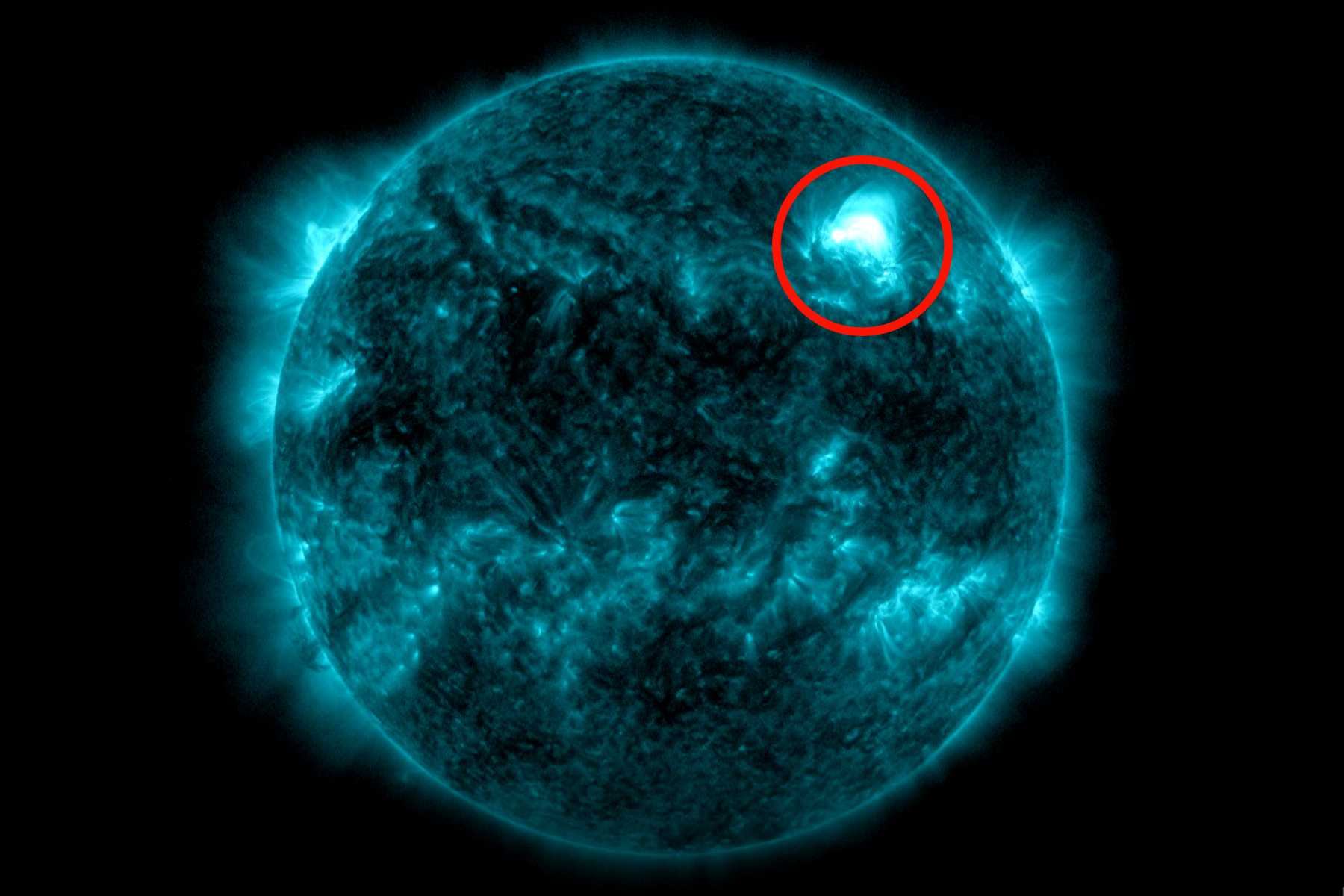

The sun isn't just a glowing ball of light that gives you a tan or makes the crops grow. It’s a violent, magnetic beast. Right now, as you read this, the sun is crackling with energy, shedding its outer atmosphere into the void. Sometimes, it throws a literal temper tantrum. We call those space weather solar flares.

They happen fast.

📖 Related: Schneider Electric Data Center News: Why AI Is Forcing a Total Redesign

Basically, magnetic field lines near sunspots get so tangled they eventually snap and reconnect. Think of it like a rubber band stretched until it breaks, but instead of just hitting your finger, it releases the energy of millions of hydrogen bombs all at once. Light and X-rays hit Earth in eight minutes. You don't get a warning. If you’re a satellite operator or a high-frequency radio user, your day just got a lot more complicated.

Honestly, most people think "space weather" is just about the Northern Lights. Sure, the aurora borealis is gorgeous, but it’s actually the visible symptom of a planet-wide magnetic shielding struggle. When a massive solar flare hits, it’s not just a light show. It’s a direct threat to the silicon-based world we’ve built.

What actually happens during space weather solar flares?

Most folks get the terminology mixed up. You’ve got your solar flares, which are flashes of light and radiation. Then you’ve got Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs), which are actual clouds of plasma—billions of tons of solar material—hurling through space. They often happen together, but they aren't the same thing.

When a flare erupts, it sends X-rays and extreme ultraviolet radiation screaming toward Earth at the speed of light. This hits our ionosphere—the part of the atmosphere that reflects radio waves—and basically "puffs" it up. Suddenly, the GPS signals you rely on to find a Starbucks have to travel through a much denser medium. This causes timing errors. A few meters of error might not matter to you, but for an autonomous cargo ship or a military drone? It's a huge deal.

Dr. Holly Gilbert, a former director of the High Altitude Observatory, has often pointed out that the sun is currently ramping up. We are in Solar Cycle 25. This means we are heading toward a "solar maximum," a period where the sun is exceptionally active. During these peaks, space weather solar flares aren't just rare anomalies; they become a weekly or even daily occurrence.

It's kinda scary how much we rely on a stable sun.

The Carrington Event: A cautionary tale from 1859

If you want to understand the stakes, look at 1859. British astronomer Richard Carrington saw a "white-light flare" with his own eyes. Within hours, telegraph systems around the world went haywire. Some operators reported that they could send messages even after they disconnected the batteries—the atmosphere itself was so charged it was powering the wires.

Papers were caught on fire. Sparks flew from the equipment.

If a Carrington-class event hit today? Some estimates from Lloyd’s of London suggest the economic damage to the U.S. alone could exceed $2 trillion. We aren't just talking about your phone dying. We’re talking about high-voltage transformers blowing out, leaving cities in the dark for months because these things aren't exactly sitting on a shelf at Home Depot. They take years to manufacture and install.

Why your GPS is the first thing to go

GPS satellites live in Medium Earth Orbit (MEO). They are basically extremely precise clocks in the sky. To tell you where you are, your phone calculates the time it takes for a signal to arrive from at least four different satellites.

- The flare hits the ionosphere.

- The ionosphere becomes "turbulent."

- The signal gets delayed or "scintillates" (wiggles).

- Your position jumps 50 feet to the left while you're driving 70 mph.

It's not just about getting lost. Aviation relies on GPS for landing in low visibility. Precision agriculture uses it to plant crops within inches of accuracy. When space weather solar flares mess with that signal, the "smooth" operation of modern society starts to grind.

The grid is the real victim

The biggest worry for experts like those at NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) isn't your cell phone signal—it's the power grid. When a flare is followed by a CME, it can trigger a geomagnetic storm. These storms induce currents in long-distance power lines.

Think of the power grid as a giant antenna. It’s literally built to pick up energy. When the Earth's magnetic field starts shaking because of a solar hit, it creates "Geomagnetically Induced Currents" (GICs). These currents flow into transformers that aren't designed to handle them. The cores saturate, the oil boils, and the whole thing can melt down.

In 1989, a relatively modest solar storm knocked out the entire Hydro-Québec power grid in about 90 seconds. Six million people were in the dark for nine hours. And that was with 1980s technology. Our current grid is much more interconnected, meaning a failure in one spot can cascade across state lines much faster.

Does the atmosphere protect us?

Mostly, yeah. We’re lucky. Earth has a molten iron core that generates a massive magnetic shield called the magnetosphere. It deflects the vast majority of the "solar wind." Without it, we’d be a barren rock like Mars.

But even a shield has holes. Near the poles, the magnetic field lines funnel toward the surface. That’s why the auroras happen there. It’s also why trans-polar flights—like the ones from New York to Hong Kong—are the most at risk during space weather solar flares. Pilots often have to reroute to lower latitudes to avoid radiation exposure for the crew and to ensure they don't lose radio contact.

Radio blackouts are categorized by NOAA on a scale from R1 to R5.

- R1 (Minor): Slight degradation of HF radio.

- R3 (Strong): Wideout of HF radio on the sunlit side of Earth for an hour or so.

- R5 (Extreme): No HF radio contact for several hours. This is the "big one."

What are we doing about it?

We aren't just sitting ducks. We have "eyes" on the sun. The Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) and the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) sit a million miles away at a point called L1. They act like a buoy in the ocean, giving us about a 15 to 30-minute warning before the actual plasma cloud hits Earth.

It’s not much time, but it’s enough for power companies to "shed load" or for NASA to tell astronauts on the ISS to move to more shielded modules.

There's also the Parker Solar Probe, which is literally "touching" the sun's corona. It’s flying closer than any spacecraft in history, trying to figure out why the sun's outer atmosphere is millions of degrees hotter than its surface. Solving that mystery is the key to better predicting space weather solar flares before they even happen.

Actionable steps for the tech-conscious

While you can't stop a solar flare, you can certainly be prepared for the secondary effects. We live in an era of "just-in-time" supply chains, and space weather is one of those low-probability, high-impact events that can break those chains instantly.

- Offline Navigation: If you do a lot of hiking or off-roading, don't rely solely on live GPS. Download offline maps (like on Google Maps or Gaia GPS) or keep a physical map. During a flare, your GPS might be off by significant margins.

- Backup Power: If a major geomagnetic storm is predicted (G4 or G5 on the NOAA scale), ensure your devices are charged. While a flare won't "fry" your phone like an EMP might, a grid failure could leave you without power for days.

- Monitor the Data: You don't have to be a scientist to track this. Sites like SpaceWeather.com or apps like "Space Weather Reporter" give you real-time alerts. If you see an "X-class" flare has occurred, expect radio or GPS glitches within minutes.

- Understand the Scale: Don't panic over every "M-class" flare. These are common and usually only affect specialized equipment. It's the "X-class" events directed toward Earth that warrant your attention.

- Protect Sensitive Electronics: While a flare itself won't kill your laptop, the power surges it causes in the grid might. Using high-quality surge protectors is just common sense in a world where the sun is getting more active.

Space weather solar flares are a reminder that we live in a cosmic neighborhood. We’ve spent the last century building a world that is incredibly efficient but also incredibly sensitive to the moods of our star. Being aware of the "weather" above our atmosphere is just as important as checking the rain forecast on the ground.

📖 Related: What Does Melting Mean? The Science of Why Solids Just Give Up

Keep an eye on the K-index. It’s the metric used to characterize the magnitude of geomagnetic storms. If it hits an 8 or a 9, you might want to postpone that precision-drone flight or that long-distance radio marathon. The sun is waking up, and it’s better to be prepared than surprised.