You’ve seen them. Those high-altitude balloon shots where the horizon looks like a perfectly leveled ruler. Maybe it was a grainy Nikon P1000 zoom video of a ship "refusing" to sink below the curve, or a stylized map of an ice wall. Pictures of flat earth are everywhere on social media, and honestly, they’re fascinating—not because they’re geographically accurate, but because of what they reveal about how we process visual data.

The human eye is easily tricked.

When you stand on a beach in Malibu or Biarritz, your brain sees a flat line. It makes sense. To our prehistoric ancestors, the world was flat for all practical purposes. If you’re building a shed or running a 10k, the curvature of the Earth doesn't matter one bit. This "local flatness" is the foundation for why pictures of flat earth feel so intuitive to some people. They align with our immediate, everyday sensory experience, even when that experience is limited by the sheer scale of the planet.

The Physics Behind Those Famous High-Altitude Photos

Most of the "proof" photos you see shared in fringe communities rely on a specific phenomenon: the limits of wide-angle lenses versus the reality of atmospheric refraction.

Take the GoPro. It’s the favorite tool of amateur balloonists. Because GoPros use a "fisheye" lens to capture a wide field of view, they distort straight lines. If the horizon is below the center of the frame, it looks curved. If it’s above the center, it looks flat or even inverted. You can find two different pictures of flat earth from the exact same flight that show completely different shapes depending on how the camera tilted in the wind.

Scientists like Neil deGrasse Tyson often point out that you have to get incredibly high—roughly 60,000 feet—before the curvature becomes undeniably obvious to the naked eye. Most commercial flights cruise at 35,000 feet. At that height, the curve is there, but it’s subtle. If you’re looking through a small, thick, multi-layered airplane window, the distortion often flattens the image.

Then there’s the "Bedford Level Experiment" style of photography. This is where people take long-distance photos of city skylines or lighthouses that should be "behind" the curve.

Why can we see the Chicago skyline from 60 miles away?

It’s called a superior mirage. It's basically a cold-weather version of the "puddle" you see on a hot highway. When cold air sits under warm air, it creates an atmospheric duct that bends light around the curve of the Earth. Joshua Nowicki famously captured a photo of Chicago from the Michigan shore, nearly 60 miles away. While some used it as one of those definitive pictures of flat earth, meteorologists at the time explained it was a "looming" mirage. The city was actually below the horizon, but its image was refracted upward.

You can tell it’s a mirage because the buildings look stretched and distorted. If the Earth were flat, you wouldn't need a specific weather condition to see the skyline; you’d see it every single day.

The Nikon P1000 and the "Bringing it Back" Myth

In the world of online forums, the Nikon P1000 is legendary. It has an 125x optical zoom. People post videos of ships disappearing hull-first, then they "zoom in" and the ship reappears. This is often cited as proof that the ship never went over a curve.

But look closer.

When you zoom in on a ship that has started to vanish, you aren't bringing it back from "behind" a curve. You are simply making a small, distant object large enough to see again. However, if you wait long enough, the bottom of the ship stays gone regardless of how much you zoom. The atmospheric haze and "mirage" effects at the water's surface often blur the bottom of the boat, making it look like it's still there when it's actually partially obscured.

📖 Related: The Truth About the TXU Power Outage Map and Why Your Lights Are Really Out

There's a reason you never see a picture of the bottom of the Statue of Liberty from the coast of Ireland. No matter how good your camera is, the physical bulk of the ocean gets in the way.

The Map Problem: Mercator vs. Reality

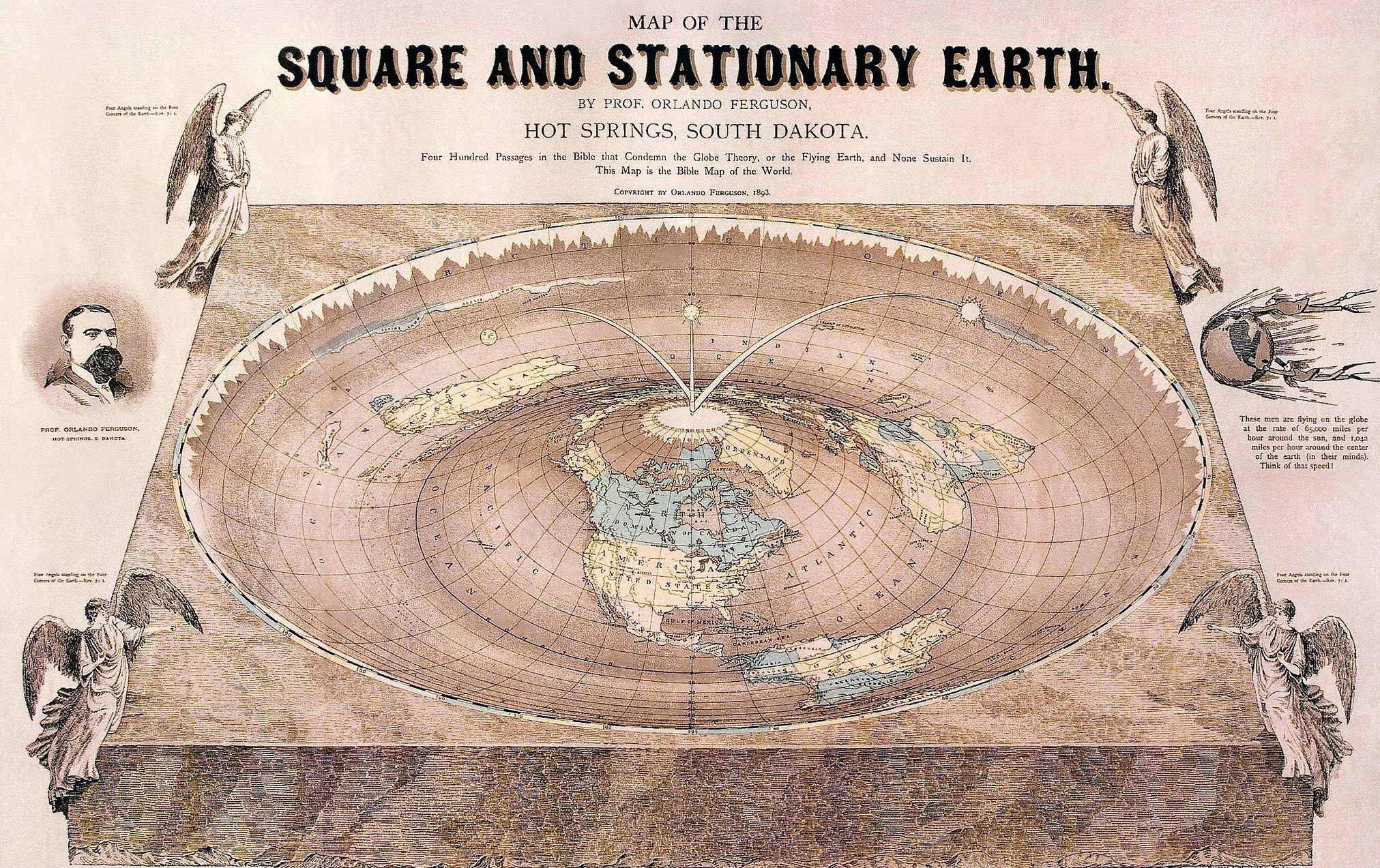

One of the most common pictures of flat earth isn't a photo at all—it's the Gleason’s Map. This is a "polar azimuthal equidistant projection." It’s a real map used by navigators and the UN, but it’s a 2D projection of a 3D sphere.

Think of it like an orange peel.

If you peel an orange and try to lay the skin flat on a table, it rips. To make it a perfect circle, you have to stretch the bottom parts (the South Pole) until they wrap all the way around the edge. This makes Australia look massive and Antarctica look like a giant ring of ice.

- In 2026, we have more satellite imagery than ever before.

- Himawari-8, a Japanese weather satellite, takes full-disk photos of Earth every 10 minutes.

- These aren't "composites" or "CGI"; they are raw data feeds used for tracking typhoons.

- The transition of shadows (the terminator line) across the planet in these photos is physically impossible on a flat plane.

Technology, CGI, and the Trust Gap

A huge reason why pictures of flat earth have gained such traction is a growing distrust in large institutions like NASA. People point to "Blue Marble" photos from different years and note that the color of the water or the size of North America looks different.

💡 You might also like: High Def Porn Clips: Why You Can’t Stop Chasing Higher Resolutions

NASA actually admits that many of their famous images are composites. Why? Because most satellites are too close to Earth to get the whole planet in one shot. They take "ribbons" of data and stitch them together like a panorama on your iPhone.

This transparency is often misinterpreted as a "confession" of faking images. But in 2015, the DSCOVR satellite was placed at the L1 Lagrangian point, about a million miles away. From there, the EPIC camera takes "single-shot" photos of the entire sunlit side of the Earth. These photos show a perfect sphere. No stitching. No CGI. Just a planet hanging in the void.

Why the "Ice Wall" Photos Aren't What They Seem

You’ve probably seen the pictures of massive, towering ice cliffs. These are often presented as the "Ice Wall" that holds the oceans in.

In reality, these are photos of the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica. It’s a massive slab of glacial ice that reaches the sea. It's hundreds of feet high, and it's definitely impressive. But it’s not a ring around the world. We have thousands of GPS-tracked scientists, explorers, and tourists who cross Antarctica every year.

If the Earth were a flat disc with an ice wall, the flight times in the Southern Hemisphere would be impossible. A flight from Perth, Australia, to Johannesburg, South Africa, would have to pass over the North Pole or take a massive detour that would last 40 hours. In reality, it’s a roughly 10-hour flight. Pilots use "Great Circle" routes, which only make sense on a globe.

Actionable Steps for Verifying Visual Data

If you want to move beyond just looking at pictures of flat earth and actually test the reality of what you're seeing, you don't need a multi-billion dollar lab. You just need a bit of patience and some basic gear.

- Check the metadata. Use an EXIF viewer on any "official" or "amateur" space photo. This will tell you the camera settings, the lens used, and often the GPS coordinates. If a photo claims to be from a balloon but has a focal length typical of a wide-angle lens, you know there’s barrel distortion involved.

- Observe the stars. If you have a friend in the Southern Hemisphere, have them take a photo of the night sky at the same time you do in the North. You will see entirely different constellations. More importantly, people in Australia, South Africa, and South America all see the same southern stars (like the Southern Cross) looking south. On a flat map, "South" is every direction away from the center, meaning they should all be looking at different things.

- The Shadow Test. Find a local tall structure—a water tower or a skyscraper. On a clear day, watch the shadow during a lunar eclipse. The shadow cast by the Earth onto the moon is always round. Only a sphere casts a round shadow from every single angle.

- Analyze the "Zoom" videos. When watching Nikon P1000 videos, look for the "cut-off" point. If the bottom of an object is missing, calculate the curvature using a standard Earth curve calculator. Account for your height above sea level. Usually, the math matches the visual perfectly once you account for refraction.

The world is a confusing place, and our eyes are designed to navigate the ground beneath our feet, not the cosmos. While pictures of flat earth might appeal to our "common sense" or our desire to question authority, they usually fall apart under the weight of basic geometry and atmospheric science. The real images of our world—the ones taken from a million miles away or recorded by weather satellites every ten minutes—show something much more complex and beautiful than a simple disc. They show a dynamic, rotating sphere that follows the same laws of physics as every other planet we can see through a telescope. Identifying the difference between a lens artifact and a physical reality is the first step in truly seeing the world for what it is.