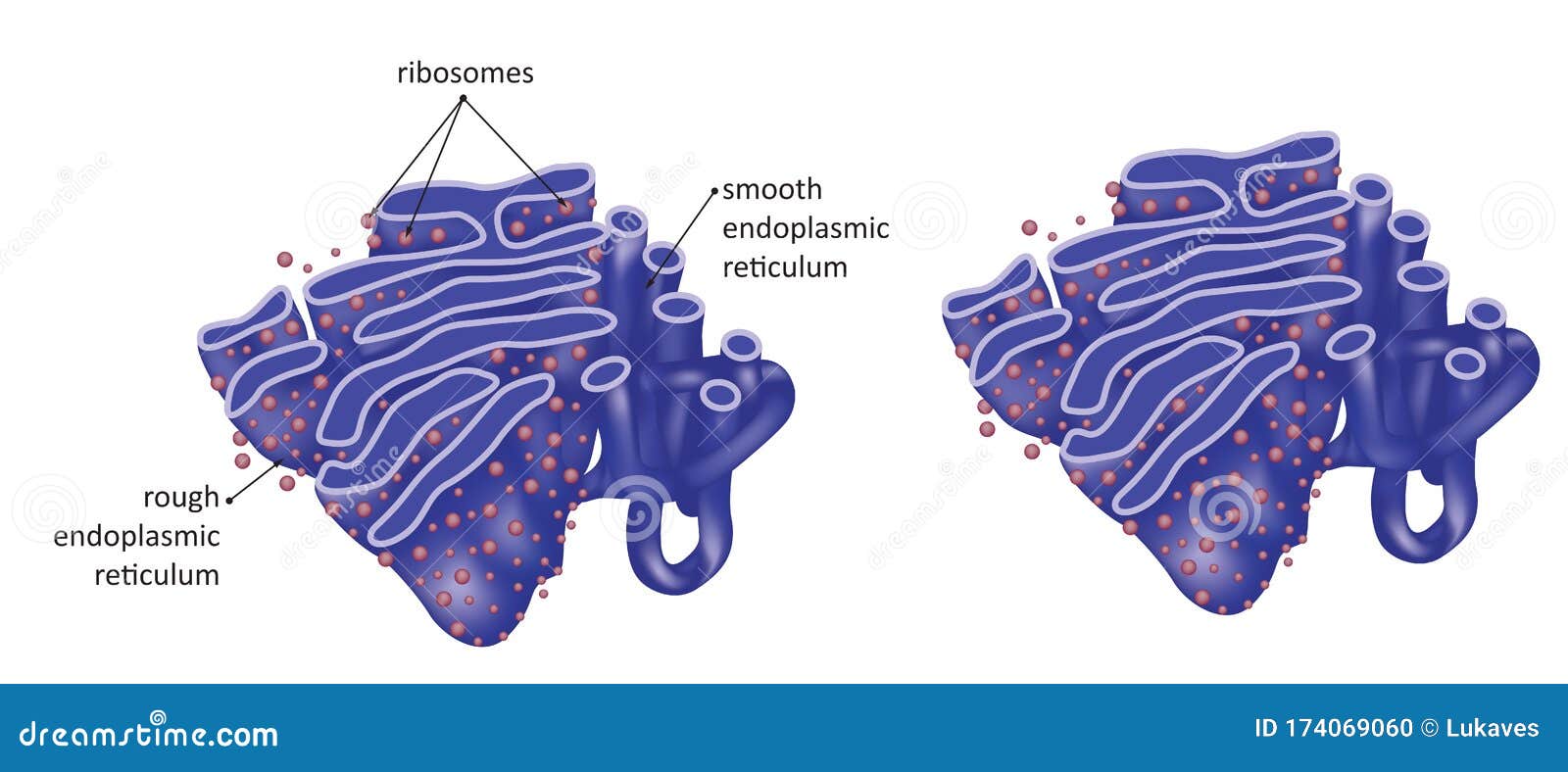

You’ve probably seen them in every biology textbook since the ninth grade. Those weird, blue or purple squiggly shapes huddled around the cell nucleus, looking somewhat like a stack of flattened pancakes or a maze gone wrong. But here’s the thing: most rough endoplasmic reticulum images we see are actually massive oversimplifications.

When you look at a stylized 3D render, it’s clean. In reality? It’s a chaotic, crowded, and incredibly high-speed manufacturing floor. If the cell were a city, the rough ER (RER) isn't just a factory; it's the specific factory that builds the machines that make the city run. It’s covered in ribosomes, which give it that "rough" appearance in electron micrographs, and those tiny dots are essentially the hard laborers of the biological world.

Why Real Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum Images Look Grainy

If you search for "real" photos rather than diagrams, you're going to see a lot of black-and-white, grainy textures. These are Transmission Electron Micrographs (TEM). We can't use regular light microscopes to see the RER because the structures are just too small. The wavelengths of visible light are literally too fat to resolve the fine details of the ER membrane.

Standard RER membranes are only about 5 to 8 nanometers thick. To put that in perspective, a human hair is about 80,000 to 100,000 nanometers wide. You need a beam of electrons to bounce off the specimen to get any kind of clarity. When you look at these rough endoplasmic reticulum images, the dark spots you see are the ribosomes. They aren't just sitting there for decoration. They are physically docked into the membrane via protein complexes called translocons.

Honestly, it’s a bit of a miracle we can see them at all. Scientists like George Palade, who actually won a Nobel Prize for this stuff back in the 70s, spent years perfecting the art of "fixing" cells in glutaraldehyde just so they wouldn't fall apart before the electron beam hit them.

The Secret Life of Cisternae

The flattened sacs you see in these images are called cisternae. They aren't just empty space. The interior, or the lumen, is a highly specialized environment. It’s packed with chaperones—proteins whose entire job is to make sure other proteins fold correctly.

Imagine a long piece of yarn being shoved into a room. If you just leave it there, it gets tangled. The RER lumen is the room, and the chaperones are the hands that knit that yarn into a specific sweater shape. If the sweater is shaped wrong, the RER has a "quality control" department that literally shreds the protein and recycles the parts. This is known as ER-associated degradation (ERAD). It’s brutal, but necessary.

👉 See also: Northwestern Tech Rock Spring GA: What Most People Get Wrong

Misconceptions in Modern RER Visuals

Most rough endoplasmic reticulum images suggest the organelle is static. Like it’s just sitting there.

It isn't.

It’s a shifting, undulating sea. Recent live-cell imaging using fluorescent tags (like GFP, the green fluorescent protein from jellyfish) shows that the ER tubules are constantly extending, retracting, and sliding along the cell's cytoskeleton. It’s more like a lava lamp than a brick building.

Another huge misconception? That the rough ER and smooth ER are totally separate "rooms." They aren't. They are different regions of the same continuous membrane system. One part just happens to have ribosomes "glued" to it, while the other—the smooth ER—is busy making lipids and detoxifying chemicals without the help of protein-makers.

What You See in High-Res 3D Reconstructions

Lately, we’ve moved past flat 2D slides. Technologies like Cryo-Electron Tomography (Cryo-ET) allow researchers to freeze a cell instantly and take "slices" of it while it's in a near-native state.

When you look at these modern rough endoplasmic reticulum images, you notice something cool: the "pancake" stacks are connected by helical ramps. Think of a multi-story parking garage. The ribosomes need to move around, and the proteins inside need to travel. These ramps, often called Terasaki ramps, optimize the space so the cell can cram as much protein-making machinery as possible into a tiny volume.

The Health Connection: When the Images Change

You can actually tell how sick or stressed a cell is just by looking at the RER. In a healthy cell, the cisternae are neatly packed. But in a cell under "ER Stress"—maybe due to a viral infection or a neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer's—the RER starts to swell.

It gets bloated.

The ribosomes might even start falling off. This is a visual cue of the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR). If the cell can't fix the protein folding bottleneck, it triggers a self-destruct sequence (apoptosis). This is why researchers at places like the Salk Institute spend thousands of hours staring at rough endoplasmic reticulum images of brain cells. They’re looking for those subtle signs of swelling that signal the start of a disease long before a patient shows symptoms.

The Role of Specialized Cells

If you look at an image of a plasma cell (a type of white blood cell that pumps out antibodies), the RER takes up almost the entire frame. It’s huge. Why? Because antibodies are proteins. A single plasma cell can secrete thousands of antibodies per second.

💡 You might also like: Trump 2020 TikTok Ban: What Really Happened and Why It Still Matters

On the flip side, if you look at a skin cell, the RER is much more modest. It only makes what it needs for basic maintenance. This "form follows function" rule is the gold standard in cell biology. You can literally guess what a cell does for a living just by measuring the surface area of the rough ER in a micrograph.

How to Analyze RER Micrographs Like a Pro

If you’re a student or just a curious nerd looking at these images, don't just look at the "squiggles." Look for the junctions.

- Check the Density: High ribosome density usually means the cell is in a growth phase or secreting a lot of material.

- Look at the Nucleus: The outer membrane of the nuclear envelope is actually continuous with the RER. They are basically the same skin.

- Scan for Vesicles: Look for tiny bubbles breaking off the edges. Those are transport vesicles headed for the Golgi apparatus. It's the "outbox" of the factory.

The Future of Imaging

We are getting to a point where we don't just see the "rough" parts; we see the individual atoms. X-ray crystallography and advanced AI modeling (like AlphaFold) are being integrated with rough endoplasmic reticulum images to show us exactly how a ribosome sits on the membrane.

We’re moving away from "it looks like dots" to "we can see the specific amino acid chain being threaded through the membrane." It’s a wild time for microscopy.

Actionable Insights for Researchers and Students

If you are looking for high-quality, scientifically accurate images for a project or study, avoid general stock photo sites. They often get the proportions wrong or show "floating" ribosomes that aren't actually attached to anything.

Instead, head to the Cell Image Library or the Protein Data Bank (PDB). These repositories host actual raw data from peer-reviewed studies. When you use a real TEM image, you’re looking at the actual architecture of life, not just a graphic designer's best guess.

Next time you see those grainy black lines, remember you're looking at the very spot where your body's insulin is made, where your collagen is formed, and where the antibodies fighting off your last cold were "born." It’s messy, it’s crowded, and it’s perfectly engineered.

To get the most out of your search, always look for "TEM" or "SEM" prefixes in the image descriptions to ensure you're viewing actual biological structures rather than artistic interpretations. If you're a student, try sketching a 2D micrograph yourself; it's the fastest way to understand the spatial relationship between the nuclear envelope and the cisternae. For those in the medical field, pay close attention to the lumen width—variations there are often the first morphological signs of cellular pathology in liver and pancreatic biopsies.