film wasn't mocking Jesus. It was mocking the people who followed him blindly without thinking for themselves.

The "I'm Not" Moment

There’s a tiny moment in the film that perfectly encapsulates the Michael Palin Life of Brian era. It’s the scene where Brian (Graham Chapman) tells the crowd, "You are all individuals!" and they shout back in unison, "Yes! We are all individuals!"

💡 You might also like: Why The Daily Show Season 30 Episode 104 Is Making Everyone Talk About Late Night Again

Then, one lone voice—played by Terence Bayler, though Palin often recounted the story with glee—pipes up: "I'm not."

That one line was an improvisation. It wasn't in the original plan. But it stayed because it hit the core of what the Pythons were trying to say. Palin loved those small, human glitches in the system.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Creatives

If you’re looking to dive deeper into the Michael Palin Life of Brian history or apply his approach to your own work, here’s what you should actually do:

- Read "The Python Years" Diaries: If you want the real, unvarnished truth about the production, Michael Palin’s published diaries are better than any documentary. He wrote them at the time, so it’s not just hazy nostalgia.

- Watch the "Friday Night, Saturday Morning" Debate: It’s available on YouTube. Watch it not just for the comedy, but to see how Palin handles high-pressure, bad-faith arguments with grace and intellect.

- Observe the Background Extras: Next time you watch the Pilate scenes, stop looking at Palin. Look at the soldiers. You’ll see the exact moment their professional resolve crumbles. It’s a lesson in "playing the reality" of a scene to make the comedy hit harder.

- Visit the Ribat of Monastir: If you ever find yourself in Tunisia, the Ribat is where most of the Jerusalem scenes were filmed. It’s still there, and you can walk the same ramparts where the People's Front of Judea argued about "what the Romans have ever done for us."

Palin’s legacy in Life of Brian isn't just about the funny voices. It's about the fact that he treated the absurdity with total commitment. Whether he was a Roman governor or a man following a "holy" shoe, he never winked at the camera. He lived in that world. And that’s why, even decades later, we’re still talking about it.