You've probably seen one gathering dust in a tangled bin of "old stuff" at a thrift store or maybe in your dad's garage. It’s that chunky, heavy-duty connector with the big thumb screws. Honestly, in a world where everything is USB-C or wireless, the parallel to parallel cable feels like a fossil. It’s a relic from an era when "plug and play" was more like "plug and pray for forty-five minutes."

But here’s the thing.

If you walk into a CNC machine shop, a medical imaging lab, or the back room of a legacy data center, these cables are still working hard. They aren't just old junk; they are the literal backbone of industrial hardware that was built to last thirty years instead of three. People think they’re just for old Epson printers. They’re wrong.

What is a Parallel to Parallel Cable, Actually?

Basically, it's a multi-wire cable designed to send multiple bits of data simultaneously. Think of a highway. A serial cable (like USB) is a single-lane road where cars follow each other in a line. A parallel to parallel cable is an eight-lane superhighway. Back in the 1970s and 80s, when processors were slow, sending 8 bits at once was a massive speed advantage.

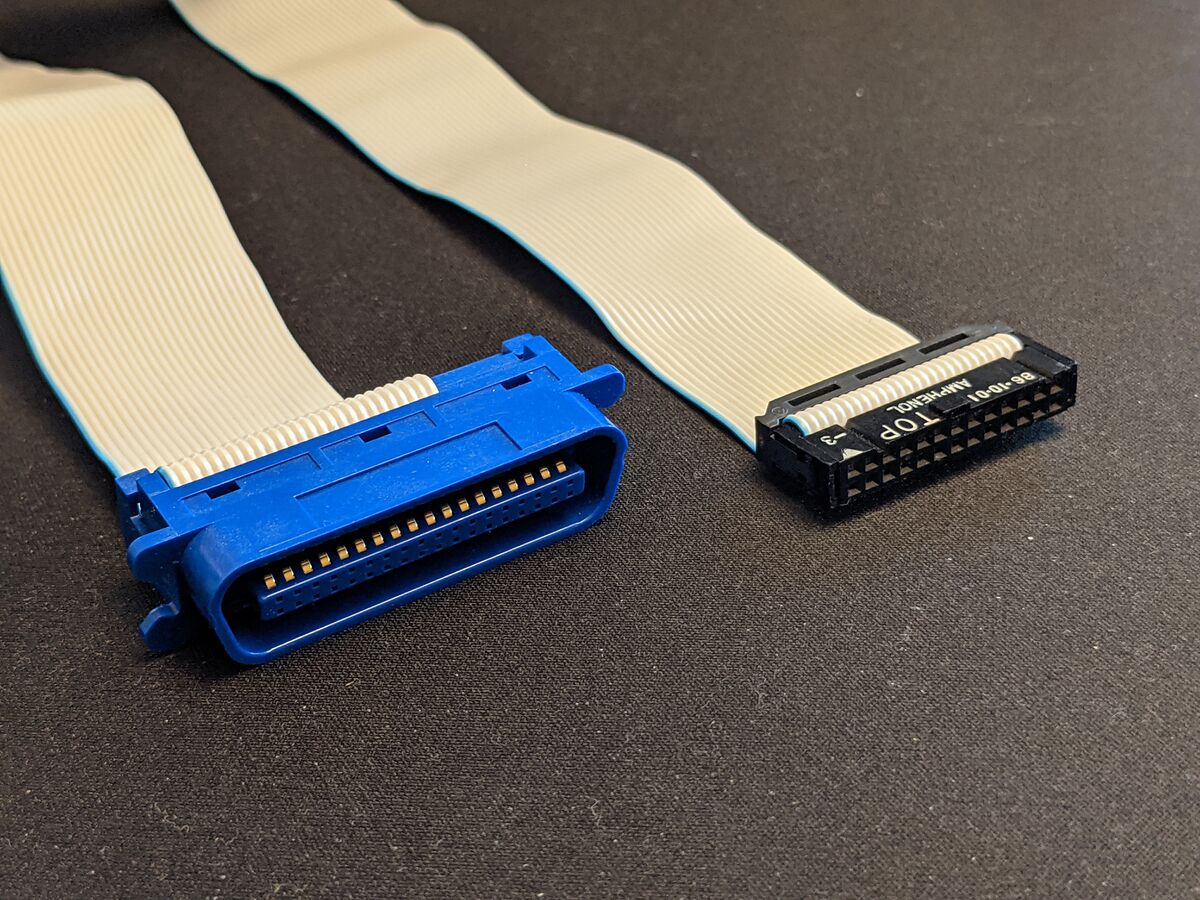

Most of these use the DB25 connector—that D-shaped housing with 25 pins. You might also hear people call them IEEE 1284 cables. That’s the official technical standard settled on by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers in 1994 to make sure different brands actually talked to each other. Before that? It was the Wild West. Centronics was the big name, but IBM eventually standardized the DB25 side on the PC.

Why We Stopped Using Them (Mostly)

Distance is the enemy.

Because you’re sending data down eight different wires at the exact same time, those signals have to arrive at the other end at the exact same moment. If the cable is too long, you get something called "crosstalk" or "signal skew." One bit arrives a microsecond late, and suddenly your print job looks like Cthulhu wrote it. USB solved this by being incredibly fast on a single path, which is much easier to manage over longer distances.

Also, they're just physically huge. You can't put a DB25 port on a MacBook Air. It would be thicker than the laptop.

The Secret Life of Parallel Cables in 2026

You’d be surprised where these things are still hiding. I recently talked to a technician who maintains older Haas CNC mills. These machines, which carve metal with terrifying precision, often rely on a parallel to parallel cable to receive instructions from a controller. Why? Because the machines cost $100,000 and the parallel port works just fine. If it isn't broken, you don't spend six figures to replace it just to get a USB port.

👉 See also: Create a Amazon account: What most people get wrong about the setup

Industrial automation is the stronghold. You’ll find them in:

- Old-school programmable logic controllers (PLCs) in factories.

- Legacy laboratory equipment like spectrometers.

- Radio broadcasting hardware where jitter must be zero.

- Retro gaming setups where enthusiasts use them for high-speed data transfer between old PCs (LapLink, anyone?).

The Bit-Banging Reality

There’s a concept in engineering called "bit-banging." It’s basically manually controlling the pins on a port via software. The parallel to parallel cable is a dream for this because you have direct access to individual pins. You can trigger a relay or read a sensor without needing a complex handshake protocol. It’s raw. It’s direct. It’s honest hardware.

Picking the Right One (It’s Not Just a Cable)

If you're actually out there looking for a parallel to parallel cable, don't just grab the cheapest one on eBay. There are different types, and they are NOT all the same.

- Straight-through cables: Pin 1 goes to Pin 1, Pin 2 to Pin 2. These are usually for connecting a computer to a switch box or certain specialized peripherals.

- Null-modem (LapLink) cables: These cross the transmit and receive lines. This is what you used in 1995 to move your Doom save files from one computer to another because you didn't have a network card.

- IEEE 1284 Compliant: This is the gold standard. These are shielded to prevent the crosstalk I mentioned earlier. If you’re running a CNC machine, get these. Don't cheap out.

Watch out for the "Printer Cable" Trap

A lot of people confuse a parallel to parallel cable with a standard printer cable. A printer cable usually has a DB25 on one end and a 36-pin Centronics connector on the other. A true parallel-to-parallel has the same connector (usually DB25 male or female) on both ends. Check your ports before you buy. Seriously. Count the holes.

Troubleshooting the "Dead" Connection

If you've got a legacy device and it isn't communicating, the cable is usually the second thing to check. The first is the BIOS/UEFI settings on your computer. Parallel ports have different modes:

- SPP (Standard Parallel Port): The slowest, one-way communication.

- EPP (Enhanced Parallel Port): Two-way, much faster.

- ECP (Extended Capabilities Port): Uses DMA to move data without bugging the CPU.

If your cable is an old, non-shielded version and your port is set to ECP, you’re going to get data corruption. It's like trying to scream through a megaphone in a tiny tiled bathroom. Dial the speed back in the settings, and suddenly, that old cable starts working again.

The Environmental Angle

We talk a lot about e-waste. Throwing away a perfectly functional $50,000 industrial lathe because you can't find a $20 parallel to parallel cable is the definition of insanity. Keeping these cables in production is actually a weird form of sustainability. It keeps heavy iron out of the scrap yard.

Actionable Steps for the Modern User

If you find yourself needing to interface with this tech today, follow this checklist to avoid a headache.

- Verify the Gender: DB25 comes in male (pins) and female (holes). Look at both the PC and the device. You might need a "gender changer" adapter, but it's better to just buy the right cable.

- Length Matters: Keep it under 10 feet if possible. If you must go longer, you absolutely need a high-quality shielded IEEE 1284 cable. 15 feet is pushing it. 25 feet is a gamble.

- Check for Bent Pins: Because these pins are exposed, they bend easily. Use a pair of tweezers to gently straighten them. If a pin snaps, the cable is toast.

- Avoid USB Adapters if Possible: USB-to-Parallel adapters are great for printers. They are often terrible for CNC machines or data transfer. They don't support "bit-banging" because the timing is off. If you need a real parallel port on a modern PC, buy a PCIe Parallel Card instead. It's a "real" hardware port that the OS treats correctly.

The parallel to parallel cable isn't going anywhere yet. It’s the survivor of the computer world—bulky, slow, but incredibly reliable when the modern stuff fails.