You’re standing on the sand at Lake Worth Beach, Florida. The sun is out. The water looks, honestly, pretty inviting. There’s a spot right between two sections of crashing waves where the water is calm and flat. It looks like the perfect place to take a dip without getting hammered by the surf.

But that "calm" spot is exactly where the danger hides.

Most people think of the ocean as a series of waves coming at them. They don't think about where all that water goes once it hits the shore. It has to go back out. A rip current is basically the ocean’s way of exhaling. It is a narrow, powerful channel of water moving away from the shore, often at speeds that would make an Olympic swimmer look like they’re standing still.

The Science of the "River in the Sea"

So, what is a rip current exactly? It’s not a "rip tide," and it’s definitely not "undertow." Those are terms people throw around a lot, but they’re technically wrong. A rip current is a horizontal flow of water. It doesn't pull you under; it pulls you out.

Imagine a bathtub. If you push all the water to one side with your hands, it’s eventually going to rush back to the other side to level itself out. On a beach, waves are constantly pushing water toward the land. This creates something scientists call "wave setup"—a slight increase in the water level at the shoreline.

This water wants to get back to the deep ocean. It seeks the path of least resistance. Usually, that’s a low spot in a sandbar or a gap near a jetty or pier. The water funnels through that gap like a river, creating a fast-moving current.

- Speed: Average rips move at 1–2 feet per second.

- Top Speed: They can pulse up to 8 feet per second.

- Range: Some end just past the breakers, while others can extend hundreds of yards into the open sea.

You've probably heard that they only happen during storms. Not true. You can have a perfectly sunny day with 3-foot waves and still get a "flash rip" that appears and disappears in minutes.

How to Spot a Rip Current Before You Step In

Honestly, spotting them is a bit of an art form. Even experts like Dr. Greg Dusek from NOAA suggest taking at least 10 minutes to watch the water from an elevated position—like a sand dune—before you even touch the water.

💡 You might also like: New Castle New Hampshire: What Most People Get Wrong

Look for the "dark gap." Since rip currents are often located in deeper channels between sandbars, the water there looks darker. While the rest of the beach has white, foamy waves breaking, the rip current area might look suspiciously calm. This is the "trap" that catches most waders. They see a spot with no waves and think it's the safest place to swim.

You should also look for:

- Churning water: A line of "dirty" or sandy water moving away from the beach.

- Foam trails: Seaweed or debris floating steadily offshore.

- Broken patterns: A gap in the incoming wave lines.

The Deadly "Human Chain" and Other Myths

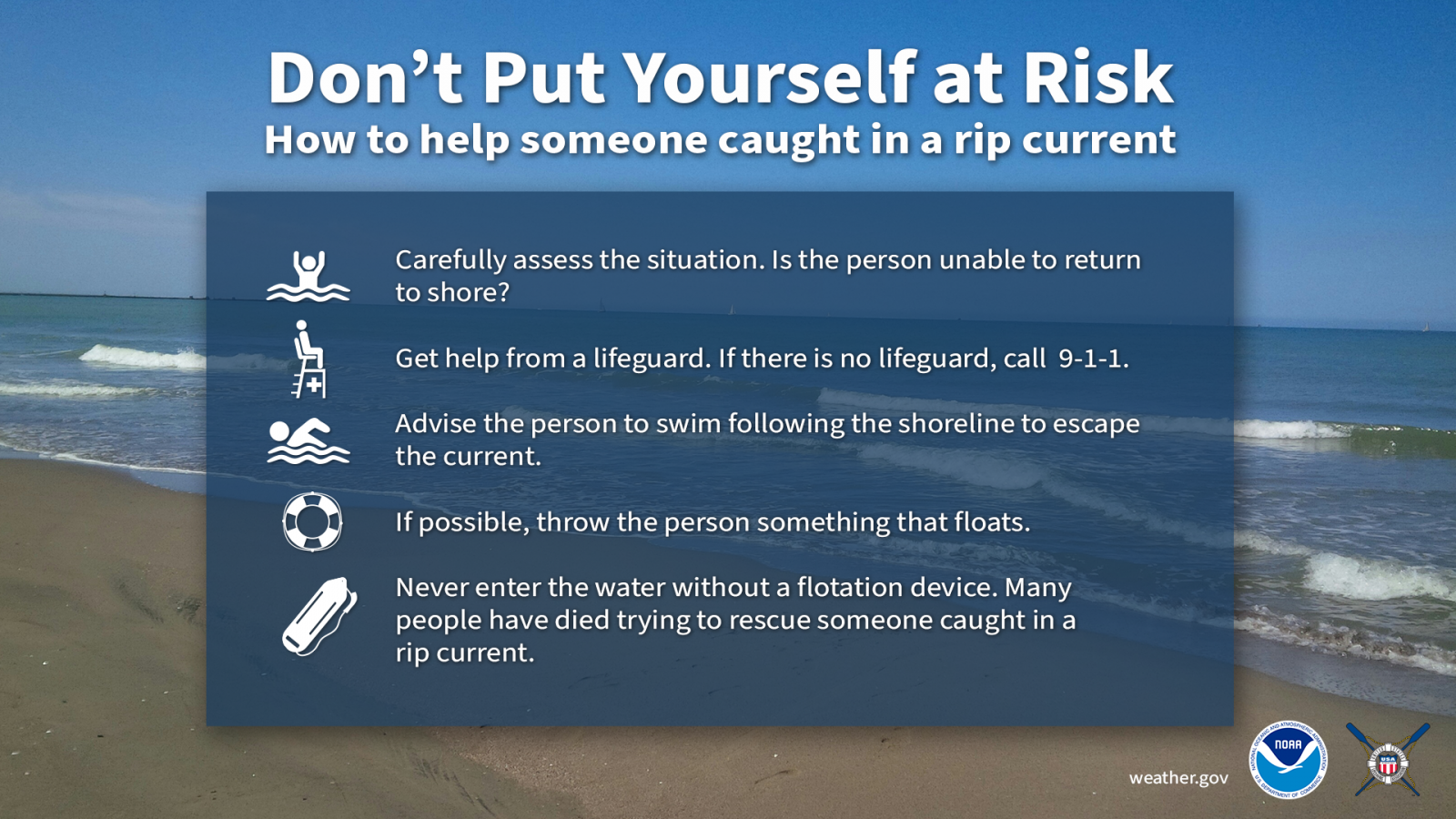

There is a terrifying misconception that if someone is caught in a rip, you should form a human chain to pull them back. Experts at the National Weather Service (NWS) actually warn against this.

Why? Because a rip current is strong enough to break that chain and pull everyone else in with them. Now, instead of one person in trouble, you have five or ten.

Another big myth is the "undertow." People fear being dragged to the bottom of the ocean floor. While a heavy wave might knock you down and make you feel like you’re being pulled under, a rip current is strictly a surface-to-mid-depth phenomenon. It wants to take you for a ride, not bury you.

👉 See also: Club Mac Resort Majorca: Why Families Keep Going Back (And What to Watch Out For)

Why Do People Actually Drown?

It isn't the water itself that kills; it's the panic. When a swimmer feels themselves being pulled away from their family on the shore, their first instinct is to swim as hard as they can straight back to the beach.

This is like trying to run up a down-escalator. You exhaust yourself in minutes. Once the muscles give out and the heart rate is through the roof, that’s when the situation becomes fatal. The United States Lifesaving Association (USLA) estimates that over 100 people die this way every year in the U.S. alone.

Survival: The "Break the Grip" Strategy

If you find yourself moving backward into the ocean, the very first thing you need to do is breathe. You aren't going to sink. The water is actually helping you stay afloat because it's so turbulent.

1. Don't Fight the Current

Stop trying to swim toward the beach. You won't win. Instead, treat the current like a treadmill you need to step off of.

👉 See also: San Diego Tallest Buildings: What the FAA Isn't Telling You

2. Swim Parallel

Since most rip currents are narrow—rarely more than 50 to 100 feet wide—you can usually escape by swimming sideways, parallel to the shoreline. Once you feel the "pull" stop and you see waves breaking around you again, you can start heading back to shore at an angle.

3. The "Float and Wave" Method

If you’re not a strong swimmer or you're already tired, just float. Many rip currents eventually curve back toward a sandbar or dissipate just beyond the surf zone. Keep your head above water, stay calm, and wave your arms to signal for help.

Actionable Safety Steps for Your Next Trip

Knowing what a rip current is is only half the battle. You have to change how you behave at the beach.

- Check the Forecast: The NWS provides a "Surf Zone Forecast." If it says "High Rip Current Risk," stay out of the water. Period.

- The Waist-Deep Rule: Most rescues happen when people are waist-deep and a "rip pulse" knocks them off their feet. If the waves are big, don't go deeper than your knees.

- Never Swim Near Structures: Jetties, piers, and groins are "rip magnets." Permanent currents often live right alongside these structures. Stay at least 100 feet away.

- The 1 in 18 Million Odds: Your chances of drowning at a beach with a lifeguard are 1 in 18 million. Those are pretty good odds. If you swim at an unguarded beach, you're taking your life into your own hands.

Before you jump in, find a lifeguard. Ask them, "Where are the rips today?" They'll usually be happy to point out the specific channels to avoid. A little bit of local knowledge is worth more than all the swimming lessons in the world.

To stay safe, always keep a flotation device nearby and never enter the water alone. If you see someone else in trouble, throw them something that floats and call 9-1-1 immediately rather than jumping in yourself.