Shigeru Miyamoto didn't just make a game in 1985. He basically built the blueprint for every digital world we’ve stepped into since. If you look back at Super Mario Bros 1 2 and 3, you aren't just looking at old pixels; you're looking at the DNA of modern movement, physics, and secrets. Most people remember the music and the mushrooms, but the actual technical leap between these three titles is honestly staggering when you realize they all ran on the same limited hardware.

It started with a plumber who was originally just "Jumpman" in Donkey Kong. By the time the third game rolled around, he was flying through the air in a raccoon suit. But the journey from point A to point C wasn't a straight line. It was messy. It involved a fake sequel, a dream world, and a theatrical play that changed everything we thought we knew about the Mushroom Kingdom.

✨ Don't miss: Riley Poppy Playtime Chapter 4: What Most People Get Wrong About Mob Entertainment's Next Villain

The 1985 Big Bang: Super Mario Bros 1

When Super Mario Bros. hit the NES, it killed the "single screen" era of gaming. Before this, you stayed in one box. Now, the screen scrolled. It felt like a journey.

The controls are what really changed the game. Most players don't realize that Mario’s movement in the first game is governed by a specific momentum physics engine that was revolutionary at the time. If you let go of the D-pad, he doesn't just stop. He slides. That friction—or lack thereof—is why the game still feels "slippery" to modern players used to the tighter controls of Super Mario World.

Here is the thing about the first game: it was a masterclass in invisible tutorials. Look at Level 1-1. You start on the left. A Goomba walks toward you from the right. There is nowhere to go but up. You jump, you hit a block, a mushroom comes out. It hits the pipe and bounces back toward you. You can't really avoid it. You get big. In thirty seconds, Miyamoto taught you everything without a single line of text.

The Identity Crisis of Super Mario Bros 2

Ask any fan about the second game and they’ll probably mention that it "isn't a real Mario game." That’s only half true.

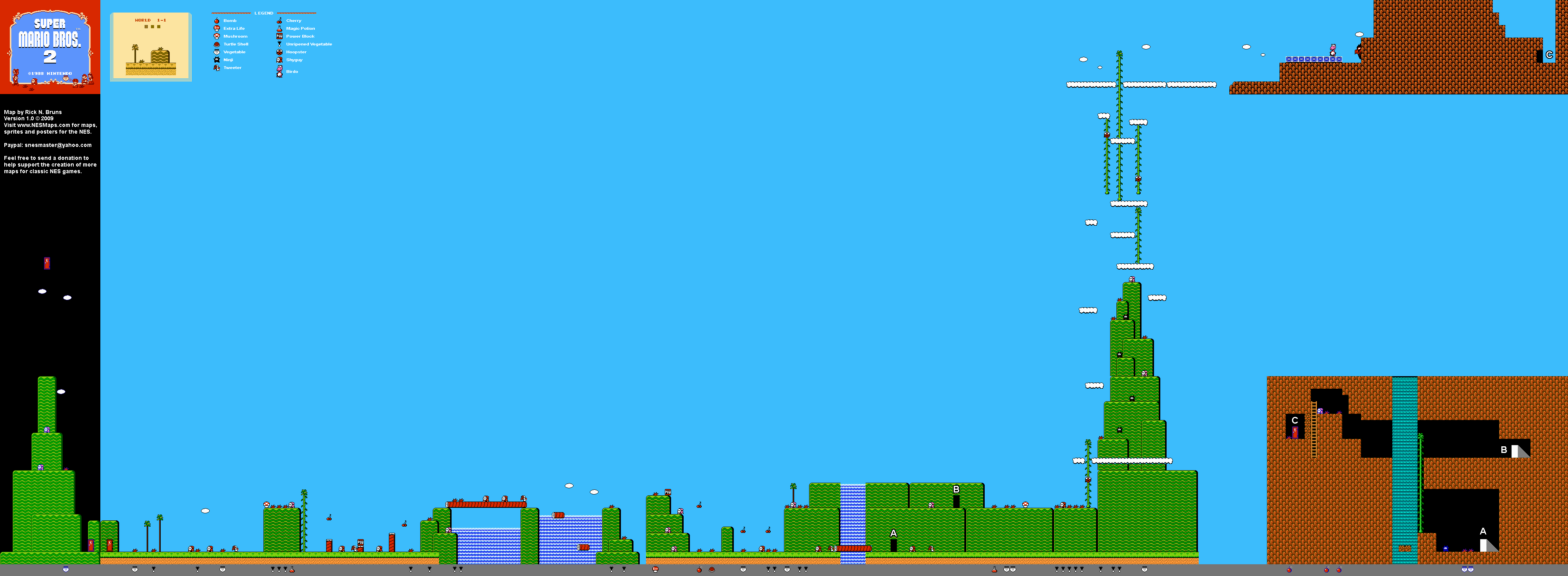

The version we got in the West was actually a re-skinned game called Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic. Nintendo of America thought the "real" Super Mario Bros. 2—known now as The Lost Levels—was way too hard for Americans. It was basically a ROM hack of the first game designed to punish players. So, they swapped the characters in Doki Doki Panic for Mario, Luigi, Peach, and Toad.

💡 You might also like: Why Oswald from Five Nights at Freddy's Into the Pit Is Actually Terrifying

Surprisingly, this "fake" game added more to the lore than the original. It gave us:

- Shy Guys and Birdo.

- The ability to pick up and throw enemies.

- Character-specific stats (Luigi’s high jump, Peach’s float).

- Bob-ombs.

It was weird. You pulled vegetables out of the ground instead of hitting blocks. You fought a giant frog named Wart instead of Bowser. But without this strange detour, the franchise would have stayed stagnant. It proved that Mario could exist outside of just jumping on heads.

Super Mario Bros 3 and the "Stage Play" Theory

If the first game was the spark, Super Mario Bros. 3 was the supernova. Released in 1988 (1990 in the US), it pushed the NES to its absolute breaking point. It used a special "MMC3" chip inside the cartridge to allow for diagonal scrolling and better memory management.

There’s a famous fan theory that Shigeru Miyamoto eventually confirmed in 2015: the entire game is a theatrical performance. Look at the opening. A curtain rises. Look at the platforms—they are bolted to the background with shadows. When you finish a level, you walk off-stage into the darkness.

This meta-narrative allowed for a wilder world. We got the World Map, which changed gaming forever. No longer were you forced down a linear path. You could choose to skip levels, play mini-games, or use an inventory system. The Warp Whistle—a direct shout-out to The Legend of Zelda—became the most hunted item in playground history.

The suits were the real star, though. The Tanooki Suit, the Frog Suit, and the Hammer Suit didn't just change your look; they changed the level design. Suddenly, developers had to account for players flying over the entire stage or swimming through heavy currents. It was a level of complexity that the NES shouldn't have been able to handle.

Why the Trilogy Still Dominates the Charts

You might wonder why people still care about Super Mario Bros 1 2 and 3 in an era of 4K graphics and ray tracing. It's because these games are "honest." There are no microtransactions. There are no 40-minute tutorials. You press Start, and you play.

Speedrunners are still finding "sub-pixels" and "frame-perfect" tricks in these games decades later. In the original Super Mario Bros., runners use "wall jumps" that the developers never intended, purely by exploiting how the game checks for collisions. In Mario 3, people have figured out how to "glitch" through pipes to reach the credits in under three minutes.

Technical Evolution at a Glance

In the first game, the backgrounds were mostly empty. Clouds and bushes were literally the same sprite, just colored differently. By the third game, we had scrolling parallax-style effects, animated water, and complex enemy AI like the Sun that chases you across the desert.

📖 Related: Ancient Copper Dragon MTG: Why This Card is Still the King of Commander Swing Turns

The jump in quality wasn't just artistic; it was an engineering feat. Nintendo programmers like Takashi Tezuka and Koji Kondo (who composed the iconic music) had to fit entire worlds into less memory than a single low-res JPEG takes up today.

Actionable Tips for Modern Players

If you’re going back to play these on the Nintendo Switch Online service or original hardware, keep these things in mind to actually enjoy the experience:

- Understand the "Crouch-Slide" in Mario 3: You can keep your "P-Wing" meter full longer by jumping and then tapping the run button rhythmically rather than holding it down.

- The "Infinite Lives" Trick is Real: In the first game, on Level 3-1, you can trap two Koopas on the stairs at the end. If you time your jumps right, you can bounce on them indefinitely to max out your lives. Just don't go over 128 or the game's code will overflow and give you a "Game Over."

- Warp to the End: In Mario 3, you can get two Warp Whistles in the very first world (one in 1-3 by crouching on a white block, and one in the Fortress). This lets you skip straight to the final world if you aren't feeling the grind.

- Don't Sleep on Peach in Mario 2: Her floating ability is basically a "cheat mode" for difficult platforming sections. It changes the entire difficulty curve of the game.

The legacy of the NES trilogy is about more than just nostalgia. It’s about how a small team of creators took a grey toaster-shaped box and used it to define what "fun" looks like for the entire world. Whether it's the tight platforming of the first, the weirdness of the second, or the sheer scale of the third, these games remain the gold standard for game design.

Stop looking at them as museum pieces. Go play them. Most modern games still can't match the "feel" of a perfectly timed jump in World 1-1.

Next Steps for Retro Mastery

To truly master the trilogy, start by practicing "low-jump" techniques in the original game to save time on animations. Once you've handled the physics there, move to Super Mario Bros. 3 and focus on "P-speed" management, which is the key to uncovering the game's most vertical secrets. If you're looking for a challenge, try a "No-Warps" run of the third game; it reveals just how massive and creative the level design truly was for 1988 hardware.