You’re looking up, squinting against the sun, and you see it. A tiny, silver or white dot drifting lazily across the blue. It’s not a bird. It’s definitely not a plane. Your brain probably jumps to "UFO" or maybe "spy craft" thanks to the headlines we've seen over the last few years, but honestly? It’s almost certainly just a weather balloon in the sky. These things are launched twice a day, every single day, from about 900 locations around the globe. Simultaneously.

It’s a massive, coordinated effort that’s been happening since the 1930s.

Why? Because satellites, for all their billion-dollar optics, suck at measuring the exact "flavor" of the air. They can see clouds, sure. They can guess at temperatures based on infrared. But if you want to know exactly how much moisture is sitting at 30,000 feet or the precise wind shear that might tear a thunderstorm apart, you have to actually go there. You have to touch the air.

The Anatomy of a High-Altitude Drifter

A weather balloon isn't just a big party favor. It’s a sophisticated, sacrificial lamb for science.

When it starts its journey on the ground, it looks kind of pathetic. It’s a limp, latex or neoprene bag, maybe six feet wide, filled with hydrogen or helium. But as it rises, the physics get weird. Because the air pressure outside the balloon drops as it climbs, the gas inside expands. By the time that weather balloon in the sky reaches its peak altitude—roughly 100,000 feet, which is three times higher than a commercial jet—it has stretched into a massive, translucent sphere the size of a small house.

Hanging below this growing giant is the real star of the show: the radiosonde. This is a small, white plastic box packed with sensors. It’s basically a disposable weather station. Inside, you’ve got a thermistor for temperature, a hygristor for humidity, and a pressure sensor. It’s also got a GPS antenna, which is how meteorologists track wind speed and direction. If the box is moving 50 knots to the east, well, so is the wind.

Why We Still Use "Old" Tech in 2026

You’d think we’d have replaced this by now. We haven't.

The National Weather Service (NWS) in the United States and organizations like the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) rely on these vertical "profiles" of the atmosphere. Computer models are hungry for data. If you feed a model "bad" or "thin" data about what the upper atmosphere looks like, the forecast for a week from now will be total garbage.

- Vertical Resolution: Satellites look down through the whole atmosphere at once. Balloons take a "core sample."

- Cost Efficiency: A radiosonde costs a few hundred bucks. A satellite costs hundreds of millions.

- The Pop: Eventually, the balloon expands so much that the latex reaches its elastic limit. It bursts. A small orange parachute opens, and the sensor box drifts back to Earth.

Most of these sensors are never found. They land in forests, oceans, or cornfields. While the NWS used to include mail-back bags, most modern units are considered "single-use," though some hobbyists make a sport out of "radiosonde hunting" using radio direction-finding gear to track them as they fall.

The "Spy Balloon" Confusion

We have to talk about the elephant in the room. Or rather, the giant white orb in the stratosphere.

In early 2023, the world went nuts over a Chinese high-altitude balloon that crossed North America. This caused a massive spike in people reporting every weather balloon in the sky as a national security threat. There is a difference, though. A standard meteorological balloon is small, travels with the wind, and stays up for maybe two hours.

🔗 Read more: Why Dark Side of the Moon Pics Still Look So Weird After 60 Years

Research or surveillance balloons are different beasts. They are often "super-pressure" balloons. They don't burst. They can stay at a constant altitude for weeks or even months by venting gas or using ballast. If you see something that stays in the same spot for three days, it’s not your local weatherman's balloon. It’s something much more complex—likely a long-duration research project from NASA’s Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility or a private telecom experiment.

The Life Cycle of a Launch

Every day at 12:00 UTC and 00:00 UTC, technicians at places like the Brookhaven National Laboratory or small outposts in Alaska go outside. They check the wind. They fill the balloon. They let go.

The ascent takes about 90 to 120 minutes. During that time, the radiosonde is screaming data back to a ground station via radio frequency (usually around 400 MHz). This data is then fed into the Global Telecommunication System (GTS).

It’s a bit of a miracle of international cooperation. Even countries that don't get along politically still share their balloon data. Why? Because the weather doesn't care about borders. A cold front over Canada today is a freeze in Florida tomorrow. Without that weather balloon in the sky over the Yukon, the orange farmers in Orlando are flying blind.

Common Misconceptions (What People Get Wrong)

People often think these things are dangerous to planes. They aren't.

The latex is incredibly thin, and the radiosonde is designed to be lightweight (usually under 200 grams). If a jet engine sucked one in, it would be like a bird strike, but even less "solid." The FAA has strict rules about where and when they can be launched, but generally, they are the ghosts of the airways.

Another weird one: "The government is using them for cloud seeding." No. Cloud seeding usually requires planes or ground-based silver iodide generators. A weather balloon is a thermometer with a hobby for heights. That’s it.

How to Spot One and What to Do

If you’re a weather nerd or just curious, you can actually track these things in real-time.

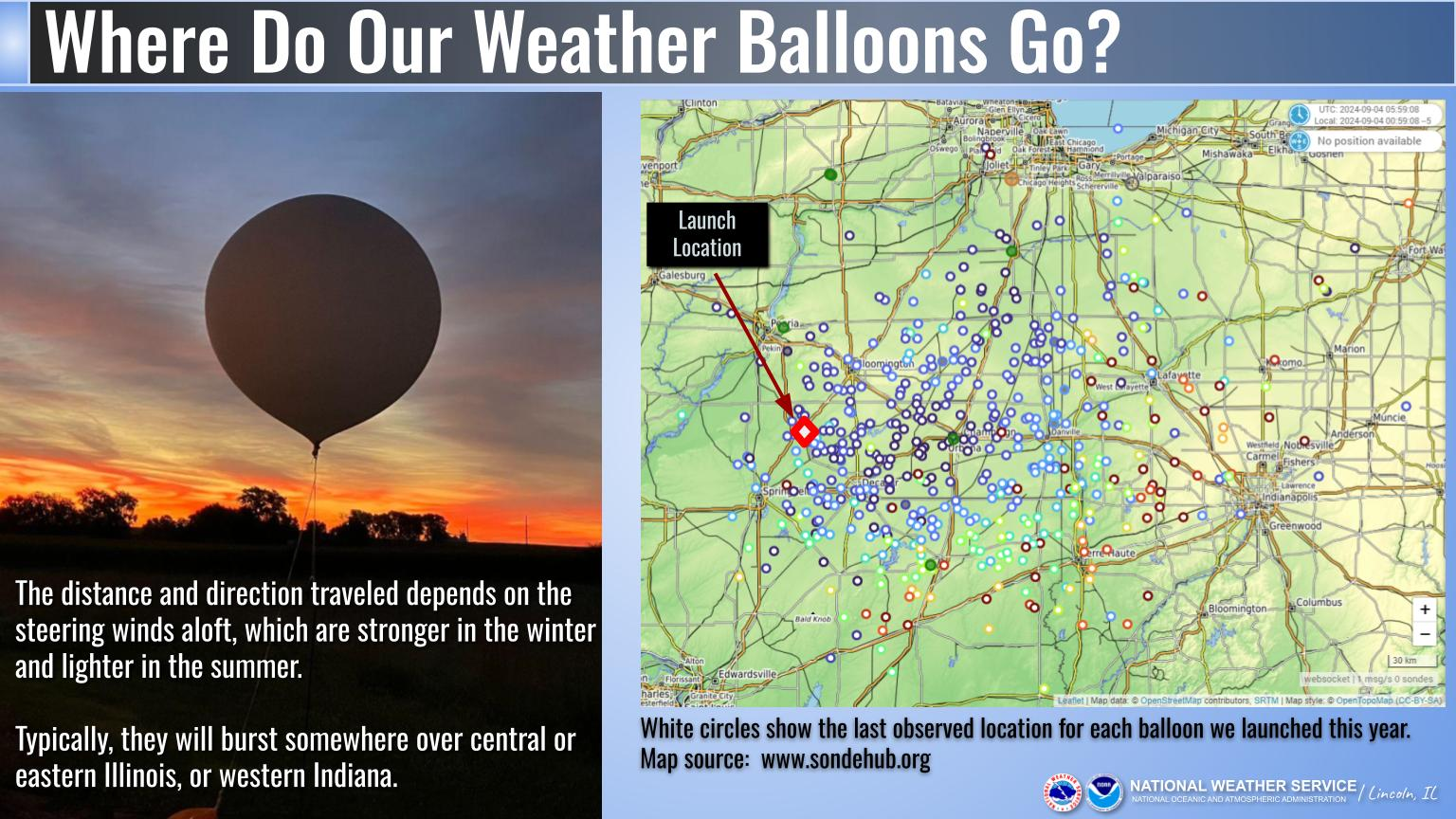

- Check the Map: Websites like SondeHub show live tracks of balloons currently in the air. You can see their altitude, their predicted burst point, and where they are likely to land.

- Look for the "Twinkle": Late afternoon or early morning is the best time. Because the balloon is so high up, it can still be hit by sunlight even after the sun has set for you on the ground. It will look like a bright, unmoving star that slowly drifts.

- If You Find One: Don't panic. It's not a bomb. Most modern radiosondes have instructions printed on the side. Usually, you can just dispose of it in the trash, but some universities or research groups might have a "Reward if Found" sticker.

Practical Steps for the Curious

If this actually interests you, don't just stare at the sky.

- Download a tracking app: Search for "SondeHub" or "Radiosonde Tracker." It turns the sky into a scavenger hunt.

- Visit a Launch: Many NWS offices used to allow public viewings of the launches. Post-2020, rules vary, but it's worth a call to your local office if you're near a launch site.

- Build Your Own: You can actually buy "Weather Balloon Kits" online. However, be warned: you need to follow FAA Part 101 regulations. You can't just launch whatever you want into commercial airspace without checking the rules first.

The next time you see that strange, shimmering weather balloon in the sky, remember it's not a secret mission. It’s just a little plastic box doing the hard, lonely work of making sure you know whether or not to bring an umbrella to work tomorrow.

It's a low-tech solution to a high-tech problem, and honestly, it’s one of the few things in science that still works exactly the way it did eighty years ago because the physics haven't changed. The air is still there, and someone still needs to go up and touch it.