Imagine you’re sitting in a patent office in Bern. It’s 1905. You’re twenty-six. Your name is Albert Einstein. You aren’t a "Professor" yet—you’re basically a technical expert third class. But you’ve just figured out that the entire way the world understands space and time is, well, fundamentally broken.

When people talk about on the electrodynamics of moving bodies (Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper), they usually just call it "the relativity paper." But that's a bit of a misnomer. Honestly, the title itself tells you exactly what Einstein was actually trying to fix. He wasn't trying to be a philosopher or a rebel; he was trying to solve a very specific, annoying problem in physics involving magnets and wires.

It’s wild how much we overcomplicate this.

The paper didn’t even mention the famous $E = mc^2$ equation (that came a few months later in a follow-up). Instead, it attacked a contradiction that was driving physicists crazy. On one hand, you had Newton’s mechanics, which said speeds just add up. If you throw a ball at 20 mph while standing on a train going 60 mph, the ball goes 80 mph. Simple, right? But then you had Maxwell’s equations for electromagnetism, which suggested that light always travels at one constant speed, $c$, regardless of how fast you’re moving.

You can’t have both. Einstein realized that if Maxwell was right—and he was—then our concepts of "distance" and "time" had to be the things that gave way.

Why the Aether Was the Biggest Mistake in Science

Before Einstein dropped on the electrodynamics of moving bodies, everyone believed in the "Luminiferous Aether." Scientists like Hendrik Lorentz and Henri Poincaré were convinced that just as sound needs air to travel through, light needed a medium to ripple through. They thought the Earth was literally swimming through a sea of invisible aether.

The problem? No one could find it. The Michelson-Morley experiment in 1887 tried to detect the "aether wind" and failed miserably. It was the most famous "null" result in history. Most physicists tried to patch the theory with increasingly weird explanations. Lorentz even suggested that objects physically shrink when they move through the aether.

Einstein’s genius was basically saying, "Hey, maybe the reason we can’t find the aether is because it doesn't exist."

He just tossed the whole concept out. He started with two simple postulates. First, the laws of physics are the same for everyone in uniform motion. Second, the speed of light is a constant. That’s it. Everything else—time dilation, length contraction, the loss of simultaneity—is just a logical consequence of those two rules.

The Magnet and the Conductor: The "Simple" Problem

The first half of on the electrodynamics of moving bodies deals with something called the "moving magnet and conductor problem." It sounds boring, but it’s the core of the whole thing.

In 1905, if you moved a magnet through a stationary wire coil, it created a current. If you kept the magnet still and moved the coil, it also created a current. To a casual observer, the result is the same. But the physics textbooks of the time gave two completely different mathematical explanations for these two scenarios.

Einstein hated that.

He felt that if the observable result is the same, the underlying physical explanation should be the same. This "asymmetry," as he called it, was his primary motivation. He realized that "electric" and "magnetic" fields weren't two different things, but two sides of the same coin, depending entirely on your state of motion. It was the first true "unification" in modern physics.

Time is Not a Universal Clock

This is where things get trippy.

If you’ve ever felt like a workday is dragging while a vacation flies by, you’ve experienced psychological time. But Einstein proved that physical time is also flexible. Because the speed of light is the universal speed limit, something has to "break" when two people move at different speeds. That something is time itself.

In the paper, Einstein describes how two clocks, initially synchronized, will no longer show the same time if one is moved in a closed curve back to the starting point. This is the seed of the "Twin Paradox."

"We must bear in mind that all our judgments in which time plays a part are always judgments of simultaneous events."

That quote from the paper is vital. He’s saying that "now" doesn't mean the same thing for everyone. If a star explodes in Andromeda "now," that statement is actually meaningless unless we define our relative motion. This destroyed the Newtonian idea of an "absolute" time that ticks away the same for God, for you, and for a particle in a cyclotron.

What People Get Wrong About Einstein's Process

There's a popular myth that Einstein was a lone wolf who ignored everyone. Not true.

While on the electrodynamics of moving bodies famously contains zero citations—which is absolutely insane for a scientific paper—he was deeply influenced by others. He spent years debating these ideas with his "Olympia Academy" friends in Bern, like Maurice Solovine and Conrad Habicht. He also read Ernst Mach, who criticized Newton’s ideas of absolute space.

Also, we can't ignore Mileva Marić, his first wife. While historians debate her exact mathematical contribution, Einstein’s letters to her often said "our work" or "our theory." She was a trained physicist herself, and she likely served as his primary sounding board during that frantic summer of 1905.

The Math Behind the Magic

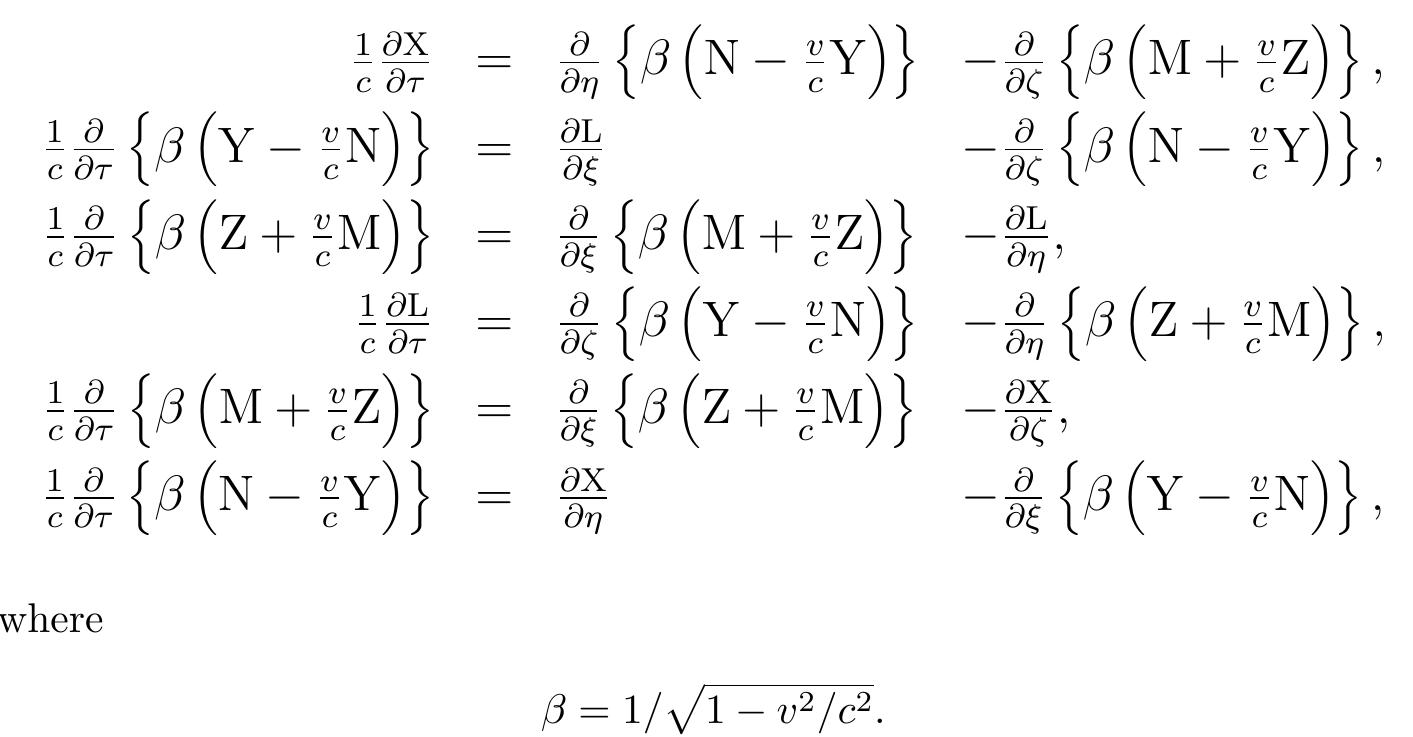

You don't need a PhD to grasp the gist, but the math is what made the paper undeniable. Einstein used the Lorentz transformations, which are a set of equations that describe how measurements of space and time change between observers.

$$t' = \gamma \left( t - \frac{vx}{c^2} \right)$$

$$x' = \gamma (x - vt)$$

Where $\gamma$ (gamma) is the Lorentz factor:

$$\gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}}}$$

As your velocity $v$ approaches the speed of light $c$, the denominator gets smaller, and $\gamma$ gets huge. This is why time slows down and objects shorten as they speed up. It’s not an optical illusion. It’s a fundamental restructuring of reality.

Why Should You Care Today?

It’s easy to think this is all just "heavy physics" that doesn't affect your life. You’d be wrong.

🔗 Read more: Windows RDP for Mac: Why Your Setup Probably Feels Laggy and How to Fix It

If we didn't account for the principles in on the electrodynamics of moving bodies, your GPS wouldn't work. The satellites for GPS move at about 14,000 km/h. Because of their speed, their internal atomic clocks tick slightly slower than clocks on Earth (special relativity). They are also higher up in a weaker gravity field, which actually makes them tick faster (general relativity, which Einstein figured out ten years later).

Engineers have to "de-synchronize" the clocks before they launch them. If they didn't, the location on your phone would be off by several kilometers within a single day. Your Uber would never find you.

Taking Action: How to Think Like 1905 Einstein

Einstein didn't find the answer by doing more experiments. He found it by "thought experiments" (Gedankenexperiments) and by questioning the most basic assumptions everyone else took for granted.

To apply this level of thinking to your own life or work, try these steps:

- Identify the Asymmetry: Look for processes in your work where the outcome is the same, but the "rules" or explanations are different. Usually, there's a simpler, unified truth hidden there.

- Challenge the "Constants": Everyone in 1905 "knew" time was absolute. What do you "know" is absolute in your industry that might actually be relative?

- Strip the Aether: What "invisible mediums" are you assuming exist? In business, this might be a "market trend" that no one can actually prove. If you remove the assumption, does the math still work?

- Read the Source: Honestly, go read a translation of the 1905 paper. It’s surprisingly readable. It’s not bogged down in jargon; it’s a masterclass in logical persuasion.

The world shifted on its axis in June 1905. Not because of a new telescope or a giant laboratory, but because one guy refused to accept a messy explanation for a moving magnet. Special relativity teaches us that the universe is far more interconnected—and far stranger—than our senses let on.

Essential Reading for Further Depth

- Subtle is the Lord by Abraham Pais (The definitive scientific biography).

- Einstein's Clocks, Poincaré's Maps by Peter Galison (Great context on the tech of the time).

- The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 2.