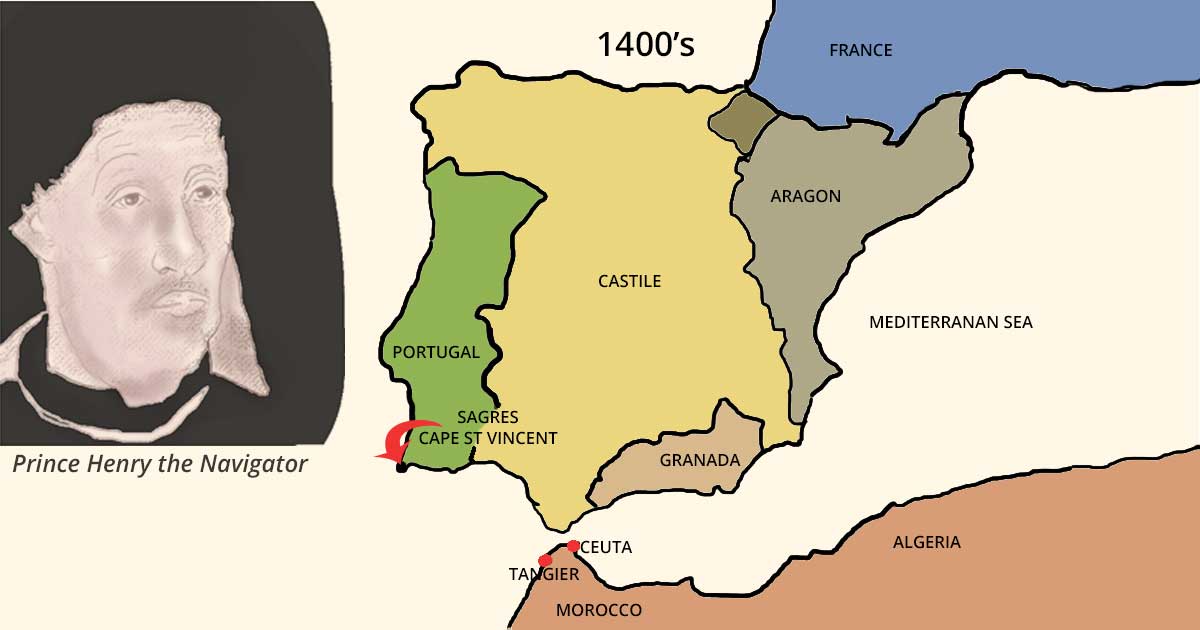

He never actually went on the voyages. That’s the first thing you have to wrap your head around when talking about Prince Henry the Navigator. It’s a bit of a historical bait-and-switch. We call him "the Navigator," but the guy spent most of his time on dry land, staring at charts or counting coins in Sagres.

He was a royal. A third son. Basically, he had a lot of ambition and just enough distance from the throne to get weird with his hobbies. Those hobbies just happened to involve rewriting the map of the known world.

📖 Related: Countries With Most Time Zones: Why France Beats Russia (And Why It's Kinda Weird)

The Myth of the School at Sagres

If you pick up an old textbook, you’ll read about this legendary "School of Navigation" Henry built on the windswept cliffs of Sagres. It sounds cinematic. You imagine a medieval NASA where salt-crusted captains and bearded cartographers whispered about the edge of the world.

The reality? It was probably more like a loose network of freelancers.

Henry was a talent scout. He used his position as the Grand Master of the Order of Christ—which, by the way, inherited the massive wealth of the Knights Templar—to fund his projects. He brought in Jewish cartographers like Jehuda Cresques and Arab mathematicians. He knew that to beat the ocean, he needed the people who actually understood it.

Why the Caravel changed everything

Before Henry, European ships were basically floating tubs. They were great for the Mediterranean, where the winds are predictable, but they were useless against the Atlantic.

Henry’s team developed the Caravel.

It was small. Fast. It used lateen (triangular) sails that allowed the ship to "tack" or sail against the wind. Without this specific piece of tech, the Age of Discovery simply doesn't happen. You can’t just sail down the coast of Africa if you can’t figure out how to sail back up against the prevailing winds. Henry figured out that engineering was the key to empire.

The Gil Eanes Breakthrough

For decades, the world ended at Cape Bojador.

Sailors called it the "Sea of Darkness." They genuinely believed the water boiled there or that the currents would suck a ship into a permanent abyss. It wasn't just superstition; it was a physical barrier. Between 1424 and 1433, Henry sent fifteen expeditions to pass the Cape.

All fifteen failed.

The captains would get close, see the terrifying breakers and the red sands of the Sahara blowing into the sea, and turn around. They’d tell Henry the "monsters" were too big.

In 1434, a guy named Gil Eanes finally did it. He sailed out into the open ocean, looped around the Cape, and found... nothing. Just more sea. This was the "Moon landing" moment of the 15th century. It proved that the ocean was a highway, not a wall.

The Dark Side: Slavery and Gold

We can't talk about Prince Henry the Navigator as if he was just some curious scientist. He was a businessman and a crusader. The Portuguese weren't just looking for knowledge; they were looking for a way to bypass the Saharan trade routes controlled by Muslim states.

They wanted gold. And they found people.

💡 You might also like: The Weather in Long Beach California Explained (Simply)

In 1441, Antão Gonçalves brought the first African captives back to Portugal. Henry didn’t just tolerate this; he saw it as a revenue stream. By 1444, the first large-scale slave auction happened in Lagos, Portugal. Henry was there. He took his "royal fifth" of the profits.

History is messy like that. The same man who pushed the boundaries of human geography also laid the groundwork for the Atlantic slave trade. You can't separate the two. He wanted to find "Prester John"—a mythical Christian king in Africa—to form an alliance against Islam, but what he actually found was a lucrative system of human trafficking that would reshape the globe for four hundred years.

Science over Superstition

What makes Henry an "explorer" in spirit, if not in practice, was his obsession with data.

Before him, maps were mostly "Mappa Mundi"—theological drawings where Jerusalem was the center of the world and monsters lived in the corners. Henry insisted on portolan charts. These were practical. They were based on actual sightings, compass bearings, and distances.

He forced his captains to keep rigorous logs. If you saw a new bird, you wrote it down. If the water changed color, you noted the depth.

- The Compass: Refined for use in the Southern Hemisphere.

- The Astrolabe: Adapted from Islamic scholars to determine latitude by the stars.

- The Volta do Mar: A sailing technique where you actually sail away from your destination to catch a circular wind that brings you home.

It was basically the birth of the scientific method applied to the horizon.

Henry’s True Legacy in 2026

If you visit the Algarve today, you can stand on the point at Sagres. It’s brutal. The wind feels like it wants to throw you off the continent. It’s easy to see why someone sitting there would become obsessed with what lay beyond the mist.

Henry died in 1460. He was heavily in debt. He never saw Vasco da Gama reach India or Columbus hit the Americas. But he was the one who turned the key. He moved the center of gravity from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic.

He wasn't a nice guy. He wasn't even a "navigator" by the literal definition. But he was the first person to treat exploration like a corporate R&D project.

How to Explore Like Henry (The Modern Version)

If you're looking to channel that 15th-century energy into your own life or travels, stop looking at the "top ten" lists.

- Invest in the tech. Henry didn't go cheap on ships. If you're hiking, get the GPS. If you're diving, get the gear. Don't let bad equipment limit your radius.

- Hire the "heretics." Henry succeeded because he worked with people the Church didn't like. Seek out perspectives that contradict your "known world."

- The Gil Eanes Rule. Most "dead ends" in your life are just Cape Bojadors. They are psychological barriers, not physical ones. Sail a bit further out into the deep water to see if the "monsters" are real.

- Document everything. Data is the only thing that turns a trip into an expedition.

Prince Henry the Navigator changed the world by staying home and obsessing over the details. He proved that you don't need to hold the rudder to steer the course of history. You just need the map, the money, and the guts to ignore the people saying the water is boiling.