Six miles off the coast of Crescent City, California, a jagged pillar of concrete and granite rises out of the grey Pacific. It looks lonely. Honestly, it looks like something out of a gothic horror novel. This is the St. George Reef Lighthouse, and for decades, it was basically considered the most dreaded assignment in the entire U.S. Lighthouse Service.

If you were a lightkeeper back in the day, getting sent here was a test of your sanity. The waves don't just hit the rock; they explode against it. We’re talking about swells that reached the lantern room 146 feet above the water. Imagine sitting in your kitchen, over a hundred feet in the air, and seeing a wall of seawater slam into your window. That wasn't a rare event. It was just Tuesday.

The history of this place is soaked in tragedy and some of the most impressive engineering of the 19th century. People often confuse it with easier-to-reach coastal lights, but St. George Reef is a different beast entirely. It sits on Northwest Seal Rock, a tiny speck in a graveyard of ships.

✨ Don't miss: Airfare From Harrisburg to Las Vegas: What Most People Get Wrong

The Disaster That Forced the Hand of Congress

You can’t talk about the St. George Reef Lighthouse without talking about the Brother Jonathan. In July 1865, this paddle-wheel steamer hit an uncharted rock in the vicinity during a massive storm. It went down fast. Out of 244 people on board, only 19 survived.

It was a nightmare.

The wreck was so devastating that the public demanded something be done. But the government dragged its feet. Why? Because building on a wave-swept rock six miles out at sea was considered nearly impossible. It took another wreck—the City of Chester—and years of lobbying before the project finally got the green light.

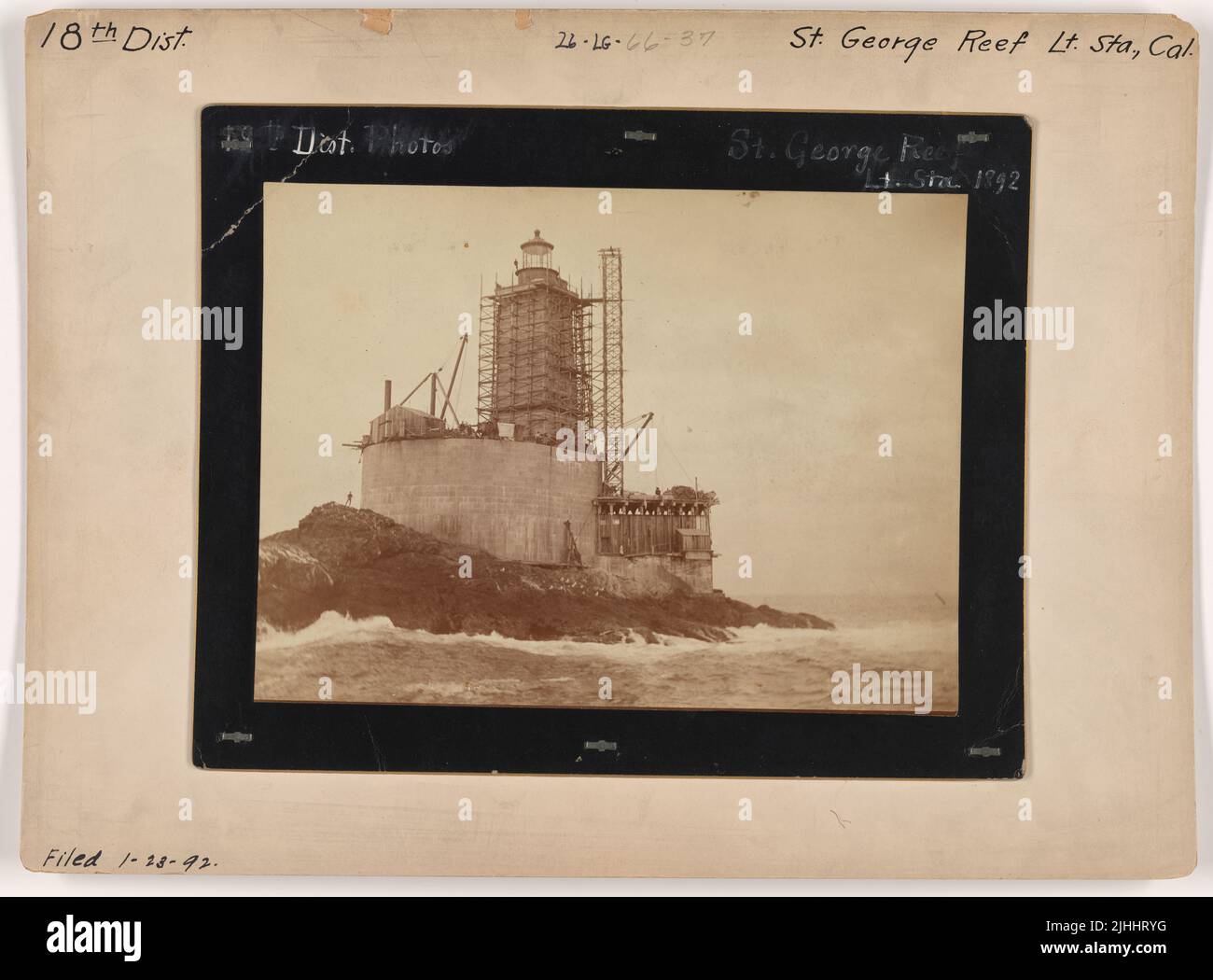

When they started construction in 1882, the engineers realized they weren't just building a tower; they were building a fortress. They had to quarry massive granite blocks from the Mad River, shape them precisely, and then ferry them out to a rock that was barely above water at high tide. It took ten years. Ten years of men living on a temporary working pier, constantly at risk of being swept away by "sneaker waves."

Life on the Rock: It Wasn't Just Lonely

Most people think being a lighthouse keeper was about peace and quiet. Maybe a little reading by the fire. At St. George Reef Lighthouse, it was more like being a prisoner in a very damp, very loud stone cell.

The keepers lived in the caisson—the massive square base of the tower. The walls were thick, but they couldn't drown out the vibration of the ocean. When the big storms hit, the entire 19,000-ton structure would actually shudder. Think about that. Thousands of tons of stone vibrating under your feet.

Communication was basically non-existent. Before radio, they relied on passing ships or the occasional tender boat. Sometimes, if the weather was bad, the relief boat couldn't get near the rock for weeks. Keepers would run out of fresh food and be stuck with "the three S’s": salt pork, sea biscuits, and sadness. Well, maybe not the last one officially, but you get the point.

The Dangers of the "Whaling" Landing

Getting on and off the rock was the most dangerous part of the job. There was no dock. You couldn't just park a boat next to a rock that has 20-foot swells surging around it. Instead, they used a "Whaling" boom—a massive crane that swung a small boat or a "breeches buoy" (basically a life ring with pants) out over the churning water.

You’d be dangled in the air, praying the cable didn't snap, while the boat below tried to time the rise and fall of the waves. One wrong move and you were crushed against the granite or swept into the North Pacific current. In 1951, a tragedy occurred during a boat launch that claimed the lives of several Coast Guardsmen. It served as a grim reminder that even with modern technology, the reef remained undefeated.

Engineering the Impossible

The sheer scale of the St. George Reef Lighthouse is hard to wrap your head around without seeing the blueprints. The base isn't just a foundation; it’s a solid block of masonry designed to deflect the hydraulic force of the Pacific.

- The first layer consists of huge granite blocks, some weighing over several tons.

- These blocks were "interlocked" or dovetailed. This means they weren't just stacked; they were fitted together like a 3D jigsaw puzzle so they couldn't slide.

- The interior housed massive cisterns for fresh water—essential because you couldn't exactly dig a well in the middle of the ocean.

By the time it was finished, it had cost over $700,000. In 1892, that was a staggering amount of money. It was the most expensive lighthouse ever built in the United States at the time. Was it worth it? Most sailors would say yes. The light, powered by a massive first-order Fresnel lens, could be seen for 18 miles.

The lens itself was a masterpiece of glass and brass. It didn't just sit there; it floated on a bed of mercury so it could rotate with minimal friction. This allowed a relatively small clockwork mechanism to spin a lens that weighed as much as a small truck.

The Move to Automation and the End of an Era

By the 1970s, the Coast Guard was looking to cut costs. The St. George Reef Lighthouse was a logistical nightmare to maintain. In 1975, the light was officially decommissioned and replaced by a large navigational buoy.

The "Monster of the North" went dark.

📖 Related: Riu Palace Paradise Island Bahamas: What Nobody Tells You About the Modern Experience

For years, the structure sat abandoned. The salt air and bird droppings (mostly from cormorants who took over the place) began to eat away at the metalwork. It looked like the lighthouse was destined to crumble into the sea. However, a group of locals in Crescent City weren't having it. The St. George Reef Lighthouse Preservation Society was formed.

They’ve spent decades raising money and flying out to the rock via helicopter—the only safe way to get there now—to scrub walls, replace glass, and restore the living quarters. They even managed to get the light working again, though it’s now a solar-powered LED rather than the old kerosene-burning giant.

Why You Can't Just "Visit" St. George Reef

If you’re planning a road trip up Highway 101, don't expect to pull over and walk out to the light. It is strictly offshore.

You can see it from the shore at Pebble Beach in Crescent City on a clear day, but it looks like a tiny grey thumb on the horizon. To actually get on it, you usually need to be part of the preservation society or lucky enough to snag a spot on one of the rare, weather-dependent helicopter tours. These aren't your typical tourist excursions. They are expensive, and they get canceled constantly because the fog at the reef is no joke.

The lighthouse sits in one of the most productive—and dangerous—fishing grounds on the West Coast. The "Graveyard of the Giant" isn't just a nickname; the underwater topography around the reef creates weird currents and sudden breaking waves that still trip up experienced boaters today.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Lighthouse

A common myth is that the lighthouse was built on a natural island. It wasn't. Northwest Seal Rock was barely a rock—more like a jagged tooth that disappeared during storms. The "land" the lighthouse sits on is almost entirely man-made.

Another misconception is that the Fresnel lens is still in the tower. It actually isn't. The original first-order lens was removed and is now on display at the Del Norte County Historical Society Museum in Crescent City. If you want to see the scale of the engineering without risking a helicopter ride, go there. Standing next to that glass, you realize how much effort went into protecting sailors from a pile of rocks in the middle of nowhere.

Practical Steps for Lighthouse Enthusiasts

If you want to experience the St. George Reef Lighthouse today, you have to be strategic. You can't just wing it.

- Visit the Museum First: Start at the Del Norte County Historical Society. Seeing the lens up close gives you the context you need.

- Pebble Beach Lookout: Drive to the end of Pebble Beach Drive in Crescent City. Bring high-powered binoculars or a 600mm camera lens. Even then, it’s a distant view.

- Check the Preservation Society: Follow the St. George Reef Lighthouse Preservation Society (SGRPS) online. They are the ones who manage the restoration and occasionally organize flights.

- Study the Brother Jonathan: If you're a history buff, look into the shipwreck's recovery. Gold coins from the wreck were actually recovered in the 1990s, adding a "treasure hunter" layer to the lighthouse's grim history.

The lighthouse stands as a monument to a time when we didn't have GPS or satellite imaging. It was a time when the only thing between a ship and total destruction was a handful of men living in a stone tower, keeping a wick trimmed and a lens spinning through the worst weather the Pacific could throw at them.

It’s a brutal, beautiful piece of American history that reminds us how much we used to rely on human grit. It's not just a building; it's a 19,000-ton "thank you" to the sailors who never made it home. If you ever find yourself on the rugged coast of Northern California, take a moment to look out past the breakers. If the fog clears just right, you'll see it—still standing, still lonely, and still legendary.