You've probably seen them. Those little files with an arrow on the icon, or the ones that show up with a weird @ symbol when you run a ls -F command in your terminal. They’re everywhere in the Linux ecosystem, from your /bin folder to the complex depths of your Python virtual environments. We’re talking about symbolic links in linux. Honestly, most people just call them symlinks. If you've ever moved a massive folder to a secondary hard drive but needed the software to think it was still in the original spot, you've used one. Or you should have.

They are basically pointers. Think of a symlink as a signpost. It isn't the destination itself; it just tells the operating system, "Hey, the data you're looking for is actually over there."

But here is the thing.

People mess them up constantly. They create circular loops that crash scripts. They delete the source file and wonder why the link turned red and "broke." Understanding how these tiny files function is the difference between a clean, organized server and a filesystem that looks like a bowl of digital spaghetti.

The Absolute Basics of Symbolic Links in Linux

At its core, a symlink is a special type of file that contains a text string. That string is the path to another file or directory. When you try to open the symlink, the Linux kernel sees that it's a link and transparently redirects the operation to the target. It's subtle. You don't even realize it's happening most of the time.

Contrast this with a "hard link." A hard link is a much more rigid beast. It’s an additional name for the exact same data on the disk (the same inode). If you delete the original file name, the data stays put as long as one hard link still exists. Symlinks don't work like that. They are fragile. If the "target" file is deleted, the symlink becomes "dangling." It’s a road sign pointing to a house that was demolished yesterday.

How to actually make one without breaking things

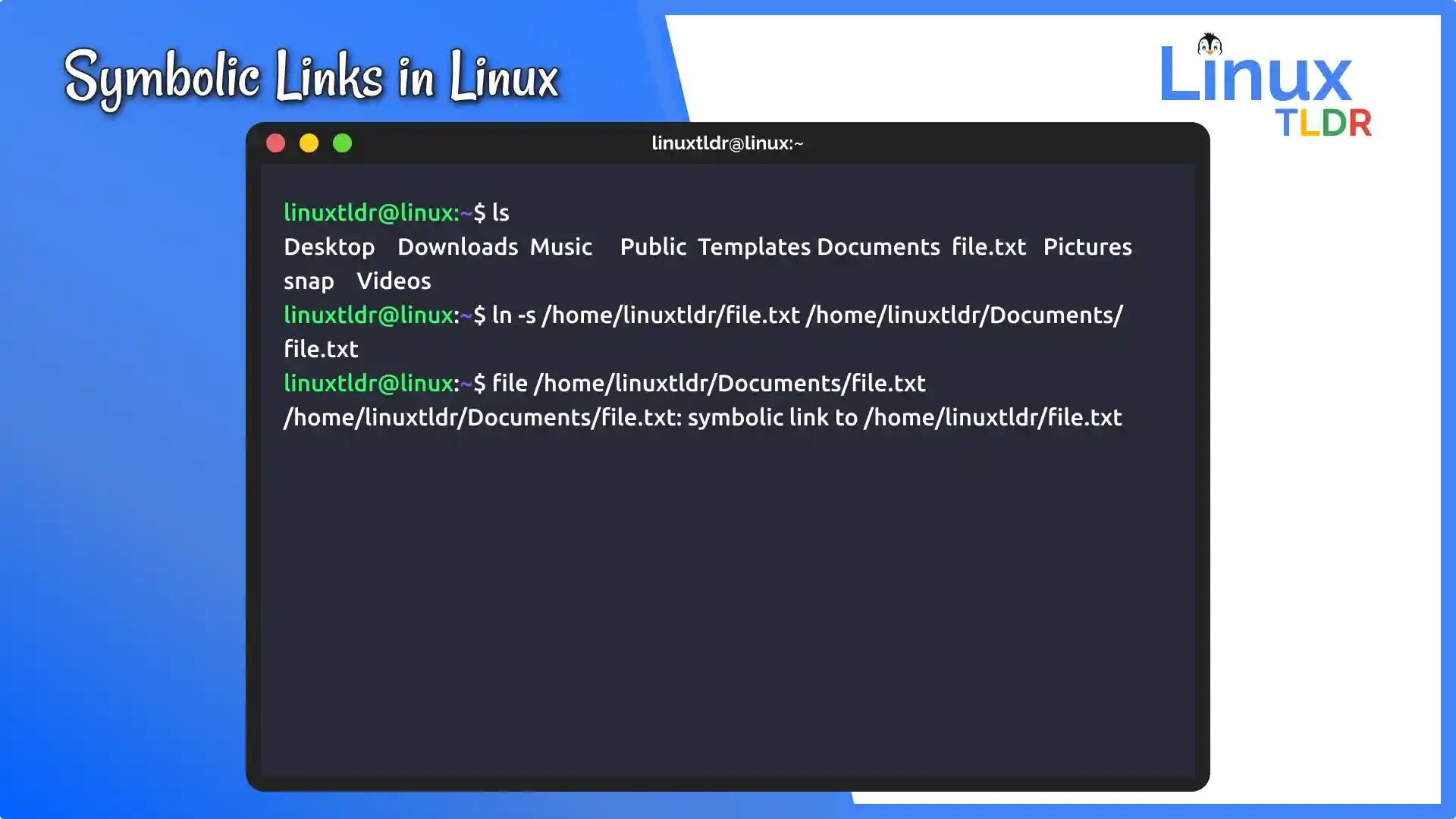

The command is simple, but the order of arguments trips everyone up. It's ln -s [TARGET] [LINK_NAME].

If you want to link your massive projects folder to your home directory, you'd type:ln -s /mnt/data/projects ~/projects

If you swap those? You just created a link inside your data folder pointing back to your home. It's a mess. Use absolute paths whenever possible. Relative paths work, sure, but they are calculated based on the location of the link, not where you are standing when you type the command. This is exactly how people end up with broken links when they move the symlink to a different folder later on.

Why We Use Them (And Why You Should Too)

Why not just copy the file? Because duplication is the enemy of sanity.

Imagine you are managing a web server. You have version 1.2 of an application. Then you upgrade to version 1.3. Instead of changing every single configuration file in your system to point to the new folder, you just point a symlink named current to the v1.3 directory. When version 1.4 comes out, you update the link. Done. Zero downtime, zero hunting through config files for hardcoded paths. This is exactly how tools like Nginx or the Debian alternatives system manage different versions of Java or Python.

- Space saving: Symlinks take up virtually zero bytes.

- Version control: Swapping versions is as fast as a single command.

- Organization: You can keep your system files on a fast SSD and your bulky logs on a cheap HDD, linked seamlessly.

The "Dangling" Problem

We've all been there. You run ls -l and see a file glowing red in your terminal. That’s a dead link. Linux doesn't check if the target exists when you create the link. It’s a "trust but don't verify" system.

You can find these broken remnants easily with a bit of "find" magic:find . -type l ! -exec test -e {} \; -print

This command basically asks the system: "Find all links, and if the file they point to doesn't exist, tell me." It’s a lifesaver when you're cleaning up a messy home directory after a big project.

Hard Links: The Stoic Older Brother

I mentioned hard links earlier. Let's get into the weeds for a second. Every file on a Linux filesystem has at least one hard link—the filename itself. When you create another hard link, you aren't creating a shortcut. You are creating a second identity for the data.

There are two massive limitations here that usually make symbolic links in linux the better choice:

- Hard links cannot span across different partitions or disks. Because they reference a specific "inode" (a physical address on the disk), they are trapped on that specific drive.

- You generally cannot create hard links for directories. It prevents the system from getting stuck in infinite recursive loops, which would make backups a nightmare.

Symlinks don't care about these rules. They'll point to a network drive, a USB stick, or a directory three levels up. They are flexible.

✨ Don't miss: Spark Plug Thread Insert: How to Save Your Engine Without Pulling the Head

Security Concerns You Probably Ignored

Software developers like Dan Bernstein (creator of qmail) have historically pointed out the "symlink race condition." It sounds technical, but it's basically a trick. If a program (especially one running as root) is about to write to a temporary file, a malicious user could quickly create a symlink with that same name, pointing to /etc/shadow or some other critical file. The program might then accidentally overwrite system secrets.

Modern Linux kernels have protections against this (like fs.protected_symlinks), but it’s a reminder that these "simple shortcuts" are powerful tools that interact deeply with the kernel's permission logic.

Common Pitfalls and "Gotchas"

Permission handling is weird. If you check the permissions of a symlink, they often appear as lrwxrwxrwx. Does that mean everyone has full access? No. The permissions on the symlink itself are almost always ignored. What matters are the permissions on the target file.

Also, consider the rm command.

If you want to delete a symlink to a folder, type rm my_link.

Do NOT type rm my_link/.

That trailing slash tells Linux you want to go through the link and start deleting the contents of the actual folder. People have wiped out entire databases because of one accidental forward slash. Be careful.

Real World Example: The Python Problem

Python developers use symlinks every day without knowing it. When you create a virtual environment (venv), the python binary inside that folder is often just a symlink to the main system Python. This allows the virtual environment to be lightweight. If you move your system Python, your environments break. This is why "broken symlinks" is one of the top search results for Python environment troubleshooting.

Actionable Next Steps for Mastering Links

If you want to actually get comfortable with this, stop using the GUI for a day. Get into the terminal and try these:

- Map out your system: Run

ls -la /etc/alternativesto see how Linux manages different versions of software using a massive web of symlinks. It's eye-opening. - Audit your folders: Use the

findcommand mentioned earlier to see if you have dead links cluttering your workspace. - Practice relative vs absolute: Create a link using a relative path, then move that link to a different folder. Watch it break. Then recreate it using an absolute path (starting with

/) and move it again. It'll still work. That's the lesson. - Use

readlink -f: If you ever get lost in a chain of links (a link pointing to a link pointing to a link), runreadlink -f [filename]to cut through the noise and see the final, actual destination.

Symbolic links are a fundamental building block of the "Everything is a file" philosophy in Linux. They provide a level of filesystem abstraction that Windows shortcuts can only dream of. Once you stop fearing the "broken link" and start using them to architect your data, you'll find that managing a Linux system becomes significantly more logical. Just watch out for those trailing slashes.