The moon is a death trap. Honestly, if you look at the physics of it, humans had no business being there in 1969. We were riding on top of a controlled explosion, sitting in a craft that was basically a high-tech thermos. That thermos was the command and service module, or the CSM if you’re into NASA acronyms. While the Lunar Module got all the glory for actually touching the dust, the CSM was the real MVP of the Apollo program. It was the only part of the stack that had to work perfectly from launch to splashdown, or everyone died. Simple as that.

Think about the sheer audacity of the design. North American Aviation—now part of Boeing—had to build a vehicle that could withstand the vacuum of space, the blistering heat of direct solar radiation, and the 5,000-degree inferno of atmospheric reentry. All with less computing power than the chip in your electric toothbrush.

What the Command and Service Module Actually Was

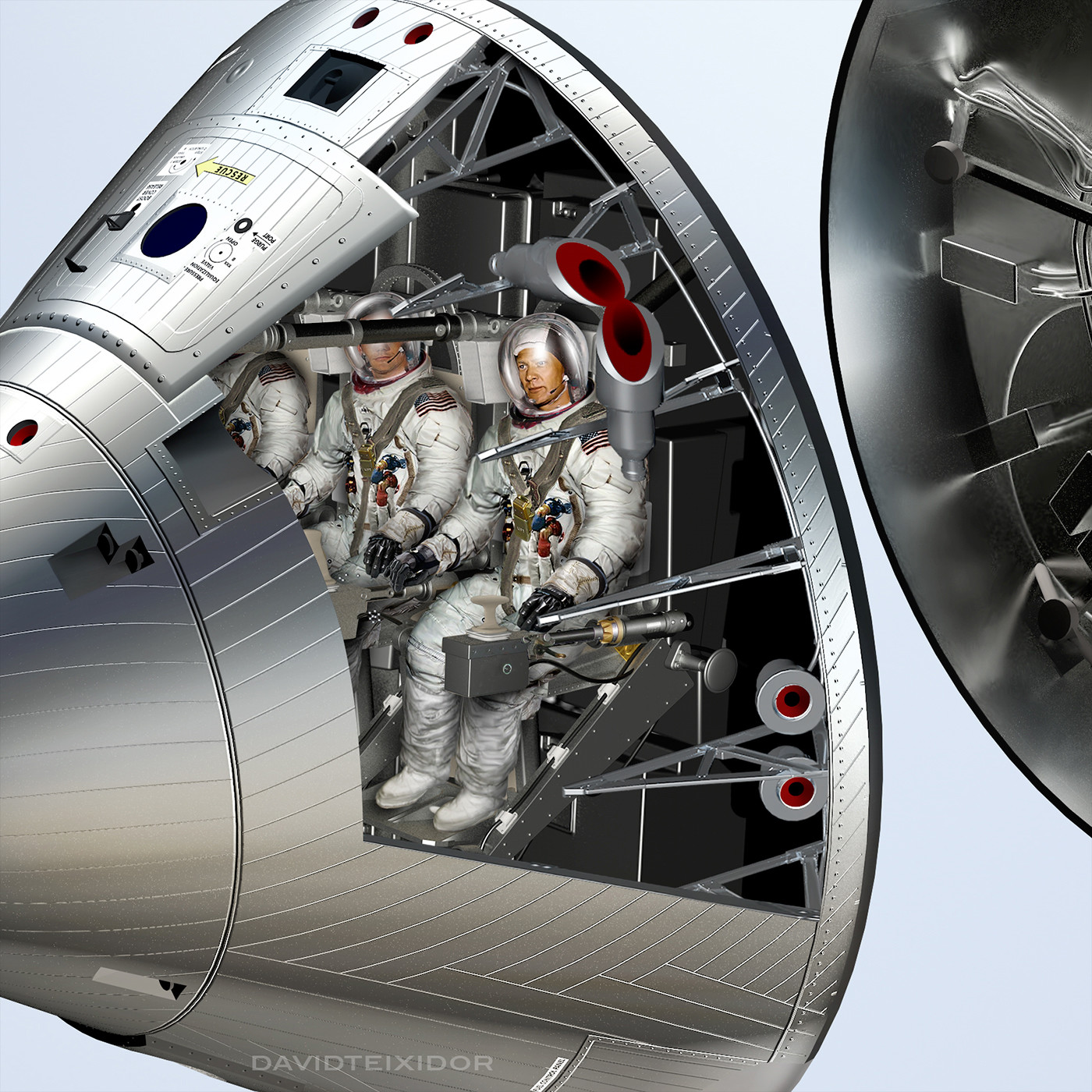

The CSM wasn't just one thing. It was two distinct components joined at the hip. You had the Command Module (CM), which looked like a giant blunt cone, and the Service Module (SM), a big unpressurized cylinder that sat behind it.

The CM was the brain and the bedroom. It’s where Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins spent their days cramped together in a space about the size of a large walk-in closet. People always imagine it being roomy. It wasn't. Once you factor in the control panels, the storage lockers, and the three couches, you had about 210 cubic feet of habitable volume. Imagine living in a car with two of your friends for eight days without a shower. That’s Apollo.

Then you have the Service Module. This was the powerhouse. It carried the oxygen, the water, the fuel cells, and most importantly, the Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine. The SM was the muscle that got them into lunar orbit and, more critically, gave them the "kick" to get back home. Without that engine firing, they’d just be orbiting the moon until the oxygen ran out.

The Block I vs. Block II Disaster

We have to talk about the fire. If you want to understand the command and service module, you have to understand the transition from Block I to Block II.

The original design, Block I, was never meant to land on the moon. It was for Earth orbit testing. But it had a fatal flaw: a hatch that opened inward. When a spark ignited the pure oxygen atmosphere during a ground test in 1967, the pressure built up so fast the astronauts—Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee—couldn't pull the hatch open. They were gone in seconds.

NASA basically had to tear the whole thing down and start over.

The Block II CSM was a different beast. It had the outward-opening "quick release" hatch. It had fireproof materials like Beta cloth. It also had the docking probe at the nose, which allowed it to link up with the Lunar Module. Block I couldn't even do that. It’s a grim reality of engineering: sometimes you need a catastrophe to force the design changes that actually make a mission survivable.

The SPS Engine: The Scariest Part of the Trip

The Service Propulsion System engine was arguably the most reliable piece of machinery ever built. It had to be. It didn't have a backup.

Most rocket engines use complex igniters, but the SPS used hypergolic propellants—Aerozine 50 and Nitrogen Tetroxide. These are chemicals that ignite spontaneously the second they touch each other. No spark plugs. No starter motor. Just open the valves and boom, you have thrust.

It produced about 20,500 pounds of thrust. That doesn't sound like much compared to the Saturn V, but in the vacuum of space, it was enough to change their trajectory or blast them out of lunar orbit. Every time that engine fired, the crew held their breath. If it failed to ignite behind the moon during the "Teague" (Trans-Earth Injection), they were never coming back.

How They Handled the Heat

Reentry is the most violent part of any spaceflight. The command and service module would hit the Earth's atmosphere at roughly 25,000 miles per hour. That’s Mach 32.

The bottom of the Command Module was covered in an ablative heat shield made of epoxy resin. As it hit the air, the shield would literally char and melt away, carrying the heat with it. This is "ablative cooling."

But here’s the cool part: the CM didn't just fall like a rock.

Because the center of gravity was slightly offset, the astronauts could actually "fly" the capsule. By rotating the craft, they could use the lift generated by the blunt shape to skip off the atmosphere like a stone on a pond or dive deeper to shed speed. This allowed them to steer toward the recovery ship. If they didn't have that control, they might land in the middle of the Pacific with no one around for a thousand miles.

📖 Related: Wolf Creek Generating Station: How This Kansas Nuclear Giant Actually Works

The Service Module's Secret Role

People forget the Service Module also acted as a shield. It took the brunt of micrometeoroid impacts and solar radiation while the crew was en route to the moon. It also housed the fuel cells.

These fuel cells were genius. They combined hydrogen and oxygen to create electricity. And the byproduct? Pure water. The crew literally drank the "exhaust" of their power system. It was a closed-loop dream, though it did make the water a bit bubbly, which apparently gave the astronauts some pretty legendary indigestion.

Why We Don't Build Them Like This Anymore (Or Do We?)

Look at the Orion spacecraft or SpaceX’s Dragon. They look suspiciously like the Apollo command and service module.

The physics haven't changed. The "blunt body" shape is still the most efficient way to bleed off speed during reentry without burning up. We use better computers now, and we use solar panels instead of just fuel cells, but the DNA of the CSM is in everything we send to deep space.

The biggest difference today is the electronics. The Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) was a marvel of rope memory—literally wires woven through magnetic cores by hand. Today, your phone has millions of times more memory. But that old AGC never crashed. It was rugged, predictable, and it got them home.

The Apollo 13 Miracle

You can't discuss the CSM without mentioning the one time it failed. An oxygen tank in the Service Module exploded on the way to the moon. It ripped the side panel off and drained the power.

The CSM became a dead hunk of metal.

The only reason Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise survived was because they used the Lunar Module as a lifeboat. But the LM didn't have a heat shield. For the final leg of the journey, they had to power the Command Module back up. They had to pray the electronics hadn't frozen and that the heat shield hadn't been cracked by the explosion. It worked. That speaks to the "over-engineering" of the 1960s. Everything was built with a safety margin that would make a modern bean-counter cry.

Moving Forward: Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you're looking to dive deeper into how these machines actually functioned, don't just watch the movies. The real gold is in the technical documentation.

- Study the Apollo Operations Handbook: You can find the original PDFs online. It’s the actual manual the astronauts used. Reading the "Emergency Procedures" section gives you a chilling perspective on how many things could go wrong.

- Visit the Real Hardware: If you're in the US, go to the Smithsonian in D.C. to see the Columbia (Apollo 11) or the Kennedy Space Center to see the unused Apollo hardware. Seeing the scale in person—the tiny size of the crew cabin versus the massive engine bell—changes your perspective.

- Track the Orion Missions: NASA’s Artemis program uses the Orion capsule, which is essentially the spiritual successor to the CSM. Comparing the two shows you exactly where we’ve improved (thermal protection, avionics) and where the laws of physics have kept us in the same "cone-shaped" box.

- Analyze the Flight Journals: The Apollo Flight Journal, curated by David Woods, provides a minute-by-minute transcript of everything said in the CSM. It’s the best way to understand the "man-machine" interface that made these missions successful.

The command and service module was a bridge. It took us from a world that had never left its own backyard to a world that had walked on another celestial body. It was cramped, dangerous, and incredibly complex, but it remains the benchmark for what humans can achieve when they stop worrying about the cost and start worrying about the physics.