In 1991, a math doctoral candidate walked into a meeting with a small-time publisher named Peter Adkison. He wasn't there to pitch a card game. He wanted to sell a board game about robots racing through a factory called RoboRally. Adkison liked the game, but he was blunt: Wizards of the Coast was basically broke. They couldn't afford the printers or the boxes for a board game. What they needed was something portable, something people could play in line at a convention while waiting for a demo.

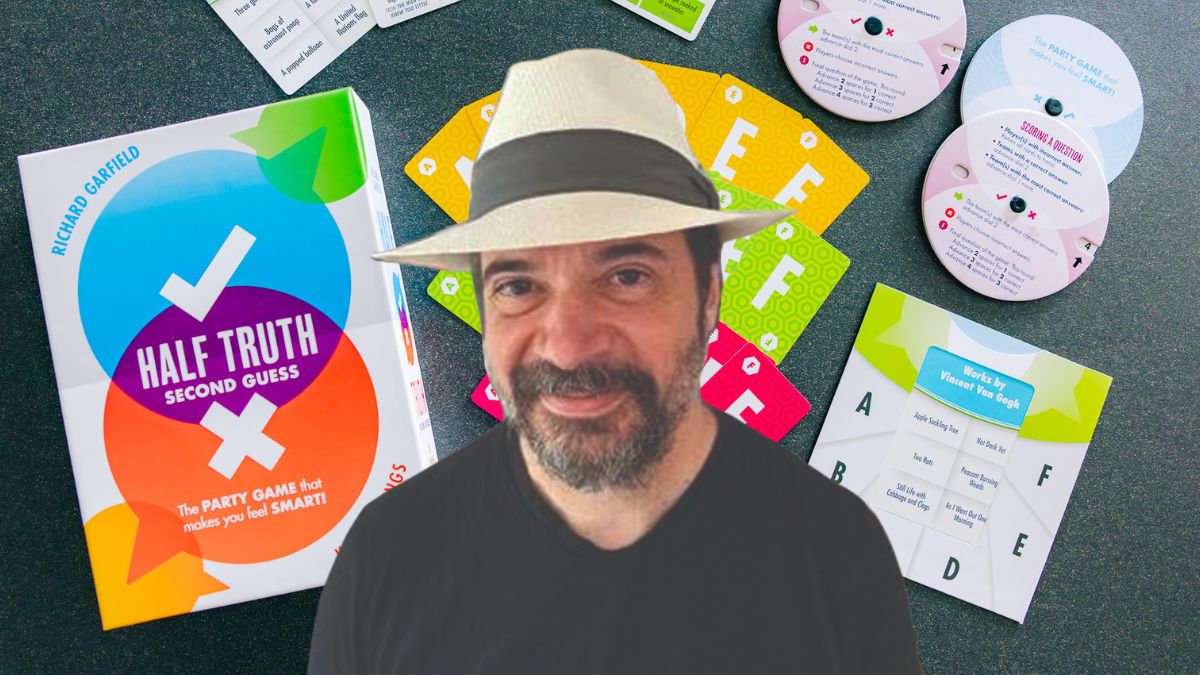

That student was Richard Garfield. He went home and started tinkering with an old idea he’d been kicking around for nearly a decade.

He called it Mana Clash. Today, we know it as Magic: The Gathering.

The Math Behind the Magic

Richard Garfield wasn't just some guy with a hobby. He was finishing a Ph.D. in combinatorial mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania. That matters. A lot. Most games back then were closed systems—you bought a box, and everyone played with the same components. Garfield’s "big brain" moment was applying combinatorics to a game that didn't have a fixed deck.

Basically, he wanted a game where the rules could be broken.

His biggest inspiration wasn't Dungeons & Dragons, though he loved it. It was a 1977 board game called Cosmic Encounter. In that game, every player gets a unique alien power that lets them cheat in a specific way. Garfield took that concept and miniaturized it. Instead of one alien power, every single card in your hand became a way to bend the rules.

You've got to realize how radical this was. In 1993, the idea of a "Trading Card Game" didn't exist. People collected baseball cards and played bridge, but nobody had thought to smash the two together.

Why the "Power Nine" Even Exist

There’s a common myth that Garfield made cards like Black Lotus and Ancestral Recall super powerful just to sell packs. Honestly? It was the opposite.

In the early playtests, Garfield assumed that no one would ever own more than a few dozen cards. He figured players would buy a couple of packs, trade with friends at the kitchen table, and that would be it. If a card was "Rare," he thought maybe one person in an entire town would have it.

He didn't account for the "whales." He didn't realize people would buy cases of product to find the strongest stuff.

Because he expected the card pool to be naturally diluted, he pushed the power level of rares to make them feel special. He once said that if the rare cards weren't interesting, the game would just be a "money game" where the rich kids win. He actually tried to put the most "raw power" in common cards—think Lightning Bolt or Dark Ritual—so that any kid with five bucks could compete.

The fact that the "Power Nine" became $50,000 collectibles is a complete accident of his original math.

The Shell Company and the "Gathering"

The launch of Magic: The Gathering was actually kind of a legal mess. Wizards of the Coast was being sued by Palladium Books over a different product at the time. To protect his invention, Garfield and Adkison formed a shell company called "Garfield Games."

Even the name was a backup.

They wanted to call it just Magic, but lawyers told them the word was too generic to trademark. They tried Mana Clash, but nobody liked it. Finally, they settled on Magic: The Gathering. The "Gathering" part was supposed to be a subtitle for the first set, with the plan to change it to something like Magic: Ice Age later. But the first name stuck so hard they couldn't get rid of it.

The Proposal Card

If you want to know the kind of person Richard Garfield is, you look at the "Proposal" card.

When he wanted to propose to his girlfriend, Lily Wu, he didn't just get down on one knee. He had a professional artist, Quinton Hoover, illustrate a one-of-a-kind Magic card. It was a sorcery that literally read: "Allows Richard to propose to Lily."

Here’s the kicker: Garfield insisted on playing a real game to get the card out. He didn't want to "cheat" his own game. He actually lost the first few games before he could finally draw and cast it. She said yes, by the way. Only nine copies of that card exist, and they are some of the most legendary pieces of cardboard in history.

What Most People Get Wrong About Balance

Nowadays, players complain if a card is 2% too strong. They want perfect balance.

Garfield’s philosophy was different. He liked the "swingy" nature of the game. He felt that if the better player won 100% of the time, the game would eventually become boring. He intentionally left room for luck and "broken" interactions because that’s what created stories.

He wanted you to walk away from a table saying, "You won't believe what happened," not "I executed a statistically superior 54% win-rate strategy."

✨ Don't miss: Why Bull Blitz Slot Machines Keep Winning Over the Casino Floor

Actionable Insights for Players and Designers

Looking at Garfield's work teaches us a few things that still apply to the game today:

- Rarity isn't just about price: In the original design, rarity was a tool to limit how often a specific "rule-breaking" effect appeared in a local meta. If you're building your own cube or deck, think about the "scarcity" of your effects.

- The "Golden Rule" of Games: If a card's text contradicts the rulebook, the card wins. This is the foundation of MTG’s longevity.

- Flavor drives mechanics: Garfield didn't start with "Blue/Green," he started with the feel of the colors. If you're struggling to understand a complex deck, look at the art and the flavor text. Usually, the "vibe" of the deck tells you how it wants to be played.

Richard Garfield eventually left Wizards of the Coast to design other things—Netrunner, Keyforge, even helping out on Artifact. But he always comes back to Magic every few years to help design a set like Dominaria (2018). He’s the "visiting professor" who occasionally reminds everyone that at its heart, this isn't a stock market.

It’s just a game where you get to be a wizard.

To truly understand the game, stop looking at price charts for a second. Go find a weird, "bad" rare card from an old set. Try to build a deck around it. That spirit of "discovery"—the idea that you might find something no one else has seen—is exactly what Richard Garfield was trying to capture in his basement three decades ago.