Ever wonder why a single dead bulb on a string of old Christmas lights kills the whole vibe, while one burnt-out light in your kitchen doesn't plunge your entire house into darkness? It’s basically the most practical way to see the series circuit and parallel circuit difference in the real world. Most textbooks make this sound like some abstract math problem involving Greek letters and rigid diagrams. Honestly, it’s much simpler than that. It’s about how electricity flows—either like a single-lane dirt road or a massive multi-lane highway.

If you’re trying to wire a DIY solar project or just trying to pass an intro physics exam, you’ve gotta understand that these two setups behave in totally opposite ways. One is fragile but simple. The other is robust but eats up more wire and planning.

💡 You might also like: Strip mining of coal: What most people get wrong about how we move mountains

The Single-Path Logic of Series Circuits

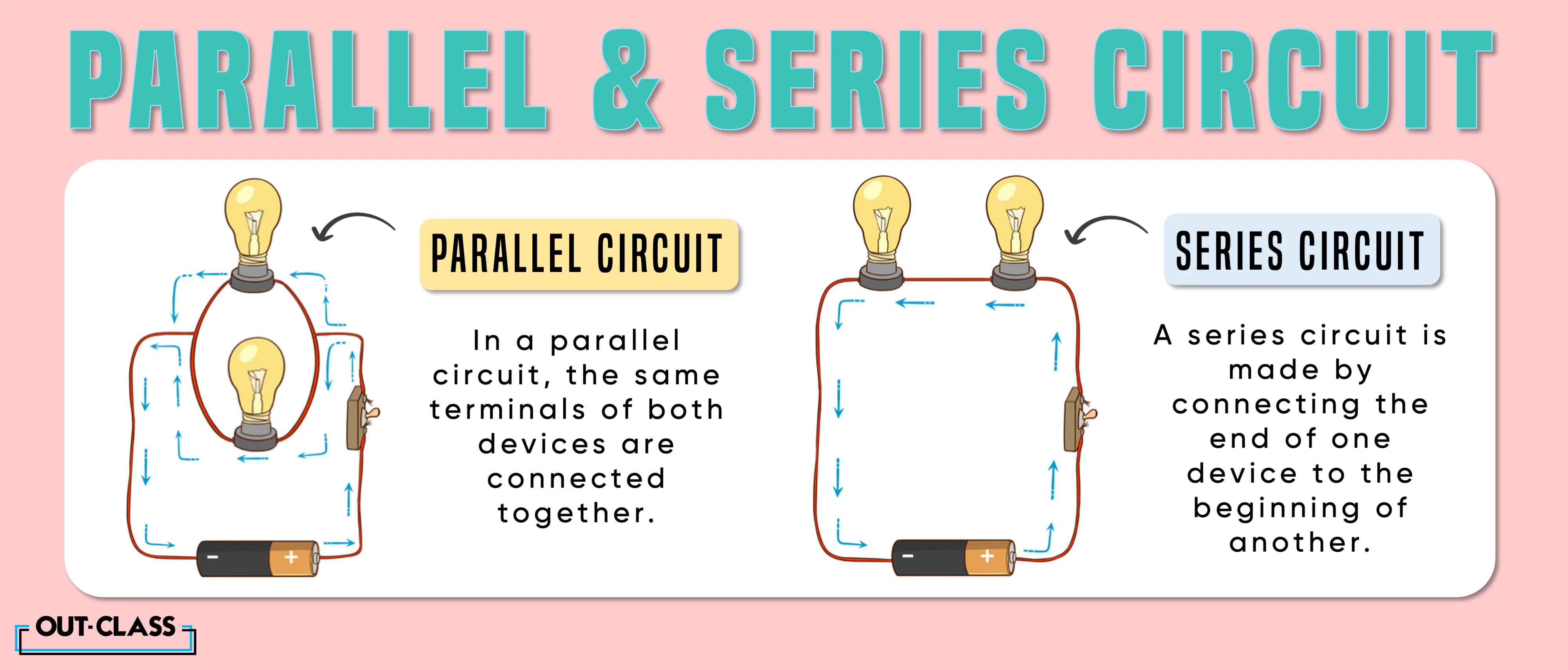

Think of a series circuit as a line at a crowded coffee shop. There is only one way forward. Every electron has to pass through every single component—every resistor, every bulb, every switch—in one continuous loop. If you break that loop anywhere, the party is over. The flow stops. This is why if you have a cheap string of lights and one bulb pops, the whole strand goes dark. The "bridge" is out.

In a series circuit, the current ($I$) is the same everywhere. Whether you measure it at the start, the middle, or the end, it’s identical. But the voltage ($V$) is a different story. The total voltage provided by your battery or power source gets "split" across every device. If you’ve got a 12V battery and three identical bulbs, each one only gets 4V. They’ll be dim. Really dim.

As you add more bulbs, the total resistance ($R_{total}$) just keeps climbing. You just add them up:

$$R_{total} = R_1 + R_2 + R_3...$$

It’s heavy lifting for the battery. This is why you rarely see house wiring done this way. Imagine if you had to turn on every single appliance in your house just to get the toaster to work. It’d be a nightmare.

Why Parallel Circuits Run the Modern World

Parallel circuits are the "choose your own adventure" version of electronics. Instead of one path, the current reaches a junction and splits. It can go through Branch A, Branch B, or Branch C. Because of this, every single branch is connected directly to the voltage source.

This is the big one: in a parallel circuit, the voltage is the same across all components. If you’re plugged into a 120V wall outlet, every single thing you plug in—your laptop, your lamp, your fridge—sees that full 120V. They don't have to share. This is why your lights don't get dimmer when you turn on the vacuum cleaner (unless you're overloading a breaker, but that's a different story).

Here is the weird part that trips people up. When you add more paths (resistors) in parallel, the total resistance actually goes down. It sounds counterintuitive, right? Think of it like a grocery store. If only one checkout lane is open, there’s a lot of "resistance" to people leaving. If the manager opens five more lanes, even if those lanes are narrow, the total resistance to the flow of people drops significantly.

The math looks a bit nastier, using reciprocals:

$$\frac{1}{R_{total}} = \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2} + \frac{1}{R_3}...$$

But basically, it just means that adding more stuff makes it easier for the total current to flow from the battery.

The Trade-offs: Reliability vs. Simplicity

Nothing is free.

Series circuits are cheap. They use less wire. They are great for simple things like a flashlight or a basic toy. But they are incredibly unreliable for complex systems. If one component fails, the entire system fails. It’s a "single point of failure" design.

Parallel circuits are the gold standard for reliability. If a bulb burns out in your bedroom, the TV in the living room keeps humming along. The paths are independent. However, they require way more wiring and can be more dangerous if not managed correctly. Since adding more branches lowers resistance, the total current can spike to dangerous levels. That’s why your home has a breaker box. If you pull too much current by plugging in three space heaters on one parallel circuit, the breaker trips to prevent the wires from literally melting and starting a fire.

Real-World Examples You See Every Day

Look at your phone. Inside, it's a massive, microscopic maze of parallel circuits. Different chips (the CPU, the screen, the radio) need different amounts of power, but they all need to function independently. If your camera module dies, you still want to be able to make a phone call.

Batteries are a fun example of the series circuit and parallel circuit difference.

✨ Don't miss: Motorola Cell Phone 2000 Models: What Most People Get Wrong About the Y2K Era

- Batteries in Series: If you put two 1.5V AA batteries end-to-end, you get 3V. You’re boosting the "pressure" (voltage), but the capacity (how long they last) stays the same.

- Batteries in Parallel: If you wire them side-by-side, you still only have 1.5V, but they will last twice as long. You've increased the total amp-hours.

Electric vehicles like Teslas actually use a mix of both. They wire thousands of small lithium-ion cells in "strings" (series) to get the high voltage needed to turn the motor, and then wire those strings in parallel to give the car enough range to actually get you to work.

Maintenance and Troubleshooting

If you're staring at a piece of broken gear, knowing the circuit type tells you exactly how to fix it.

- Check for "The Break": In a series circuit, you're looking for the one broken link. Use a multimeter to check continuity across each component. The one that shows "Open" is your culprit.

- Check for "The Short": In parallel, troubleshooting is usually about finding which branch is drawing too much power or which one has a short to ground.

- Voltage Drops: If your lights are dimming, you likely have too much resistance in a series connection or you're overtaxing a parallel branch.

Essential Summary of the Differences

Don't let the technical jargon confuse you. Here is the "too long; didn't read" breakdown of how these things actually behave when you're working with them.

In a Series Setup, the current is a constant. It’s a single stream. The voltage, however, is shared. It gets weaker as it passes through more stuff. If you add more resistors, the total resistance goes up and the current drops. One break kills everything. Simple as that.

In a Parallel Setup, the voltage is the constant. Every component gets the full "push" of the power source. The current is what gets shared or split between the branches. Adding more branches actually makes it easier for electricity to flow, meaning total resistance goes down. If one branch breaks, the others don't care. They keep working.

✨ Don't miss: Radu Oncescu: What Most People Get Wrong About This Social Media Expert

Taking Action: Your Next Steps

If you’re planning to build something or just trying to understand your home’s electrical system, start by mapping it out.

- Audit your DIY projects: If you’re building a solar array or a battery pack, decide if you need more voltage (Series) or more capacity (Parallel). Most off-grid systems use a combination called "Series-Parallel" to hit a specific voltage target like 24V or 48V while maximizing runtime.

- Check your Christmas lights: If you have a dead strand, look at the bulbs. Modern ones often have a "shunt" inside that tries to keep the circuit closed even if the filament breaks, turning a series-style failure into a functional circuit. If the whole strand is out, check the tiny fuse in the plug.

- Multimeter Practice: Get a cheap digital multimeter. Set it to the Ohms ($\Omega$) setting and measure the resistance of two resistors separately. Then, twist them together in series and measure again. Then, hold them together in parallel and watch the resistance drop below the value of the smallest resistor. Seeing it happen on a screen makes it click way faster than reading a book ever will.

Understanding these fundamentals is the difference between being a frustrated "parts changer" and someone who actually understands how the world is wired.