Nikola Tesla is basically the patron saint of the "ahead of his time" club. Everyone knows the AC motor or the Tesla coil, but he had this weird obsession with fluids too. In 1920, he patented something called a "valvular conduit." Most of us just call it the Tesla one way valve.

It’s a valve. But it has zero moving parts. No springs, no flaps, no rubber seals that inevitably rot and leak. Honestly, if you look at a cross-section of it, it looks more like a piece of tribal art than a piece of high-end engineering. It’s just a series of teardrop-shaped loops and clever little bypasses.

How the Tesla one way valve actually works (without breaking)

Most check valves use a physical barrier. Think of a swinging gate. Fluid goes one way, the gate opens; fluid tries to go back, the gate slams shut. Simple, right? But moving parts are a liability. They wear out. They get stuck.

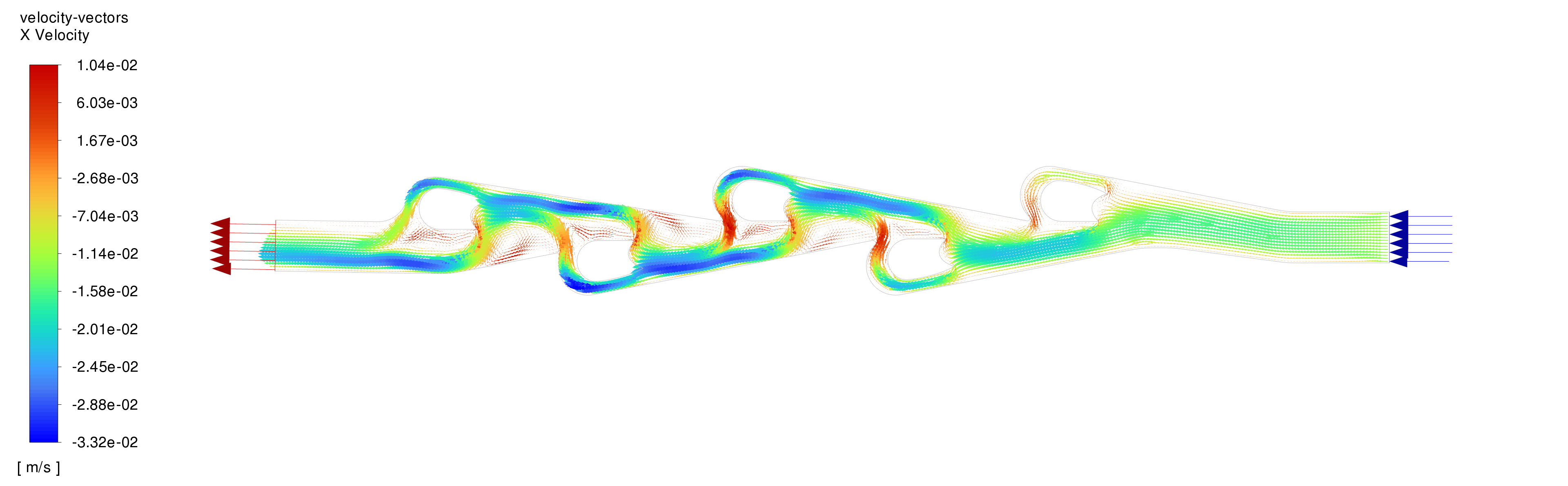

The Tesla one way valve uses geometry instead of mechanics. When fluid flows in the "easy" direction, it mostly stays in the center channel. It’s a smooth ride. But when the fluid tries to reverse? That’s where things get chaotic.

The design forces the reversing fluid to split. Part of it gets diverted into those side loops I mentioned. By the time that diverted fluid loops back around, it's heading straight into the teeth of the main flow. They crash into each other. This creates massive turbulence and "chokes" the flow. Tesla himself claimed in his patent that you could get a pressure ratio of about 200, making it act like a "slightly leaking valve" without ever needing a single moving part.

Why 2026 is obsessed with a 1920 patent

You’d think a century-old invention would be in a museum, not in cutting-edge tech. Wrong. We are seeing a massive resurgence in this design because of two things: microfluidics and extreme environments.

📖 Related: Centric Fiber Customer Service: What People Actually Say After They Call

Take hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Dealing with high-pressure hydrogen is a nightmare for traditional valves because hydrogen molecules are tiny and destructive. Researchers have been testing Tesla one way valve structures for hydrogen decompression. Why? Because you can’t break a shape. If the valve is just a series of channels carved into a block of steel, it can handle insane pressures and temperatures that would melt a standard rubber seal.

- Microfluidics: In tiny chips used for medical diagnostics, you can’t exactly put a microscopic swinging hinge in a tube the size of a human hair. You just etch the Tesla pattern into the silicon.

- Space Tech: Moving parts are a point of failure in rockets. Engineers are looking at these valves for "Rotating Detonation Engines" (RDEs) where the explosions happen thousands of times per second.

- Phones: A few years back, Xiaomi started messing with "Loop Liquid Cooling." They used a version of this valve to keep the coolant moving in one direction around the hot processor.

The "Diodicity" Problem

Engineers use a fancy word for how well these things work: diodicity. Basically, it’s a ratio. You compare the resistance of the flow going the wrong way to the flow going the right way.

Here is the catch. In a steady, slow flow—like a garden hose—the Tesla valve is actually kinda mediocre. It doesn't "slam shut." It just resists. For a long time, people thought Tesla was exaggerating how good it was.

But a 2021 study in Nature Communications changed the game. They found that if you pulse the flow—making it vibrate or oscillate—the Tesla one way valve becomes incredibly efficient. It turns out Tesla wasn't designing it for a steady stream of water; he was designing it for the vibrating, pulsing world of high-speed machinery. When the fluid pulses, the turbulence in those side loops kicks in much faster. It acts like a "fluidic diode," turning shaky, back-and-forth energy into a smooth, one-way stream.

It’s not a perfect fix for everything

Don't go ripping the check valves out of your home plumbing just yet. These things take up a lot of space compared to a tiny ball valve. To get real "blocking" power, you need to chain several of these stages together. One loop might not do much, but eleven loops? Now you're talking.

Also, they are "leaky." If you need a 100% airtight seal to keep your basement from flooding, a Tesla one way valve won't do it. There will always be a tiny bit of bypass. It’s meant for systems where reliability and "no maintenance" are more important than a perfect seal.

Practical Insights for the Modern Engineer or Hobbyist

If you're looking into using this design, keep these realities in mind:

- Fabrication is the key. These used to be hard to make. Now, with high-precision 3D printing and CNC milling, you can "print" a Tesla valve inside a solid block of metal or plastic.

- Scale matters. They work exceptionally well at the "micro" level where surface tension and laminar flow rule the day.

- Think about the pulse. If your system has natural vibrations—like an engine or a pump—the Tesla valve will perform way better than it would in a static pressure test.

The Tesla one way valve is a reminder that sometimes the best way to solve a mechanical problem isn't to add more parts, but to use the ones you have more cleverly. We are finally catching up to what Tesla realized in 1916: the shape of the container is just as important as the fluid inside it.

If you are building a high-temperature system or a micro-scale project where a traditional valve would just fail or be impossible to build, looking at the original Patent No. 1,329,559 is genuinely the best place to start. The math has been updated, but the "valvular conduit" geometry is still the gold standard for solid-state fluid control.