You've probably been there. You're building a system that needs to handle tasks in order, and you immediately reach for an ArrayList. It’s the comfort food of Java collections. But then things get messy. You're removing items from the front, shifting every other element over, and watching your performance tank as the list grows. Honestly, that's exactly why the queue interface in java exists. It isn't just another box to check in the Collections Framework; it’s a specific contract for "First-In, First-Out" (FIFO) operations that keeps your code from becoming a tangled mess of index management.

The logic behind the queue interface in java

Think of a literal queue at a coffee shop. You don't jump to the middle. You don't leave from the back unless something goes wrong. You wait your turn. In Java, java.util.Queue extends Collection, but it adds a very specific set of behaviors. It’s designed to hold elements prior to processing.

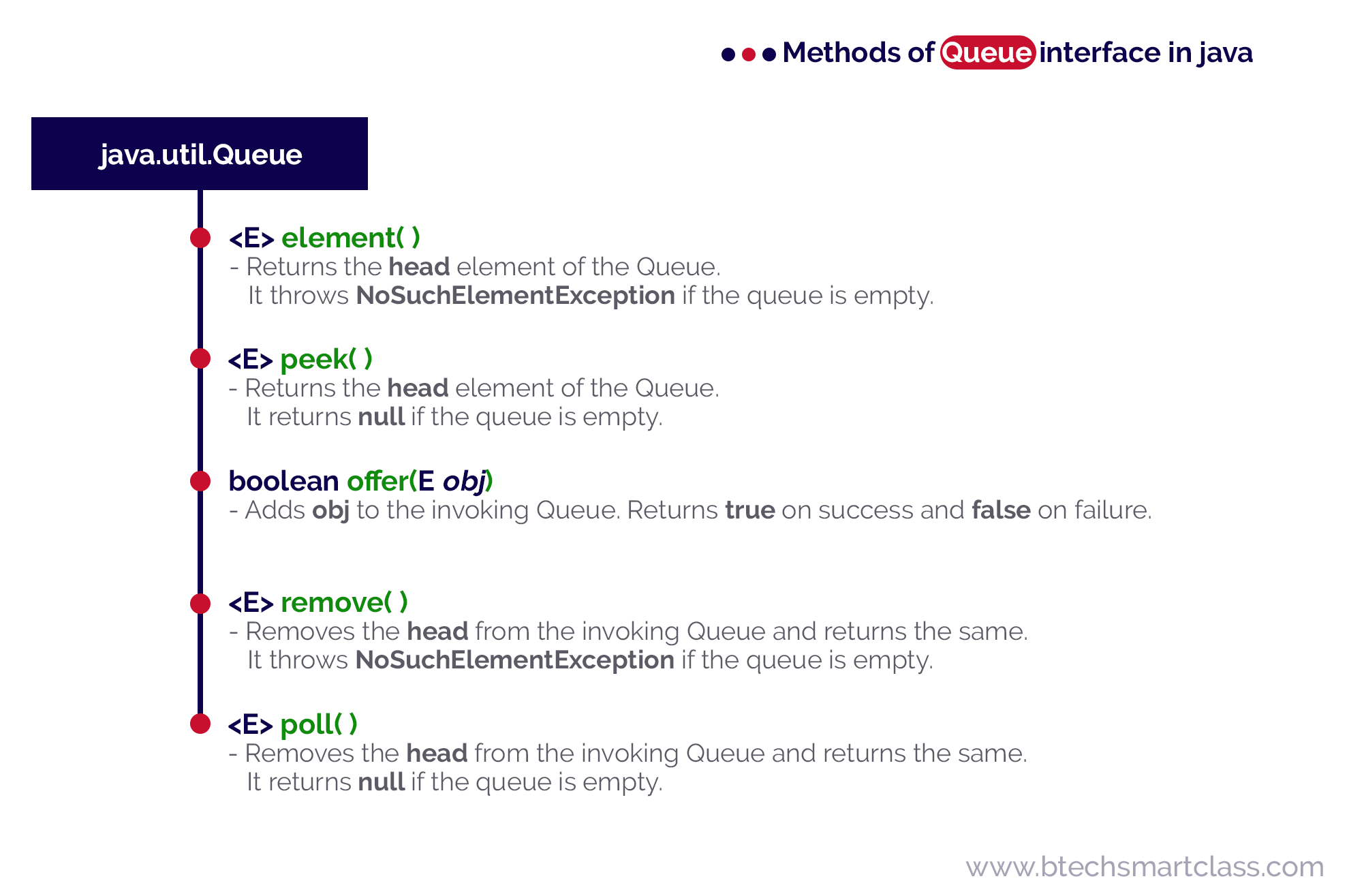

The API is actually split into two "personalities" for every operation. One set throws an exception if the operation fails—like trying to grab an item from an empty list—while the other returns a special value like null or false. Most seniors I know prefer the latter because handling NoSuchElementException is a pain in the neck when you can just check for null.

The "Exception" vs "Value" Split

If you use add(e), and the queue is full (which happens in capacity-restricted queues), it screams at you with an IllegalStateException. Use offer(e) instead. It just returns false. It’s much more chill. Same goes for remove() vs poll(). If the queue is empty, remove() blows up. poll() just gives you a null. Always use poll() unless you're absolutely certain the queue shouldn't be empty and a failure there represents a catastrophic system state.

Then there’s the inspection part. element() vs peek(). They both let you see the head of the queue without actually taking it out. Again, peek() is the safer bet for most logic because it returns null if the queue is bone dry.

The implementations that actually matter

The interface itself is just a blueprint. You can't instantiate it. You have to pick a concrete class, and this is where most people get tripped up.

LinkedList is the one everyone knows. It implements both List and Queue. It's great because it's flexible, but it's also a memory hog. Every single element is wrapped in a "Node" object with pointers to the next and previous items. If you have millions of objects, those pointers add up.

ArrayDeque is the sleeper hit. Honestly, if you don't need thread safety and you don't need to null-check (it doesn't allow nulls), you should probably be using ArrayDeque instead of LinkedList. It's backed by a circular array. It's faster. It's more cache-friendly. Joshua Bloch, the guy who basically wrote the Java Collections Framework, has been on record saying ArrayDeque is generally better than Stack and LinkedList for most queue/stack needs.

PriorityQueue is the weird cousin. It doesn't follow the FIFO rule. Instead, it orders elements based on their natural ordering or a custom Comparator. If you put a "5", a "1", and a "10" into a PriorityQueue, the first thing you poll() will be "1". It’s essentially a heap. It’s incredibly useful for things like Dijkstra’s algorithm or any task-scheduling where some jobs are just more important than others.

📖 Related: Find People by Photo: Why It’s Harder (and Weirder) Than You Think

Concurrency: Where things get spicy

If you're working in a multi-threaded environment—which is almost everyone these days—the standard Queue implementations will break. They aren't thread-safe. You’ll end up with race conditions where two threads try to poll the same item, and your data gets corrupted.

This is where BlockingQueue comes in. It lives in java.util.concurrent.

- ArrayBlockingQueue: It has a fixed size. If it's full, a thread trying to add something will literally wait (block) until space opens up.

- LinkedBlockingQueue: Can be optionally bounded. It’s the backbone of most

ThreadPoolExecutorsetups. - SynchronousQueue: This one is wild. It has a capacity of zero. Yes, zero. A thread trying to put an item in must wait until another thread is ready to take it. It’s a direct hand-off.

Doug Lea, the concurrency wizard behind the java.util.concurrent package, designed these to handle the producer-consumer pattern without you having to write a single wait() or notify() call. It saves lives. Or at least, it saves weekends.

Common pitfalls to avoid

Don't use null as an element. Just don't. Most implementations, like ArrayDeque and PriorityQueue, will throw a NullPointerException if you try. Even in LinkedList where it is technically allowed, it makes your poll() checks ambiguous. Was the queue empty, or was the item just null? It’s a bad habit.

Another big mistake is using size() to check if a queue is empty in a loop. In some concurrent queues, size() is an $O(n)$ operation because it has to traverse the whole thing to count. Always use isEmpty(). It’s faster and more intent-revealing.

Performance Reality Check

| Operation | LinkedList | ArrayDeque | PriorityQueue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Offer (Insert) | $O(1)$ | $O(1)$ amortized | $O(\log n)$ |

| Poll (Remove) | $O(1)$ | $O(1)$ | $O(\log n)$ |

| Peek | $O(1)$ | $O(1)$ | $O(1)$ |

Practical usage: A real-world scenario

Imagine you're building a log processing system. Logs are coming in hot from five different microservices. You can't write them to the database fast enough. If you use a simple ArrayList, you'll have to synchronize access, which creates a bottleneck.

Instead, you use a LinkedBlockingQueue. The microservices (producers) call offer(). If the database is lagging and the queue hits its limit, the services can choose to drop the log or wait. The database writer (consumer) sits in a loop calling take(). This method blocks until a log is available, so it's not wasting CPU cycles spinning around an empty list.

// Simplified producer-consumer snippet

BlockingQueue<String> logQueue = new LinkedBlockingQueue<>(1000);

// Producer thread

logQueue.offer("Error: User not found");

// Consumer thread

String log = logQueue.take(); // Waits here until something exists

saveToDb(log);

Why the Queue interface in java matters for your career

Understanding the queue interface in java is a litmus test for "junior vs senior" developers. Juniors use List for everything. Seniors understand the nuances of data structures. They know that a PriorityQueue can replace a complex sorting logic, and an ArrayDeque can significantly reduce the memory footprint of a high-throughput application.

When you're designing systems, think about the flow of data. Is it a stream? Is it a buffer? If the answer is yes, you're looking for a queue.

Next steps for mastering Java Queues:

- Refactor an old project: Look for places where you used a

Listbut only ever added to the end and removed from the front. Swap it for anArrayDequeand run a quick benchmark. - Explore the Deque interface: Queues are one-way. Deques (Double-Ended Queues) allow you to add and remove from both ends. It’s the secret behind building efficient undo/redo functionality.

- Study PriorityQueue Comparators: Try implementing a

PriorityQueuewhere the priority changes dynamically based on an object's internal state. It’s a common interview challenge and great for internalizing how heaps work. - Deep dive into TransferQueue: If you're doing heavy-duty concurrent programming, look at

LinkedTransferQueue. It’s a hybrid ofLinkedBlockingQueueandSynchronousQueuethat offers even more control over data hand-offs between threads.