You’ve probably seen the simulators. You type in your city, pick a payload—maybe a "Fat Man" or a modern Tsar Bomba—and click a button to watch the concentric circles of doom swallow your neighborhood. It's morbidly addictive. But here’s the thing: most people using a nuke bomb radius map are looking at the wrong numbers. They focus on the fireball. Sure, the fireball is terrifying, but it’s actually the smallest part of the problem for the vast majority of people.

Modern nuclear strategy isn't just about the "boom." It’s about thermal radiation, overpressure, and the weird, unpredictable way geography messes with physics. If you're sitting in a valley, the blast wave might bounce off a ridge and hit you twice. If you're behind a skyscraper, the building might shield you from the initial flash but then collapse on your head thirty seconds later.

Real experts, like Alex Wellerstein, the creator of NUKEMAP, often point out that these tools are educational, not 100% predictive. Why? Because the atmosphere isn't a vacuum. Humidity, air pressure, and even the time of year change how far a blast travels.

How a Nuke Bomb Radius Map Actually Works (And Where It Fails)

When you look at a nuke bomb radius map, you're seeing "idealized" circles. The math is usually based on the "Effects of Nuclear Weapons" by Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan. This is the gold standard, the "bible" of blast physics.

🔗 Read more: Inside Marine One Helicopter: What Most People Get Wrong About the President's Flying Office

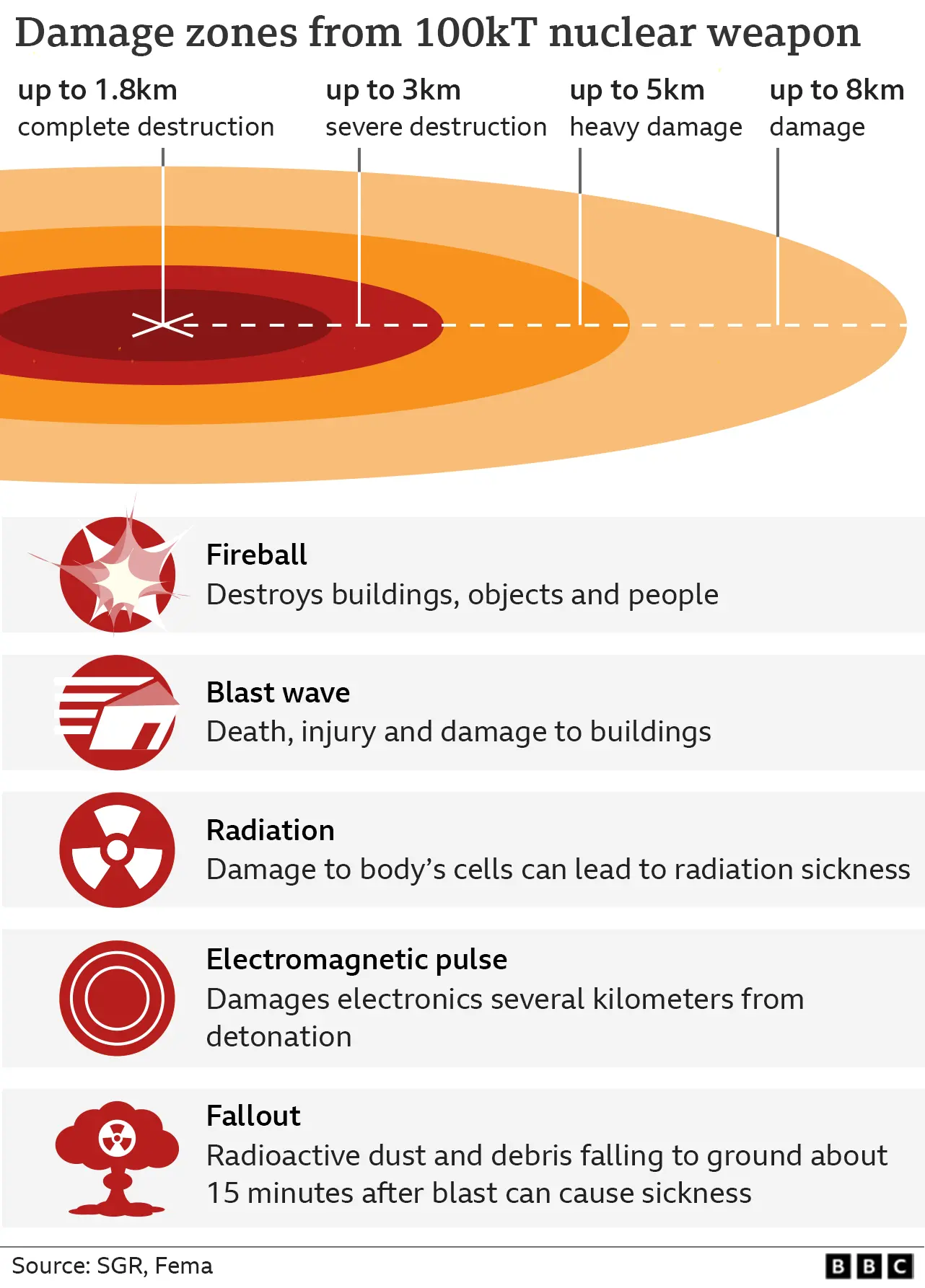

The first circle is the radiation fireball. This is the point where the bomb's internals are literally hotter than the center of the sun. Everything is plasma. But move out just a few miles, and the danger changes. You hit the "5 psi" overpressure zone. In this area, most residential buildings just... stop existing. They crumble. This isn't a movie where things catch fire and then blow up. The air itself becomes a solid wall of force that moves at supersonic speeds.

Most people don't realize that the "thermal radiation" ring is almost always the largest. On a clear day, a 1-megaton blast can cause third-degree burns up to 11 miles away. If it’s a foggy day? That radius shrinks significantly because the water droplets in the air scatter the light. A nuke bomb radius map usually assumes a clear day. If it’s raining when the bomb goes off, you might survive in a spot where you’d otherwise be toast.

The Height of Burst Problem

Are we talking about a ground burst or an air burst? This is the most critical variable. If a weapon hits the ground, it kicks up thousands of tons of dirt. That dirt becomes radioactive and falls back down as "fallout." This is the stuff that kills people hundreds of miles away, days later.

If it’s an air burst—detonated a few thousand feet up—the blast wave is maximized. The wave hits the ground and "reflects" back up, combining with the original wave to create a "Mach stem." It's basically a super-wave. Air bursts are "cleaner" in terms of immediate fallout, but they level much larger areas. Most maps let you toggle this. If you don't toggle it, you aren't getting the full picture.

Misconceptions About the "Instant Death" Zone

We have this idea that if you’re on the map, you’re dead. That’s not true. Humans are surprisingly resilient to pressure, but incredibly fragile when it comes to flying glass. In the 190-250 range of the "light damage" zone, the pressure won't kill you. The 10,000 shards of window glass flying at 100 mph will.

- The Fireball: You're vapor. No debate there.

- The Heavy Blast Zone: Concrete buildings might stand, but the interiors are gutted.

- The Moderate Blast Zone: This is where the real casualties happen. Most people are injured by collapsing roofs and fire.

- The Thermal Zone: If you are outside, you get burned. If you are behind a wall, you might be okay—for the first ten seconds.

Then comes the firestorm. In Hiroshima, the "U-shaped" damage pattern wasn't just from the blast. It was a mass fire that sucked oxygen out of the air for blocks. A nuke bomb radius map has a hard time calculating firestorms because they depend on how much "fuel" (trash, wooden houses, gas lines) is in your city.

The Fallout Tail: The Part Maps Get Wrong

If you look at a tool like NUKEMAP or the MISSILEMAP, you’ll see a long, thin oval stretching away from the blast site. That’s the fallout plume. But look at a real weather map. Winds don't blow in straight lines. They shear. The wind at ground level might be blowing North, while the wind at 30,000 feet—where the mushroom cloud lives—is screaming East.

Real-world fallout looks more like a jagged inkblot than a smooth oval. In the 1954 "Castle Bravo" test, the fallout went in a completely unexpected direction because of wind shear, irradiating the crew of a Japanese fishing boat, the Lucky Dragon No. 5, and the residents of Rongelap Atoll. This is the danger of relying too much on a static nuke bomb radius map. It gives a false sense of "safe zones."

Why Yield Matters Less Than You Think

A 100-kiloton bomb and a 1-megaton bomb (which is 1,000 kilotons) don't have a 10x difference in destruction radius. It’s more like a 2x or 3x difference. This is due to the "cube-root law" of blast scaling. To double the distance of a certain pressure level, you need to octuple (8x) the yield.

Basically, big bombs are "wasteful" in military terms. This is why modern nuclear powers like the US and Russia moved away from giant 50-megaton monsters and toward MIRVs (Multiple Independently Targetable Reentry Vehicles). They’d rather hit a city with five 100-kiloton warheads in a pattern than one giant 5-megaton bomb in the center. The "pattern" covers much more area on a nuke bomb radius map than a single big circle.

Practical Survival Nuance

If you are ever in a situation where you see the flash—and you aren't instantly vaporized—you have a few seconds. The light travels at the speed of light. The blast wave travels roughly at the speed of sound (a bit faster near the center).

- Don't look at the flash. It will blind you instantly, permanently.

- Drop to the ground. If you are under a sturdy table, get there.

- Open your mouth slightly. This helps equalize pressure in your eardrums so they don't burst.

- Stay down. There are often two blast waves—the initial one and a "suction" wave that pulls air back toward the center.

Most people who survive the initial minute will be facing "The Great Choice": Stay or Go? If you are in the fallout path, you have to decide if your building provides enough "protection factor." A basement with thick concrete overhead is usually better than trying to drive through a panicked, clogged highway while radioactive dust falls on your car.

Actionable Steps for Reality-Based Planning

Stop just clicking "Detroit" or "London" on a map and feeling scared. If you actually want to understand your risk, you need to look at layers.

👉 See also: Why No Number Caller ID Calls Keep Happening and How to Stop Them

- Check the prevailing winds: Use a site like Windy.com to see where the air at 10km altitude usually goes in your area. That is your "Red Zone."

- Identify "Shadow Zones": Look for hills or large geographic features between you and likely targets (military bases, major ports, city centers). These can deflect the "overpressure" wave.

- Assess your structure: A wood-frame house is basically a pile of toothpicks in the 5 psi zone. A reinforced concrete basement is a different story.

- Understand the "EMP" Myth: A single high-altitude burst will fry electronics, but if you are close enough for the nuke bomb radius map to matter, the EMP is the least of your worries. Your phone won't work anyway because the towers will be gone.

The most important thing to remember is that these maps are models. They are math equations visualized. They don't account for a broken water main flooding your shelter or the fact that a specific skyscraper might act as a "wind tunnel" for the blast. Use them as a starting point for education, but don't treat those circles as gospel. Geography always wins.