You’re sitting at a rural intersection, idling. The engine hums. Suddenly, a bell clangs—that sharp, rhythmic metal-on-metal sound—and those red railroad crossing gate lights start their frantic, alternating dance. It’s a scene played out thousands of times a day across the country, yet most of us just see them as a minor annoyance, a signal to check our watches and hope it isn’t a mile-long coal drag. But there’s a massive amount of engineering shoved into those little glowing orbs. They aren't just "on" or "off." They represent a century of trial, error, and some surprisingly intense physics.

Basically, if these lights fail, people die. That’s the high-stakes reality for companies like Siemens Mobility or Wabtec when they design these systems. It’s not just about a bright bulb; it’s about visibility under the worst possible conditions, from blinding Midwestern blizzards to the hazy, humid heat of a Louisiana summer.

The Shift From Incandescent to LED (and the "Phantom" Problem)

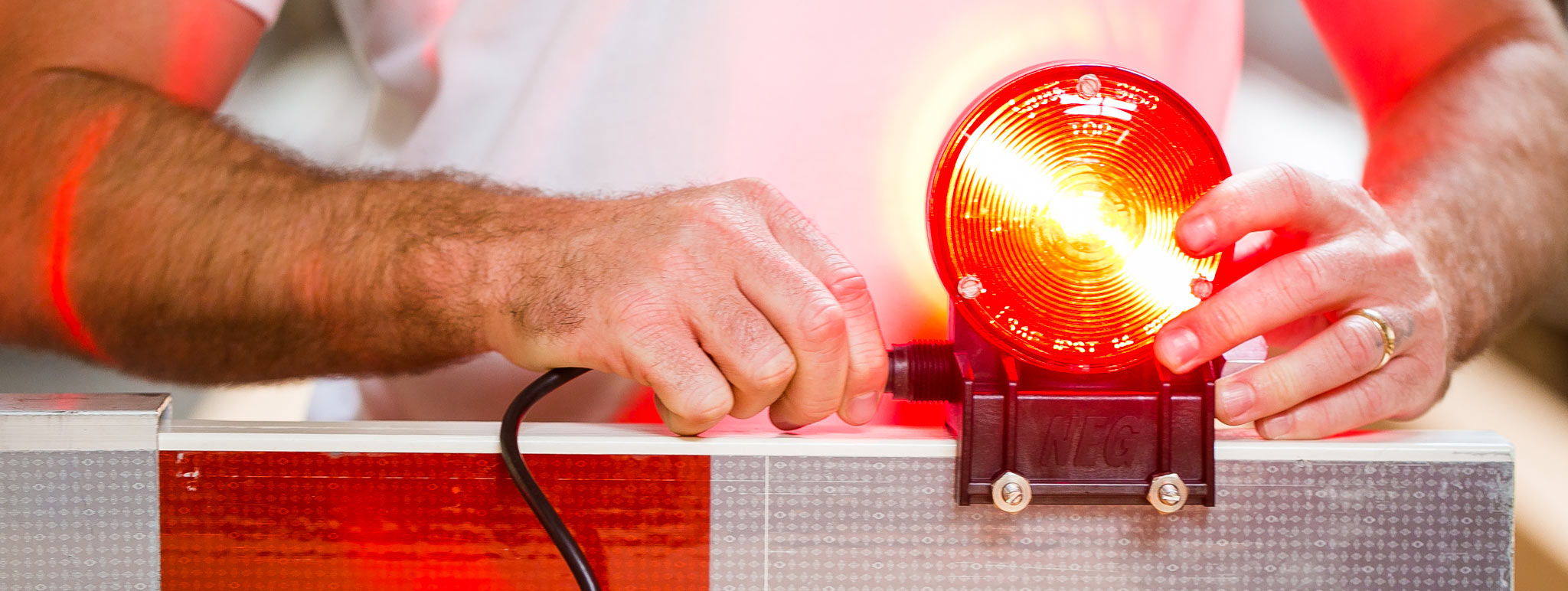

For decades, railroad crossing gate lights relied on specialized incandescent bulbs. These weren't your average living room lamps. They were ruggedized, vibration-resistant filaments designed to survive the literal ground-shaking force of a passing freight train. But they had a flaw. They burned out. A dead bulb at a crossing is a massive liability, which is why the industry has almost entirely pivoted to Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs).

LEDs changed the game. They last longer, use way less power, and—critically—they reach full brightness instantly. No "warm-up" like the old vacuum tubes. But here’s something most people don't know: the early switch to LEDs caused a weird safety issue called "sun phantom."

Because LEDs are often behind a clear or slightly tinted lens, sunlight can hit the reflective backing of the light housing and bounce back out. To a driver, it looks like the light is on when it’s actually off. Engineers had to get creative. They started using "long hoods" or visors, and specific internal geometries, to make sure that a "dark" signal stays dark even when the sun is at a low angle. If you ever see a gate light with an unusually deep black cowl around it, that’s why. It's fighting the sun.

How the Gate Lights Actually Talk to the Signal House

The lights on the gate arm itself are usually wired in a specific sequence. Have you ever noticed that they don't all blink at once? Usually, the one at the very tip of the arm stays solid, while the two closer to the pivot point alternate. This isn't just for flair.

- The tip light stays constant to mark the literal end of the obstruction. If you’re a driver in the dark, you need to know exactly how far that arm extends across the lane.

- The alternating lights provide the "movement" that triggers the human brain’s "danger" response. Our eyes are evolved to notice flickering or moving light much faster than a steady glow.

The power for these comes from a battery backup system housed in that silver or grey bungalow you see near the tracks. This is non-negotiable. If the local power grid goes down during a storm, those railroad crossing gate lights have to keep swinging for at least several hours, sometimes days, depending on the Department of Transportation (DOT) regs for that specific corridor. They run on DC power—usually 12 volts—which makes them compatible with massive lead-acid or nickel-cadmium battery arrays.

Physics of the Lens: Why Red is Non-Negotiable

Why red? It seems obvious because red means stop. But there’s a deeper, scientific reason involving "Rayleigh scattering." Red light has a longer wavelength. In foggy or smoky conditions, longer wavelengths aren't scattered as easily by particles in the air compared to blue or violet light. Red cuts through the junk.

The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) has incredibly strict standards for the "chromaticity" of these lights. It can't just be "sorta red." It has to fall within a very specific coordinate on the color spectrum to ensure that color-blind drivers (who can usually still distinguish the intensity and position) and those in heavy rain get the exact same message.

The lenses themselves aren't just flat glass. If you look closely at a modern 12-inch LED signal, you’ll see a complex pattern of "fresnel" ridges. These ridges take the light from the small LED chips and spread it into a wide, horizontal beam. This ensures that a trucker sitting high up in a cab and a driver in a low-slung sports car both see the same brightness.

👉 See also: The Keyword Collapse: Why "Keywordese" Finally Died in 2026

Maintenance: The Job No One Envies

Maintaining railroad crossing gate lights is a grueling, 24/7 job. Signal maintainers are the unsung heroes here. They have to perform "monthly" and "quarterly" inspections mandated by federal law. This involves:

- Checking the "alignment." If a gate gets bumped by a wind gust or a reckless driver, the light might be pointing three degrees too high. To a driver 500 feet away, that makes the light look dim or invisible.

- Voltage testing. They have to ensure the "drop" isn't too significant across the length of the gate arm.

- Cleaning. Road salt, grime, and spider webs can reduce light output by 50% over a single winter.

Honestly, the tech is getting even weirder. Some newer systems include "health monitoring." This allows the signal to send a digital ping back to a central dispatch center if a single string of LEDs fails. Instead of waiting for a citizen to call and say "the light looks dim," the system basically calls for its own doctor.

Addressing the Common "Malfunction" Myths

People often think that if the gates are down and the lights are flashing but no train is coming, the system is "broken." Usually, it's the opposite. It’s working exactly as designed.

📖 Related: Threatening text messages from unknown number: What you need to do right now

Most crossings use "track circuits." A train's metal wheels complete an electrical circuit between the two rails. If there’s a break in the rail, or if some debris creates a "shunt," the system fails into "safe mode." In the world of railroad crossing gate lights, "safe" means the lights flash and the gates drop. It’s better to annoy a hundred drivers with a false alarm than to have a train blast through a crossing with dark signals.

Actionable Steps for Drivers and Property Owners

If you encounter a crossing where the lights are dim, broken, or misaligned, don't just drive around the gates. That's a felony in many spots and a death wish in all of them.

- Locate the Blue Sign: Every single public crossing in the United States has a small blue sign (the ENS sign). It lists a 1-800 number and a unique DOT crossing number (e.g., 123 456X).

- Call it In: This doesn't go to 911; it goes directly to the railroad's dispatchers. They can stop trains immediately via radio while they send a maintainer to fix a flickering light.

- Check the Lens: If you are a private property owner with a "farm crossing," you are often responsible for keeping the brush cleared. A $5,000 LED signal system is useless if a willow tree is blocking the line of sight.

- Respect the "15-Second Rule": Most gates are timed so that the railroad crossing gate lights begin flashing at least 20 seconds before the train arrives. If you see the lights, the train is closer than it looks. Trains are massive; your brain struggles to accurately judge the speed of large objects.

The system is a masterpiece of redundant, "fail-safe" technology. From the specific wavelength of the red LED to the battery backups in the silver bungalow, every piece exists to solve a problem discovered over 150 years of railroading. Next time you're stuck at a crossing, take a second to look at the pattern of those lights. It’s a lot more than just a red bulb.

Next Steps for Safety Compliance:

If you manage a facility with private rail spurs, conduct a "nighttime visibility audit" once every six months. Stand 250 feet back from your crossing and verify that the red lights are not just visible, but "arresting" to the eye. If they look washed out by nearby streetlights, consider installing high-contrast backplates to improve the signal-to-noise ratio for drivers.