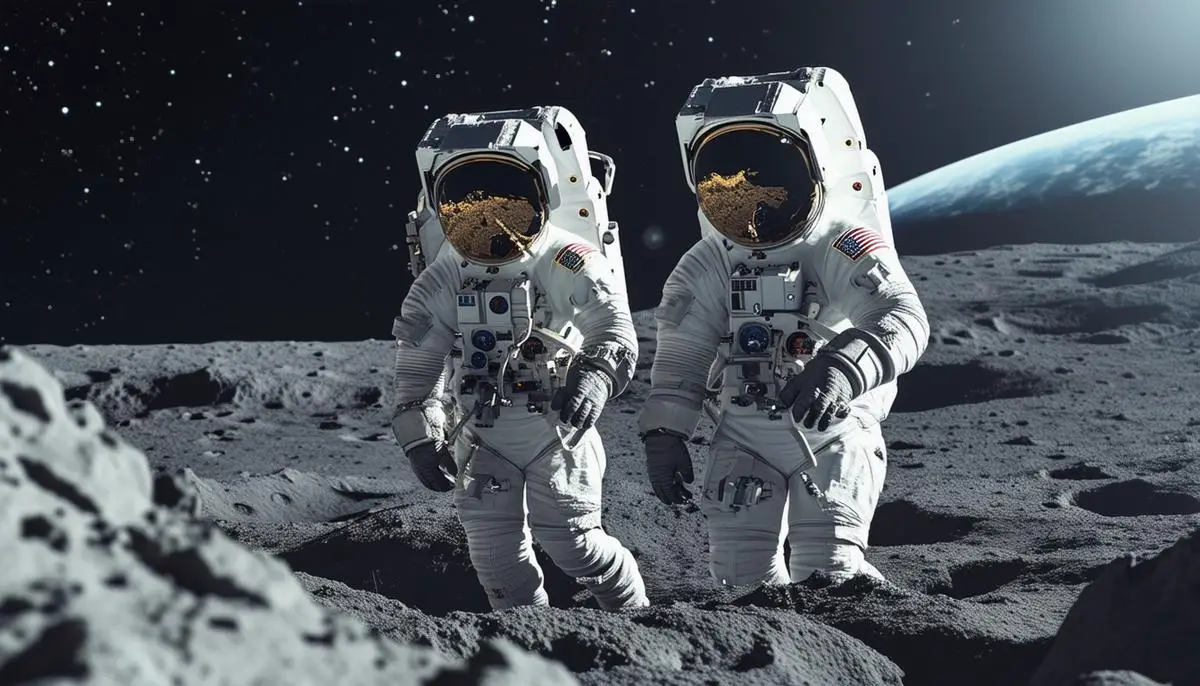

Look at that grain. That stark, harsh contrast between the blinding white of a pressurized suit and the ink-black void of the lunar sky. Honestly, it’s still the most jarring thing about photos of astronauts on the moon. People look at them today on high-res OLED screens and think they look "too perfect" or, weirdly, "too fake." But the reality of how these images were captured is a messy, technical nightmare that had nothing to do with digital filters and everything to do with a modified Hasselblad 500EL.

Neil Armstrong wasn't just a pilot. He was a cameraman. Every member of the Apollo crews had to be. They weren't just snapping selfies for the gram; they were conducting high-stakes photogrammetry under conditions that would melt a modern consumer DSLR.

The moon is a lighting disaster. You’ve got the sun—a raw, unfiltered fusion reactor—hitting highly reflective regolith (moon dust), and then you’ve got absolute shadow. There is no atmosphere to scatter light. No "golden hour." Just binary light and dark. This is why photos of astronauts on the moon often feature that strange, "theatrical" look that fuels so many conspiracy theories. But if you actually talk to someone like the late Apollo 12 astronaut Alan Bean, who later became a painter to capture those specific colors, he’d tell you the moon isn't just gray. It’s a shifting palette of browns and tans depending on the angle of the sun.

The Gear That Actually Went to the Lunar Surface

NASA didn't just grab a camera off a shelf at a hobby shop. Well, actually, they kind of did at first, but then they ripped it apart. The Hasselblad cameras were stripped of their leather coverings, mirrors, and even their viewfinders. Why? Weight. Every ounce mattered when you were trying to get off the lunar surface.

These cameras were fitted with a Réseau plate. If you’ve ever looked at photos of astronauts on the moon and noticed those tiny black crosses (+), those aren't glitches. They are etched onto a glass plate between the lens and the film. They’re called fiducial marks. Their job was to allow scientists back on Earth to calculate distances and scales in the photos. If a cross appears "behind" an object, it’s not proof of a fake; it’s a well-known phenomenon of light bleeding (halation) on high-contrast film.

Film was another beast entirely. Thin-base Kodak Ektachrome and Panatomic-X were the workhorses. The film had to survive temperature swings from 250 degrees Fahrenheit in the sun to minus 250 in the shade. That’s why the cameras were painted silver—to reflect the heat.

Why Are There No Stars in Moon Photos?

This is the big one. It’s the first thing everyone points to. "If they're in space, why is the sky black?"

💡 You might also like: Finding the Right Laptop Case 13 Inch: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s basic photography. Sunlight on the moon is incredibly bright. The astronauts are wearing bright white suits. To capture a clear image of a white suit on a brightly lit surface, you have to use a short exposure time and a small aperture. Basically, the camera's "eye" is only open for a split second. Stars are faint. To capture stars, you’d need a long exposure—several seconds at least. If Neil Armstrong had tried to take a photo that showed the stars, he and the Lunar Module would have appeared as a giant, blown-out white blob of light. You can't have both.

Basically, the moon is like a snowy day. You don't see stars during the day on Earth, even though they're still there. The sun is just washing them out. On the moon, the "daytime" lasts for two weeks, and the ground is reflecting that light right back at the lens.

The Mystery of the "Missing" Neil Armstrong Photos

Here is a weird bit of trivia: there are almost no good photos of Neil Armstrong on the moon.

Think about it. Most of the iconic shots we see—the "Visor" shot, the one of the astronaut standing by the flag—that’s Buzz Aldrin. Neil was the one holding the camera for the vast majority of the EVA (Extra-Vehicular Activity). He was the primary photographer.

There is one famous shot of Neil from the back, working at the Modular Equipment Stowage Assembly (MESA), and he appears in the reflection of Buzz's visor. That’s about it. It’s a strange historical quirk. The first man to step on the moon spent most of his time making sure the second man looked great in the photos.

Actually, there is a 16mm movie camera (the Data Acquisition Camera) that captured Neil’s first steps, but the quality is a far cry from the 70mm stills. The 70mm film used in those Hasselblads provided a resolution that even today’s 4K or 8K digital cameras struggle to match in terms of "soul" and depth.

✨ Don't miss: Beats by Dre Exercise Headphones: What Most People Get Wrong

The Cross-Hatch and the Lighting Myths

People often point to "conflicting shadow angles" in photos of astronauts on the moon as proof of multiple light sources, like a film set. But the moon isn't a flat, gray parking lot. It’s covered in craters, hills, and bumps.

- If you stand on a hill and your friend stands in a ditch, your shadows will look like they’re pointing in different directions when viewed from a 2D camera angle.

- The sun is a "point source" but the ground itself is a massive reflector.

- This "fill light" from the lunar surface illuminates the shadows.

This is why you can see details on the front of an astronaut’s suit even when they are standing in the shadow of the Lunar Module. The ground is literally acting like a giant studio reflector.

Handling the Film: The Most Stressful Job on Earth

When the Apollo 11 crew splashed down, they didn't just walk out with their rolls of film. Everything was quarantined. There was a genuine (though small) fear of "space germs." Once the film was cleared, it went to a specific lab at the Manned Spacecraft Center (now Johnson Space Center).

Photographic technician Terry Slezak was one of the first people to touch the film magazines. He actually got moon dust on his hands while opening one of the canisters—making him one of the first humans to ever touch the stuff, albeit accidentally.

👉 See also: Why Photos of Apollo 13 Still Haunt and Inspire Us Decades Later

Developing that film was a "one-shot" deal. There was no "undo" button. If the chemicals were the wrong temperature, or if a machine jammed, the visual history of the greatest human achievement would have been dissolved in a vat of acid. They ran "dummy" rolls of film through the processors for days to make sure everything was perfect before the real Apollo film touched the liquid.

How to Analyze Lunar Photos Yourself

If you’re looking at these images today, NASA has digitized most of them in ultra-high resolution through the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. It’s a rabbit hole. You can see individual scratches on the camera housings and the fine texture of the lunar soil.

When you’re looking at these, pay attention to the "halation." Because there's no atmosphere, objects don't get "fuzzier" the further away they are. On Earth, mountains look blue and hazy because of the air. On the moon, a mountain ten miles away looks just as sharp as a rock ten feet away. This lack of "atmospheric perspective" messes with our brains. It makes everything look like a miniature model.

Actionable Steps for Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into the world of Apollo photography, don't just look at the "Top 10" photos. They've been edited, cropped, and color-corrected for decades.

- Check the Raw Archives: Go to the Project Apollo Archive on Flickr. These are unprocessed scans of the original film rolls. You’ll see the "bad" shots—the blurry ones, the accidental snaps of the ground, and the lens flares. It makes the whole thing feel much more human.

- Study the Focal Lengths: Most moon photos were taken with a 60mm Biogon lens. This is a wide-to-normal lens. Understanding this helps you realize why the Earth looks so small in the distance. It wasn't a zoom lens; it was a wide-angle view of a vast, lonely landscape.

- Look for the Reflection: In almost every photo of an astronaut's gold-plated visor, you can see the photographer. It’s a fun game to trace who took what. It also shows the "workspace"—the horizon, the lander, and the equipment.

- Investigate the 16mm Footage: The still photos are great, but the 16mm DAC footage shows the movement. The way the dust falls—immediately and without drifting—is impossible to replicate in an atmosphere. It’s the ultimate proof of a vacuum.

The legacy of these images isn't just "we were there." It’s a testament to the fact that humans are, by nature, documentarians. We didn't just want to go; we wanted to show everyone else what it felt like to stand in the magnificent desolation. Those photos of astronauts on the moon are the closest we will ever get to being there ourselves until the Artemis missions put new boots on the ground and new, probably much more digital, cameras in their hands.