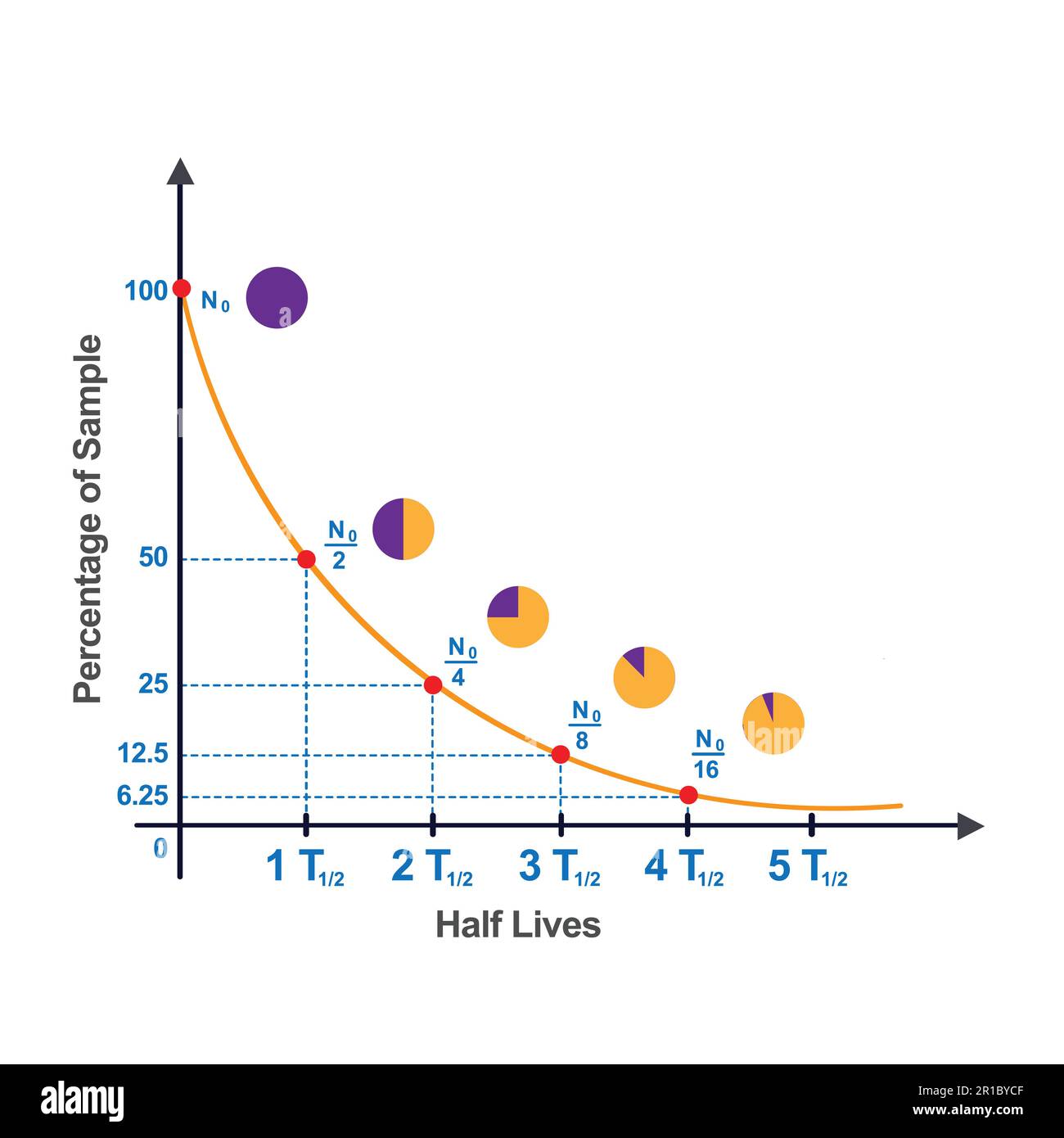

You’ve probably seen the classic "half-life" graph in a dusty textbook. It’s that perfect, smooth curve that looks like a playground slide, showing how a radioactive substance slowly disappears over time. It looks predictable. Orderly. Safe.

But honestly? That graph is a bit of a lie.

Nature doesn't care about our need for order. Nuclear decay half life is one of the weirdest, most counterintuitive things in physics because it combines total randomness with absolute mathematical certainty. You can’t predict when a single atom will "pop" and turn into something else. You just can’t. It’s like popcorn in a microwave; you know the bag will be full eventually, but you have no clue which kernel is going first.

Yet, when you have a billion atoms, that randomness turns into a clock so precise we use it to date the bones of pharaohs and power deep-space probes. It’s a weird paradox. If you’re trying to understand why some nuclear waste stays "hot" for ten thousand years while others are safe in a week, you have to get comfortable with the chaos.

The "Flipping Coin" Reality of Nuclear Decay Half Life

Most people think of decay as a slow rot. Like an apple turning brown. But that’s not it at all.

Think of it this way. Every radioactive atom is holding a coin. Every second, it flips that coin. If it lands on heads, the atom stays as it is. If it’s tails, the atom "decays"—it spits out a particle, releases a burst of energy, and transforms into a completely different element.

This is the core of nuclear decay half life. The "half-life" is simply the amount of time it takes for 50% of those atoms to flip "tails."

Here is where it gets trippy. If you have 1,000 atoms of Iodine-131 (which has a half-life of about 8 days), after 8 days, you’ll have 500 left. After another 8 days, you don’t have zero. You have 250. You’re always cutting the remaining pile in half.

The math follows a specific decay law:

$$N(t) = N_0 \left( \frac{1}{2} \right)^{\frac{t}{T_{1/2}}}$$

In this formula, $N(t)$ is the quantity remaining, $N_0$ is the initial amount, $t$ is the elapsed time, and $T_{1/2}$ is that specific half-life duration. It’s an exponential decline. It never truly hits zero—at least not for a very, very long time.

Why does the time vary so much?

It’s honestly staggering. Polonium-214 has a half-life of about 164 microseconds. Blink, and it’s gone. Meanwhile, Tellurium-128 has a half-life of $2.2 \times 10^{24}$ years. To put that in perspective, that is over 160 trillion times longer than the age of the universe.

Why the difference? It comes down to the "Strong Force" inside the nucleus. If the nucleus is packed in a way that’s slightly unstable, it’s like a Jenga tower leaning at a 45-degree angle. It wants to fall. If it's mostly stable, it's like a Jenga tower with one slightly loose block. It might take a billion years for a vibration to finally knock it over.

The Carbon-14 Misconception

When we talk about dating fossils, Carbon-14 is the celebrity. But most people get the "how" wrong. They think the bone is radioactive.

While you’re alive, you’re eating plants (or eating animals that ate plants). Those plants took in Carbon-14 from the atmosphere, which is constantly being replenished by cosmic rays hitting nitrogen. So, your body has a steady ratio of "normal" Carbon-12 and "radioactive" Carbon-14.

The moment you die? You stop eating.

The clock starts. The Carbon-14 in your bones starts its nuclear decay half life journey (about 5,730 years). By measuring how much Carbon-14 is left compared to the Carbon-12, scientists like those at the University of Oxford’s Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit can pinpoint when that heart stopped beating.

🔗 Read more: How Far Are We From the Moon? The Truth About That 238,855-Mile Gap

- Caveat: It’s not perfect. If a bone is older than 50,000 years, there’s so little Carbon-14 left that it’s basically impossible to measure accurately.

- The "Bomb Effect": Nuclear weapons testing in the 1950s and 60s actually doubled the amount of Carbon-14 in the atmosphere. This messed up the "natural" baseline, but it also gave scientists a "pulse" they can use to identify modern remains or even detect fake vintage wines.

The Health Reality: Short vs. Long Half-Lives

Which is more dangerous: a substance with a half-life of 2 minutes or 2,000 years?

Most folks would say 2,000 years. They’re usually wrong.

Basically, radioactivity is about "events per second." If a substance has a very short nuclear decay half life, it means it’s screaming through its energy. It’s throwing off massive amounts of radiation in a very short window. It’s a grenade.

A substance with a 2,000-year half-life is more like a slow-burning candle. It’s releasing energy slowly. You wouldn’t want to swallow it, but standing near it for a minute probably won't do much.

This is why medical isotopes used in PET scans, like Fluorine-18, have half-lives of only about 110 minutes. Doctors want the "glow" to see what's happening in your brain or heart, but they want that material gone from your system by the time you're heading home for dinner.

Potassium-40: You are radioactive

You should probably know that you’re slightly radioactive right now. Bananas are famous for this because they’re rich in potassium, and a tiny fraction of all potassium is the isotope K-40. It has a nuclear decay half life of 1.25 billion years.

Does this matter? Not really. Your body regulates potassium levels so strictly that eating ten bananas won't actually increase your radiation dose. But it's a great example of how "radioactive" doesn't always mean "glowing green monster."

How We Actually Use This Stuff in Tech

We don't just use this to look at old rocks. It powers things that can't be plugged in.

Take the Voyager spacecraft. It’s been flying for over 45 years. You can’t use solar panels out past Neptune; the sun is just a bright star at that point. Instead, it uses Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs). Essentially, it's a chunk of Plutonium-238.

As the Plutonium undergoes its nuclear decay half life (87.7 years), it gets physically hot. It glows red-hot just from its own decay. Engineers use thermocouples to turn that heat directly into electricity. It’s a "nuclear battery" that lasts for generations.

But there's a downside. As the material decays, the "battery" loses power. Voyager has to keep turning off its instruments one by one as the "heat" dies down. It's a slow, predictable fade into the dark.

The Nuclear Waste Problem

This is the part everyone argues about. When we talk about spent nuclear fuel, we’re dealing with a cocktail of different isotopes.

- The Sprinters: Isotopes like Iodine-131. They’re terrifyingly radioactive but gone in weeks.

- The Middle-Distance Runners: Cesium-137 and Strontium-90. Half-lives of around 30 years. These are the real problem for human health because they stay around for centuries and the body can mistake them for calcium or potassium.

- The Marathoners: Plutonium-239. Half-life of 24,000 years.

Because of the way nuclear decay half life works, we have to design storage facilities that can last longer than human civilization has existed. The Onkalo spent nuclear fuel repository in Finland is the first of its kind, bored deep into 2-billion-year-old bedrock. They have to assume that in 10,000 years, nobody will speak Finnish or English, so they have to figure out how to say "Don't dig here" using only architecture and universal symbols.

Actionable Insights: What You Should Actually Do

Understanding half-life isn't just for physicists. It’s for making sense of the world.

- Check your home for Radon: Radon-222 is a gas that comes from the natural decay of uranium in the soil. It has a half-life of 3.8 days. It’s the second leading cause of lung cancer. Since it decays quickly, it builds up "progeny" (other radioactive elements) in your lungs. If you live in a basement or a rocky area, get a $20 test kit. It’s the one time nuclear decay half life actually affects your daily safety.

- Don't freak out about "Medical Radiation": If you get a scan with a tracer, remember the "half" part. By the time you wake up the next morning, most of that stuff has already flipped its "tails" and turned into something stable.

- Look at the math, not the fear: When you hear about a "spill," ask what the isotope is. If it’s something with a half-life of hours, the problem is self-correcting. If it’s years, that’s when you worry about the soil.

The universe is fundamentally unstable. Everything is eventually turning into something else. We’re just lucky enough to live in a window where the half-lives of the stuff we’re made of—Carbon, Oxygen, Nitrogen—are so long they’re effectively infinite.

To dig deeper into the specific decay chains of various elements, you can check the IAEA’s Live Chart of Nuclides. It’s an interactive map of every isotope known to man. It's a bit overwhelming at first, but it shows you exactly how every atom eventually finds its way to stability.

Next time you see that smooth curve in a textbook, just remember the coin flips. Millions and billions of tiny, random coin flips, all happening at once, dictating the age of the earth and the future of our energy.