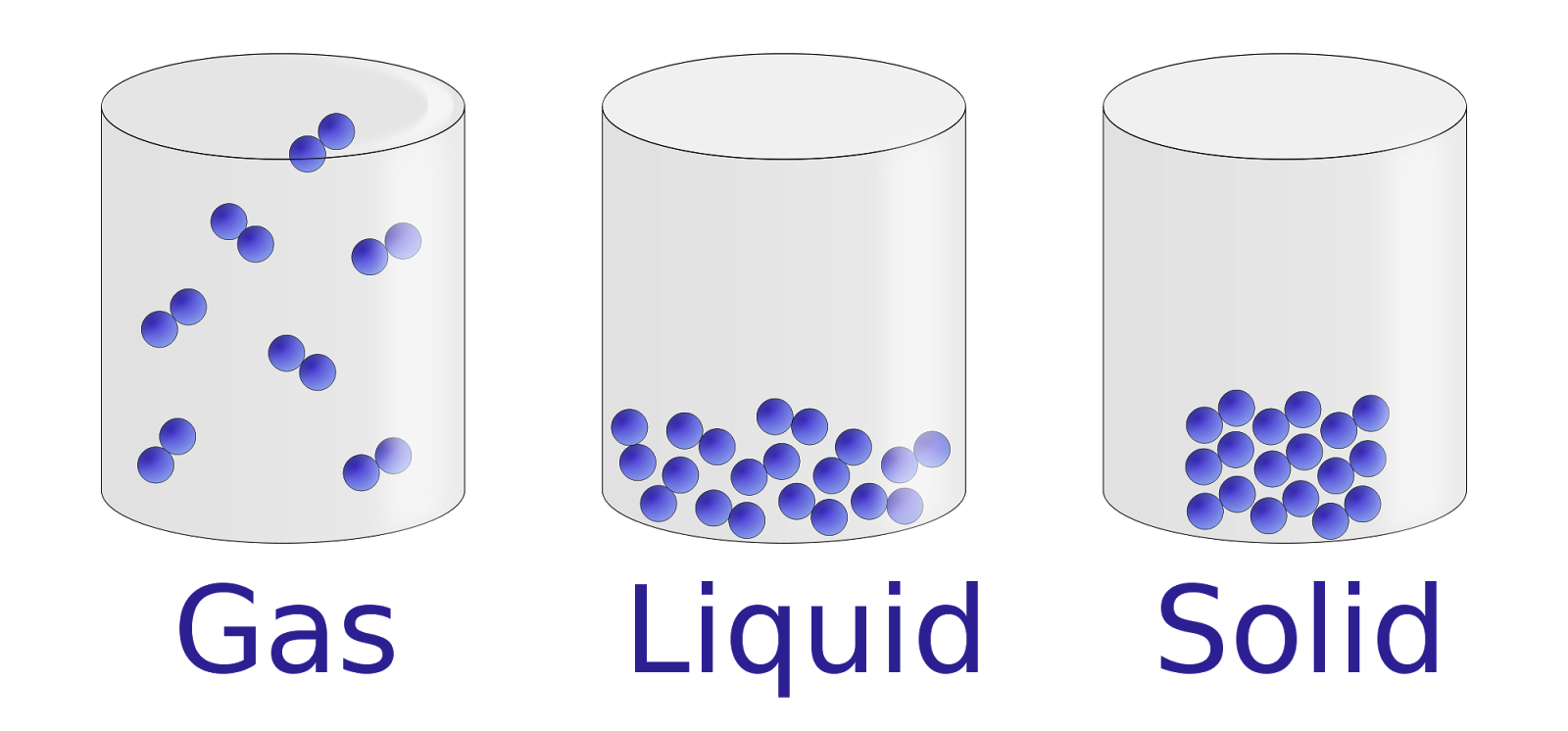

You’ve seen them a thousand times. Every science textbook from third grade through high school features those classic solid liquid gas pics that look like marbles in a box. In the solid frame, the marbles are perfectly stacked in a grid. In the liquid one, they’re slightly messy at the bottom. For the gas, they’re just flying around with little "whoosh" lines behind them. It's simple. It's clean.

It’s also kinda lying to you.

When we look at visualizations of matter, we’re usually looking at a massive oversimplification that ignores how molecules actually behave in the real world. If you’re searching for solid liquid gas pics to understand the universe or just to help a kid with their homework, you need to know what those dots actually represent—and where the drawings fail. Matter isn't just about "closeness." It’s about energy, chaos, and the weird dance of intermolecular forces.

The Problem with Your Standard Solid Liquid Gas Pics

Most images suggest that the only difference between a block of ice and a glass of water is how close the molecules are. That’s a huge misconception. Take water, for example. Ice is actually less dense than liquid water. That’s why it floats. If you looked at an accurate pic of ice versus water, the solid version would actually show the molecules spreading out into a hexagonal lattice, leaving more empty space than the liquid.

👉 See also: Google for iPhone App: Why You Should Probably Stop Using Safari

Most generic diagrams don't show that. They just show the solid as "tighter."

Why the "Marble" Analogy Fails

Molecules aren't hard little balls. They’re fuzzy clouds of probability. When you see a diagram of a gas, the "pics" often show the particles taking up maybe 10% of the container's volume. In reality? At room temperature and standard pressure, the actual molecules in a gas take up about 0.1% of the space. The rest is just... nothing. Total emptiness. If a diagram were drawn to scale, you wouldn't even see the gas particles. They'd be microscopic specks lost in a giant void.

Solids: Not as Still as They Look

Look at any solid liquid gas pics representing a solid. It looks dead. Static. Frozen.

But if you could actually see the atoms in a "solid" piece of iron or a diamond, they’d be vibrating like they just drank ten cups of coffee. They are constantly jiggling. They’re locked in place by chemical bonds, sure, but they have kinetic energy. As you heat a solid up, those vibrations get more violent. Eventually, they vibrate so hard they break free from their fixed positions. That's melting.

Crystalline vs. Amorphous

Not all solids are created equal. Most "pics" show a perfect crystal lattice—think salt or quartz. These are crystalline solids. But what about glass? Or plastic? Or wax? These are amorphous solids. Their internal structure is a mess. They look like a liquid that just stopped moving suddenly. If you’re looking for high-quality educational visuals, you need to find images that distinguish between these two, or you're missing half the story of how materials actually work.

The Chaos of the Liquid State

Liquids are the hardest state to draw accurately. In solid liquid gas pics, liquids are usually shown as a disorganized pile of dots at the bottom of a beaker.

Actually, liquids have what scientists call "short-range order." For a split second, a group of molecules might look like a solid, then they slide away. It’s a constant state of breaking and forming bonds. This is why liquids can flow but can’t be compressed much. They’re already touching, unlike the gas particles, but they don't have the long-range discipline of a solid.

Gas: The Great Loners of the Universe

When you look at solid liquid gas pics for gases, focus on the "mean free path." That’s a fancy way of saying the average distance a particle travels before it slams into something else.

🔗 Read more: How to Save a Video From Facebook to Camera Roll Without Losing Your Mind

In a typical gas at sea level, a molecule travels about 1,000 times its own diameter before hitting another molecule. Imagine a person running 2,000 meters before bumping into another human. That’s the scale we’re talking about. Most diagrams make gas look crowded. It’s not. It’s lonely.

What Most Pics Forget: The "Fourth" and "Fifth" States

If you're looking for a complete set of solid liquid gas pics, you’re probably missing Plasma. It’s the most common state of matter in the universe (think stars and lightning), but it gets left out of the "Big Three" because it doesn't happen naturally on Earth very often.

Plasma is basically a gas that got so hot its electrons got ripped off. Now you have a soup of positive ions and free electrons. It conducts electricity. It responds to magnets. It’s wild.

Then there’s the Bose-Einstein Condensate (BEC). This only happens near absolute zero. In BEC diagrams, the particles don't even act like individuals anymore. They overlap and behave like one single "super-atom." It’s quantum mechanics visible to the naked eye. If your collection of matter pics doesn't include these, you're only seeing the Earth-centric version of reality.

How to Spot a High-Quality Scientific Illustration

If you are a teacher, a student, or just a nerd like me, don't settle for the first image on Google Images. Here is how to vet solid liquid gas pics for actual accuracy:

- Check the Water Exception: Does the ice diagram show more space between molecules than the liquid? If yes, the creator knows their stuff.

- Look for Motion Blurs: Good diagrams use shading or "tails" to show that particles are moving. A solid should have tiny vibration markers; a gas should have long vectors.

- Check Volume Ratios: A gas container should look mostly empty. If it looks like a ball pit, it’s a bad representation.

- Temperature Context: Does the image indicate that energy is the driving force? Heat is just motion. The "gas" pics should look "hotter" (faster) than the "solid" pics.

Real-World Applications of These Visuals

Why does this matter? Because understanding how these particles look and move helps us solve real problems.

Engineers at NASA look at gas particle simulations to understand how spacecraft heat up during reentry. Pharmaceutical researchers look at "pics" of solid crystal structures to figure out how a pill will dissolve in your stomach. If they used the oversimplified versions from a 4th-grade textbook, the rocket would burn up and the medicine wouldn't work.

The transition between these states—the "phase change"—is where the real magic happens. When you see a pic of "sublimation" (dry ice turning straight to gas), it shows the molecules skipping the liquid dance entirely. They go from shivering in a crowd to sprinting into the void.

Practical Next Steps for Visual Learners

Stop looking at 2D circles. If you really want to grasp how solids, liquids, and gases work, you need to see them in motion.

- Search for "Molecular Dynamics Simulations": Instead of static solid liquid gas pics, look for videos. These use supercomputers to calculate the actual paths of atoms.

- Use PhET Interactive Simulations: The University of Colorado Boulder has a "States of Matter" sim that lets you heat and cool different molecules (Neon, Argon, Oxygen, Water) in real-time. You can see the "water exception" for yourself.

- Compare Polar vs. Non-polar: Look for pics that show why the particles stick together. Some molecules have a "plus" and "minus" side (like water), which makes their liquid and solid states much more organized than something like Methane.

The world isn't made of marbles. It's made of vibrating, charging, colliding energy. The next time you see a chart of the three states of matter, remember that the empty space between the dots is just as important as the dots themselves.

Actionable Insight: When teaching or learning the states of matter, always verify the substance being depicted. If the diagram uses "generic" particles to represent water, it is fundamentally inaccurate regarding density. Always seek out "molecularly accurate" visualizations for a true understanding of phase transitions.