History isn't just about kings and old treaties; it's about the grit, the grease, and the sheer audacity of people who decided to bend the physical world to their will. When we talk about the 7 wonders of the industrial world, we aren't just looking at pretty architecture. We are looking at machines and structures that basically redefined what it means to be human. Think about it. Before the SS Great Eastern or the Panama Canal, the world was massive, disconnected, and slow. If you wanted to get somewhere, you prayed the wind held or your horse didn't throw a shoe. Then, everything changed.

People often get these confused with the ancient wonders, but there’s a massive difference. The pyramids were built to house the dead. The industrial wonders were built to move the living, power the planet, and shrink the globe. They are loud, dangerous, and kind of terrifying if you look at the death tolls.

Honestly, the "Industrial World" label usually points back to the 2003 BBC series that popularized this specific list. It covers the 19th and early 20th centuries—that sweet spot where steam and steel became the new gods. These projects weren't just "big." They were considered impossible. They broke banks, killed thousands of laborers, and ruined reputations. But they stood. They’re still standing, mostly.

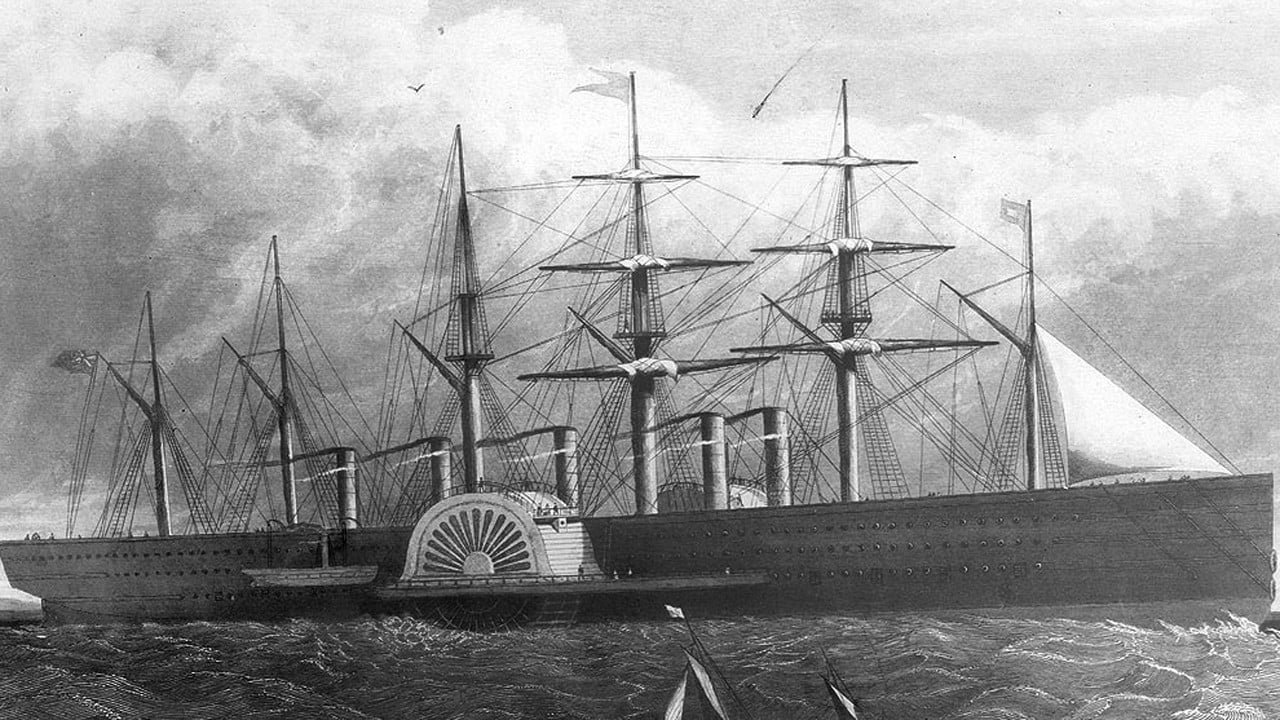

The SS Great Eastern: Brunel’s "Great Iron Ship"

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was a genius, but he was also a bit of a madman. He wanted to build a ship so big it wouldn't need to refuel between England and Australia. Simple, right? Not in 1858. The 7 wonders of the industrial world starts here because the Great Eastern was a freaking behemoth—six times larger than any ship ever built at the time. It had five funnels and six masts. It was basically a floating city made of iron.

The launch was a total disaster. It got stuck on the slipway for three months. It bankrupt the company. People called it a white elephant. But here’s the thing: while it failed as a passenger liner, it ended up doing something much cooler. It laid the first successful transatlantic telegraph cable. Suddenly, London could "talk" to New York in minutes instead of weeks. Imagine the whiplash of that technological jump. One day you’re waiting for a ship to bring news, the next day, it’s just there on a wire.

🔗 Read more: Why the fake moon landing debunked theories still haunt the internet (and the proof that kills them)

The Bell Rock Lighthouse: Fighting the Sea

Building a tower in the middle of the North Sea sounds like a suicide mission. Robert Stevenson (grandfather of the guy who wrote Treasure Island) decided to do it anyway. The Bell Rock is a reef that was sinking ships left and right, but it was underwater for almost the entire day. His crew could only work for a few hours at low tide.

It took four years. They lived on a floating ship nearby that tossed and turned in the freezing waves. If the tide came in too fast, they were dead. They used interlocking stones that fit together like a 3D jigsaw puzzle so the waves couldn't knock them over. It was finished in 1811 and hasn't been rebuilt since. That is almost 215 years of North Sea storms hitting it, and it hasn't budged. That’s not just engineering; that’s a miracle of masonry.

The Brooklyn Bridge: A Family Obsession

New York wouldn’t be New York without this bridge. But the story is actually kinda tragic. John Roebling designed it, then his foot got crushed by a ferry and he died of tetanus before they even broke ground. His son, Washington Roebling, took over but got "the bends" from working in the pressurized caissons underwater. He ended up paralyzed, watching the construction through a telescope from his bedroom window.

So, who actually built it? Emily Roebling, Washington’s wife. She basically became the first woman field engineer, relaying instructions between her husband and the workers for over a decade. When it opened in 1883, it was the longest suspension bridge in the world. People were so scared it would collapse that P.T. Barnum eventually marched 21 elephants across it just to prove it was safe.

The London Sewerage System: The Great Stink

This is the least "glamorous" of the 7 wonders of the industrial world, but arguably the most important. In the summer of 1858, London smelled so bad from raw sewage in the Thames that Parliament had to drape curtains soaked in lime over their windows just to breathe. They called it "The Great Stink."

Joseph Bazalgette was the man with the plan. He designed 82 miles of main intercepting sewers and 1,100 miles of street sewers. He was obsessed with quality. He used Portland cement, which was new at the time, and he made the pipes much larger than they needed to be. He basically said, "We’re only doing this once." Because he over-engineered it, the system still handles most of London’s waste today. He literally saved millions of lives from cholera. If you live in a city and don't have dysentery, thank Bazalgette.

The First Transcontinental Railroad: Shinking a Continent

Before 1869, getting from New York to San Francisco took six months. You either went by wagon (dangerous), or by ship around South America (expensive and also dangerous). The railroad changed that to six days.

It was a race between two companies: the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific. They met at Promontory Summit, Utah. It was brutal work. The Central Pacific had to blast through the Sierra Nevada mountains using nitroglycerin, which is incredibly unstable. Thousands of Chinese immigrants did the hardest, most dangerous work for lower pay than their white counterparts. It was a feat of logistics that basically unified the United States, but it came at a massive human and environmental cost.

The Suez Canal: The Shortcut to India

The French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps convinced the Egyptian khedive to let him dig a hole between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. It sounds simple, but it was a 100-mile trench through the desert. No locks. Just a straight sea-level ditch.

It took ten years. They started with forced labor (corvée labor) using shovels and baskets, but eventually transitioned to massive steam-powered dredgers. When it opened in 1869, it cut 4,500 miles off the trip from Europe to Asia. You didn't have to go around Africa anymore. It turned the Mediterranean back into the center of the world's trade map. It’s still one of the most vital arteries of global commerce—just ask the guys who got that "Ever Given" ship stuck a few years ago.

The Panama Canal: Defeating the Jungle

This was the "Moonshot" of the early 1900s. The French tried it first and failed miserably. They lost 22,000 men, mostly to yellow fever and malaria. They thought they could build a sea-level canal like Suez, but Panama has mountains and a massive river that floods.

The Americans took over in 1904. Chief Engineer John Stevens realized they had to build a "bridge of water"—a system of locks that would lift ships over the mountains. They also had to wage war on mosquitoes. Dr. William Gorgas realized mosquitoes carried the diseases, so they spent millions on mosquito nets and draining swamps. It worked. They moved enough earth to bury Manhattan under 12 feet of dirt. It opened in 1914, just as WWI started. It remains a masterclass in hydraulic engineering.

What We Get Wrong About These Wonders

People think these were built by "visionaries" who knew exactly what they were doing.

Actually?

Most of them were guessing. They were using materials they didn't fully understand and math that was still being developed. Brunel didn't know if the Great Eastern would actually float. Bazalgette didn't know if Portland cement would hold up. They took massive risks that wouldn't be allowed under modern safety regulations.

Another misconception is that these are just "relics." Look at the Panama Canal or the London sewers. These aren't museum pieces. They are working infrastructure. We are still living in the world these Victorian engineers built. We’ve added computers and sensors, but the bones of the global economy are still made of 19th-century iron and concrete.

Why This History Matters for You Today

If you're looking for lessons from the 7 wonders of the industrial world, it's not about the "glory of empire." It's about problem-solving at scale.

- Over-engineer for the future: Bazalgette built bigger pipes than he needed, and they saved London for two centuries. When you build something, don't just build for today's capacity.

- Infrastructure is health: The sewers did more for human life expectancy than almost any medical breakthrough.

- Logistics wins: The Suez and the Railroad didn't just move goods; they moved ideas and culture. The "network effect" started in the 1800s.

Next Steps for History and Tech Buffs

To really understand how these shaped our world, you should check out the original 2003 BBC documentary Seven Wonders of the Industrial World—it’s based on Deborah Cadbury’s book, which is also a fantastic read. If you’re ever in London, go to the Thames Barrier or the Crossness Pumping Station. Seeing the "Cathedral of Sewage" in person makes you realize how much art went into these functional monsters.

If you want to dive deeper into the engineering side, look up the "Great Projects" archives at the Library of Congress. It’s wild to see the original hand-drawn blueprints for the Brooklyn Bridge and realize they did all that without a single calculator.

Check your local museum's digital archives for "Industrial Revolution" exhibits. Many offer VR tours of these sites now. It's the best way to feel the scale without getting covered in 19th-century coal dust.