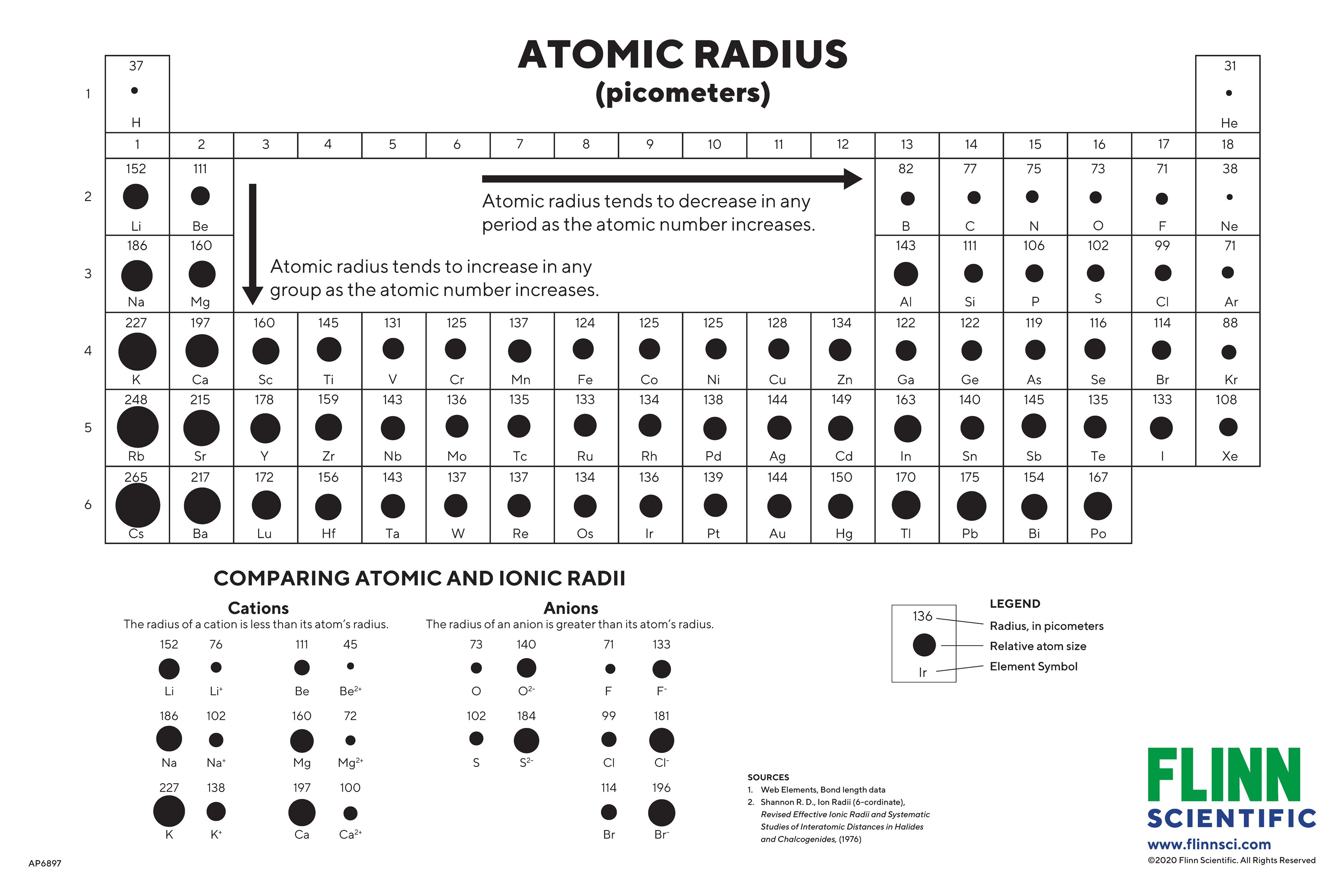

You’d think a bigger atom would, well, be bigger. It makes sense on paper. You add more protons, more neutrons, and more electrons, so the whole thing should puff out like a balloon, right? But chemistry is weird. Honestly, the way periodic table atomic sizes behave is one of the most counterintuitive things you'll ever learn in a lab. If you look at the trend moving across a single row—what scientists call a period—the atoms actually shrink.

It’s bizarre.

Imagine adding bricks to a house and the house getting smaller. That is essentially what’s happening from left to right on the chart.

The Tug-of-War Inside the Atom

To understand why this happens, we have to look at the "Effective Nuclear Charge," or $Z_{eff}$. This isn't just some textbook term; it’s the literal grip the center of the atom has on its outer edges. In the nucleus, you have protons. They are positive. Orbiting them, you have electrons, which are negative. Since opposites attract, the protons are constantly trying to pull those electrons inward.

When you move from Lithium to Neon, you're adding one proton at a time. But here’s the kicker: you’re also adding electrons to the same energy level. Because those electrons are roughly the same distance from the center, they don't really shield each other from the nucleus very well.

The result? The nucleus gets "stronger" faster than the electron cloud can push back. It’s like a magnet getting more powerful while the metal bits around it stay in the same place; eventually, they all get sucked closer to the center. This is why a Fluorine atom is significantly smaller than a Lithium atom, even though Fluorine is much heavier.

👉 See also: How to use iMovie on iPhone: What most people get wrong

The Vertical Growth Spurt

Now, if you travel down a column—a group—the logic flips back to what you'd expect. Atoms get huge. Take Cesium, for example. It’s massive compared to Hydrogen.

Why? Because every time you move down a row, you’re adding an entirely new "shell" of electrons. Think of it like putting on a bulky winter coat over a sweater. No matter how hard the nucleus pulls, that extra layer of padding creates physical distance. Plus, there’s the "Shielding Effect." All those inner electrons are essentially acting as a barrier, blocking the positive pull of the nucleus from reaching the outermost electrons.

It’s basically chaos in there. The outer electrons feel less of a "tug" and are free to drift further away, making the periodic table atomic sizes expand drastically as you move toward the bottom-left of the chart.

Why Does This Even Matter?

You might think this is just trivia for people in lab coats. It isn't. The size of an atom dictates almost everything about how it behaves in the real world.

📖 Related: Freeware Novel Writing Software: What Most People Get Wrong

- Reactivity: Smaller atoms hold onto their electrons with a death grip. This makes elements like Fluorine terrifyingly reactive because they are desperate to snatch electrons from others to fill their tiny, compact shells.

- Bonding: When atoms form molecules, their size determines bond length. This affects whether a substance is a gas, a liquid, or a solid at room temperature.

- Medicine: In pharmacology, the size of an ion (an atom that lost or gained electrons) determines if it can pass through a cell membrane. If an ion is too bulky, it’s stuck outside the "door."

The "D-Block" Contraction: A Weird Exception

If you look at the transition metals—that big block in the middle of the table—things get even messier. There’s something called the "Lanthanide Contraction."

Basically, as you hit the heavier elements like Gold or Tungsten, the $f$-orbitals come into play. These orbitals are terrible at shielding. They are shaped weirdly and don't block the nucleus’s pull effectively. Because of this, the atoms in the sixth row of the table end up being almost the same size as the atoms directly above them in the fifth row.

It's a "size plateau" that shouldn't exist, and it’s the reason why Gold is so dense. You’re packing a massive amount of mass into a tiny volume because the nucleus is pulling everything in so tightly.

Visualizing the Trend in Your Head

If you want a mental shortcut for periodic table atomic sizes, just remember the "Snowman."

Imagine a snowman tipped over. The bottom of the snowman is at the bottom-left of the table (Francium), and the tiny head is at the top-right (Helium).

- Bottom Left: The Giants. These atoms are loose, large, and lose electrons easily.

- Top Right: The Tiny Dictators. These atoms are small, tight, and hungry for electrons.

Real-World Implications of Atomic Radius

Let's talk about your phone battery. Lithium-ion batteries work because Lithium is small and light. If we tried to use Cesium—which is way further down the periodic table—the battery would have to be enormous to hold the same amount of charge. The physical size of the atom limits how much energy we can pack into a pocket-sized device.

Then there’s the world of catalysts. In car exhaust systems, we use Platinum or Palladium. The specific periodic table atomic sizes of these metals allow them to "grab" toxic gases and hold them just long enough for a chemical reaction to turn them into something less deadly. If the atoms were a fraction larger or smaller, the "fit" wouldn't work, and our air would be much dirtier.

Actionable Takeaways for Mastering Atomic Trends

Don't just memorize the chart. Understand the "why" behind it to actually use this info in a chemistry or materials science context.

- Always check the period first. If two elements are in the same row, the one further to the right is almost certainly smaller due to increased nuclear charge.

- Count the shells. If you're comparing elements in different rows, the one further down is almost always larger because of the added electron shells.

- Watch the ions. Remember that stripping an electron (making a cation) makes an atom shrink significantly because the remaining electrons feel more "pull" from the nucleus. Conversely, adding an electron (making an anion) makes it balloon out because of electron-electron repulsion.

- Use the diagonal. If you're comparing elements that are diagonal to each other (like Lithium and Magnesium), their sizes are often surprisingly similar. This is known as a "diagonal relationship" and it’s why they often behave similarly in chemical reactions.

Understanding these patterns lets you predict how elements will behave before you even put them in a beaker. It’s the closest thing to a "cheat code" for the physical sciences.