You probably remember sitting in a stuffy middle school classroom, staring at a chalkboard while a teacher droned on about René Descartes. Maybe you were bored. Honestly, most people were. But that simple grid—the Cartesian plane—is basically the secret language of everything from the GPS in your pocket to the physics engine in Call of Duty. When we talk about quadrants on a graph, we aren't just talking about math homework. We are talking about how humans map reality.

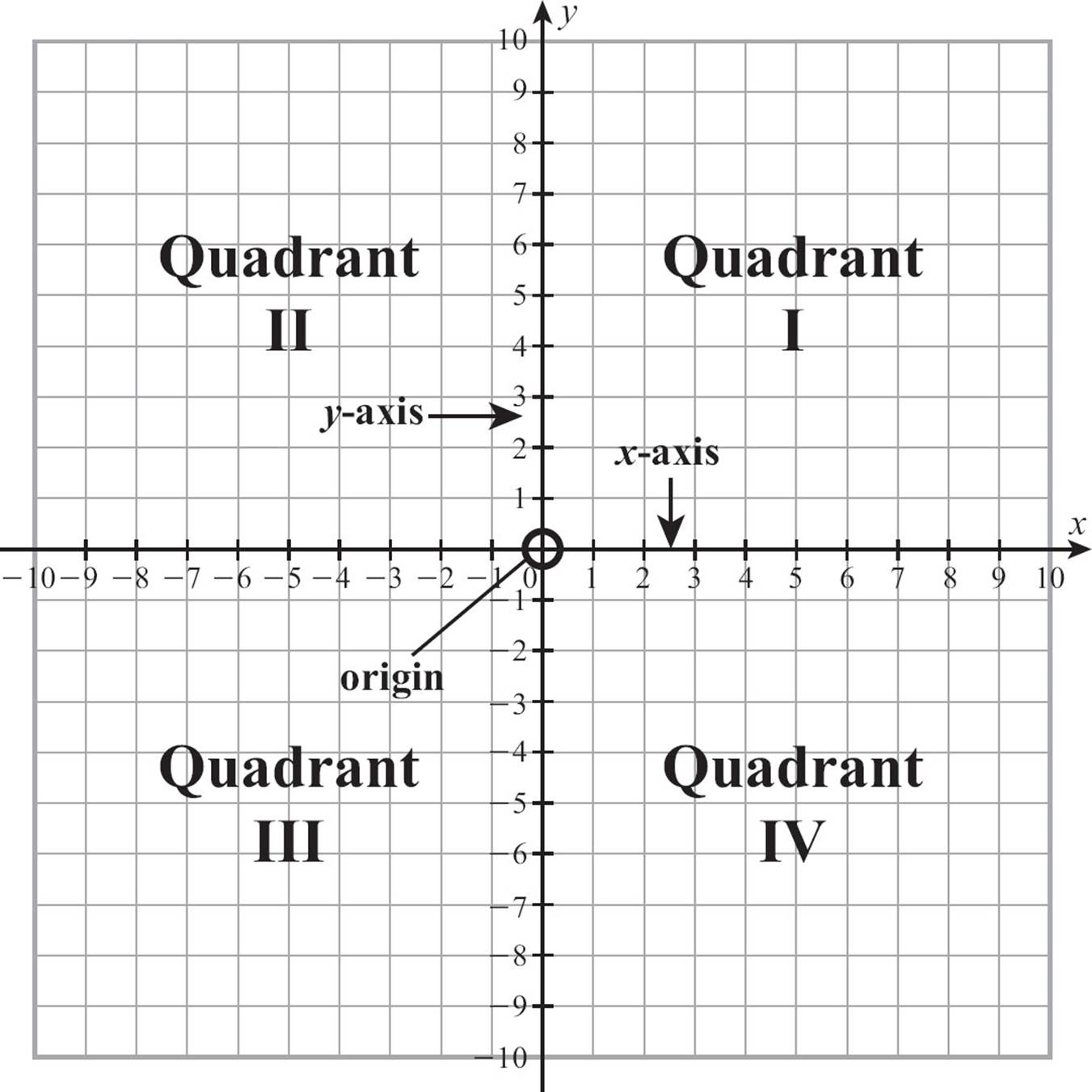

It's a cross. Two lines. One horizontal, the x-axis. One vertical, the y-axis. They meet at a center point called the origin, which is $(0,0)$ in coordinate geometry. This intersection carves the world into four distinct zones. These are the quadrants. We number them I, II, III, and IV, moving counter-clockwise. Why counter-clockwise? It feels weird, right? It’s because of how angles are measured in trigonometry, starting from the positive x-axis and rotating up.

If you get the signs wrong, your data is garbage. It’s that simple.

The Four Zones and Their Secret Identities

Quadrant I is the happy place. Everything is positive here. If you’re looking at a company’s profit margins over time and the data is sitting in the top-right, things are going great. In this zone, $x > 0$ and $y > 0$. It’s the most common quadrant used in basic business analytics because we rarely want to talk about "negative time" or "negative products sold." But life isn't always positive.

Then you move left. Quadrant II is where things get interesting. Here, $x$ is negative, but $y$ stays positive. Think about a car reversing but still gaining altitude as it goes up a hill. In a mathematical sense, this is where you’ll find angles between $90$ and $180$ degrees. It’s the "upper left" of your mental map.

The Low Points: Quadrants III and IV

Quadrant III is the basement. Both $x$ and $y$ are negative. $( - , - )$. If you’re a pilot and you’re seeing these numbers, you might be in trouble, or at least heading in a very specific downward-and-backward direction. In economics, this quadrant is often used to model total losses or "negative growth" scenarios where both investment and return are in the red.

Finally, there’s Quadrant IV in the bottom right. Here, $x$ is positive but $y$ is negative. Imagine you’re moving forward in time (positive $x$) but your bank account balance is dropping (negative $y$). It's a common sight in "burn rate" charts for tech startups.

Real-World Chaos and Coordinate Geometry

We often think of these quadrants as static boxes on graph paper. They aren't. In the real world, the quadrants on a graph represent physical space. Take civil engineering. If you're using a Total Station to survey a piece of land, you’re basically living in these quadrants. If you misidentify a coordinate in Quadrant III as being in Quadrant IV, you might end up trying to build a bridge pier in the middle of a river instead of on the bank.

There’s also the psychological aspect. Have you ever seen the Eisenhower Matrix? It's a productivity tool that uses the quadrant system to rank tasks by urgency and importance.

- Quadrant 1: Urgent and Important (Firefighting mode).

- Quadrant 2: Not Urgent but Important (The "sweet spot" for growth).

- Quadrant 3: Urgent but Not Important (The interruption zone).

- Quadrant 4: Neither (The time-waster).

It’s funny how a 17th-century mathematical concept perfectly describes why you spent three hours answering emails instead of writing your book.

Common Blunders Even Pros Make

People mix up the axes. All the time. The x-axis is "abscissa" and the y-axis is "ordinate." Those are fancy words for "side-to-side" and "up-and-down."

One huge mistake in data visualization is ignoring the origin. If you don't start your y-axis at zero, you can make a tiny change look like a mountain. But if you're plotting data across different quadrants, the origin $(0,0)$ is your anchor. Without it, the "negative" space loses its meaning. You can’t show a deficit if you don't show where "zero" is.

📖 Related: Elon Musk Twitter Meeting Employee Reactions: What Really Happened

Another thing? The labeling. It's almost a universal rule to use Roman Numerals (I, II, III, IV). Using standard digits like 1, 2, 3, 4 isn't "wrong" in a legal sense, but it’ll get you some side-eye from math purists and engineers. It’s about tradition, sure, but it also helps distinguish quadrant numbers from the actual data points on the scale.

The Tech Behind the Grid

In computer graphics, things get weird. Most screen coordinate systems actually put $(0,0)$ in the top-left corner. As you move down the screen, the $y$ value actually increases. This is the opposite of the standard Cartesian quadrants we learn in school. Why? It’s a carryover from how old CRT monitors used to "scan" lines of pixels from top to bottom.

If you are a developer or a gamer, you are constantly translating between "Screen Space" and "World Space." In World Space, you use the standard quadrants. In Screen Space, you’re basically upside down. If you don't understand how these quadrants on a graph flip and rotate, your character will be looking at the ground when they should be looking at the sky.

Navigating the Logic

Think about the unit circle. It’s the holy grail of trigonometry.

- In Quadrant I, all trig functions (Sine, Cosine, Tangent) are positive.

- In Quadrant II, only Sine is positive.

- In Quadrant III, only Tangent is positive.

- In Quadrant IV, only Cosine is positive.

Teachers use the mnemonic "All Students Take Calculus" to remember this. It's a bit cliché, but it works. If you're calculating the trajectory of a projectile, knowing which quadrant your angle falls into tells you immediately if your object is moving up, down, left, or right before you even finish the math.

Practical Steps for Mastering the Grid

Don't just look at the lines. Understand the movement.

- Check your signs first. Before you plot a single point, look at your $(x, y)$ coordinates. If you see a negative $x$, move left. If you see a negative $y$, move down. It sounds simple, but under pressure, people flip them.

- Define your origin. In business data, $(0,0)$ might represent today's date and current revenue. Anything to the left is history; anything to the right is a projection.

- Use consistent scales. If one "unit" on the x-axis represents a mile and one "unit" on the y-axis represents an inch, your quadrants will look distorted. This is called "aspect ratio distortion" and it's a leading cause of misleading charts.

- Label the quadrants for clarity. If you are presenting to a non-technical audience, don't assume they know what Quadrant III means. Literally write "Losses/Past Data" in that section of the graph.

The Cartesian system changed how we see the world by merging algebra with geometry. It gave us a way to describe "where" something is using only numbers. Whether you're mapping the stars or just trying to figure out why your company's expenses are spiking, those four little boxes are the most powerful tools in your toolkit. Use them precisely.