Ever sat through a production of Oliver! and wondered why Fagin seems more like a kooky uncle than a child-trafficking nightmare? You’re not alone. Honestly, if you only know Charles Dickens through the lens of a local theater or the West End, you've only met half the family. The oliver twist play characters we see today are often softer, louder, and way more musical than the grime-covered wretches Dickens first scratched onto paper in 1837.

Translating a massive Victorian novel into a two-hour stage show is basically surgery. You have to cut limbs to save the body. This means some of the most fascinating (and terrifying) characters from the book never even make it to the stage lights.

The Transformation of Fagin: Villain or Victim?

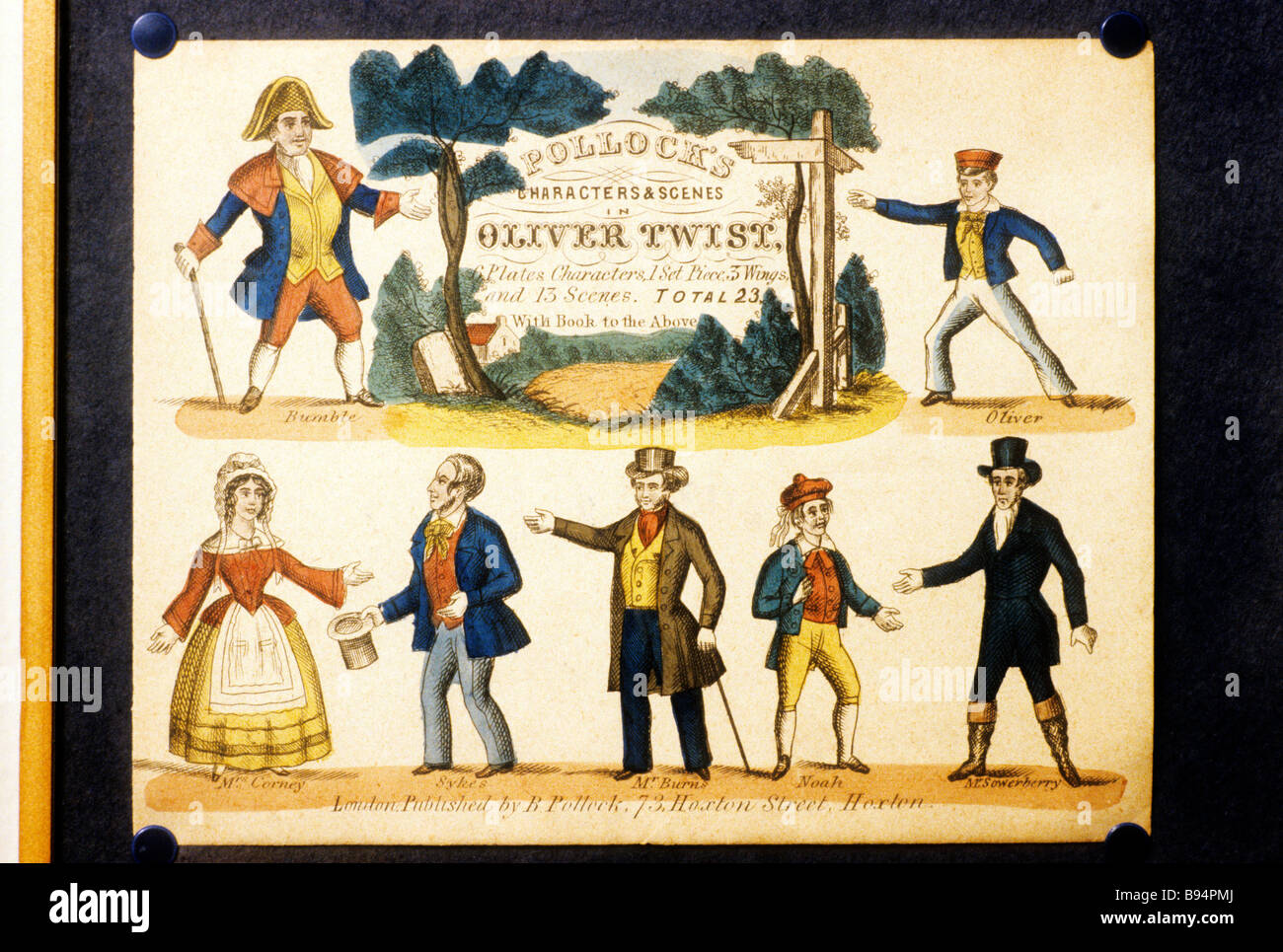

In the original book, Fagin is described as a "shrivelled old Jew" with matted red hair. He’s a "receiver of stolen goods" who is literally called "the merry old gentleman" with heavy, dark irony. In the 1838 play adaptations, he was a straight-up caricature of evil.

Then came Lionel Bart’s 1960 musical.

Suddenly, Fagin is a showman. He’s "Reviewing the Situation." He’s almost... likable? Modern stage plays often lean into this. They treat him as a survivor in a world that hates him. You’ve probably seen him portrayed as a father figure who, yeah, teaches kids to steal, but also gives them a roof. It's a complicated shift. Actors today, like Simon Lipkin in the recent West End runs, have to balance that "loveable rogue" energy with the fact that he's still a guy who exploits orphans.

Nancy: The Heart of Every Play

Nancy is the anchor. Without her, the story is just a bunch of guys yelling in the dark. In the novel, Nancy’s backstory is bleak; she’s been a thief since she was six and likely a prostitute. The stage versions usually scrub the "prostitute" part and call her a "barmaid" at the Three Cripples.

Why She’s Different on Stage

On stage, Nancy has a belt. She sings "As Long As He Needs Me," which is basically a masterclass in toxic relationships. In Neil Bartlett’s grittier 2004 stage adaptation, Nancy is less of a musical powerhouse and more of a gritty, desperate woman trying to save a kid she barely knows.

Regardless of the version, her death is the turning point. It's the moment the "play" stops being fun. In the 1838 Royal Surrey Theatre production, this scene was so violent it reportedly caused audience members to faint.

💡 You might also like: Why The World Is Not Enough Still Divides James Bond Fans Decades Later

Bill Sikes: The Pure Villainy

Bill Sikes is the one character who rarely gets a "soft" makeover. He’s a brute. Period. In almost every adaptation, from the 19th-century melodramas to modern revivals, Bill is the shadow. He doesn't have a redemptive arc.

- The Dog: In the book and some stage plays, his dog Bull’s-eye is a mirror of his soul—abused and vicious.

- The Voice: Most stage directors cast a Bass-Baritone. You need someone who can vibrate the floorboards when he shouts.

- The End: Usually, Bill dies on the rooftops. It’s the spectacle every audience waits for.

The "Missing" Characters You Never See

If you’ve only seen the play, you’ve probably never heard of Monks. His real name is Edward Leeford, and he is Oliver’s half-brother. In the novel, he’s the real engine of the plot. He’s trying to ruin Oliver to keep an inheritance.

He's almost always cut.

Why? Because he’s complicated. He has fits, he’s mysterious, and he requires about twenty minutes of exposition that musical audiences just won't sit through. By cutting Monks, the plays make the conflict purely about Fagin and Sikes vs. Oliver. It’s simpler. It works for the stage.

Similarly, Rose Maylie is often merged with other characters or turned into "Rose Brownlow." In the book, she’s Oliver’s aunt. In the plays, she’s often just a nice lady who happens to be around when Oliver gets shot during a robbery.

The Artful Dodger and the Kids

Jack Dawkins, aka the Artful Dodger, is the life of the party. He's usually played by a teenager with way too much energy and a top hat three sizes too big. In the musical, he’s the "leader" of the gang.

But check this out: in the book, his ending is depressing. He gets caught stealing a silver snuff box and is "transported"—meaning sent to a penal colony in Australia. In the plays? He usually slips away into the night, ready for another adventure. We like our stage characters to have a bit of hope, even when the setting is a literal sewer.

🔗 Read more: Why A Dog Year Is Still The Most Honest Movie About Owning A Pet

Key Differences: Book vs. Stage

| Character | Book Persona | Stage Play Persona |

|---|---|---|

| Oliver | Often passive, a symbol of innocence. | Usually more spirited, gets a few big solos. |

| Mr. Bumble | Cruel, greedy, and truly hateful. | Often used for "comic relief" and bumbling humor. |

| Bet | A minor character, Nancy’s friend. | Often Nancy's "little sister" figure with more lines. |

| Mrs. Corney | A cold woman who lets the poor die. | Usually a flirtatious foil for Mr. Bumble. |

Actionable Takeaways for Your Next Production

If you’re studying these characters or putting on a show, don't just mimic the 1968 movie.

- Look for the grit. Even in the musical, there’s a reason these characters are desperate. If Fagin is too nice, the stakes vanish.

- Focus on the accents. The class divide between Mr. Brownlow’s "Proper English" and the gang’s "Cockney" is a character in itself.

- Don't ignore the darkness. The best versions of the Oliver Twist play characters are the ones that remember this is a story about a kid who almost starved to death.

If you want to really understand the evolution of these roles, I highly recommend reading the 1838 George Almar script. It was the first "hit" version of the story on stage, and it shows just how much Victorian audiences loved a good, bloody melodrama before we turned it into a family-friendly singalong.

Next time you see a production, watch Mr. Bumble. Is he a monster or a clown? That one choice tells you everything you need to know about the director's vision for the story.