You’ve seen the screenshots. Maybe you thought the art looked a little... well, ugly. Or maybe you heard it’s just another "Obra Dinn clone." Honestly, if that’s where you stopped, you’ve missed out on the most inventive mystery game of the last decade. The Case of the Golden Idol isn't just about pointing and clicking on gruesome 18th-century corpses. It’s a logic engine that makes you feel like a genius by refusing to hold your hand.

Most people think detective games are about finding the "thing" that triggers the next cutscene. This game is the opposite. It gives you all the pieces up front and then walks away. It's basically a series of interactive dioramas where time is frozen at the exact moment of a murder. Your job? Figure out the who, how, and why using a "Thinking Panel" that looks like a high-stakes version of Mad Libs.

👉 See also: Kingdom Come Deliverance 2 All's Fair: Why Henry's New Morality System Changes Everything

Why the Case of the Golden Idol is Actually a Masterpiece

The magic happens when you realize the game doesn't just want you to identify a killer. It wants you to understand a forty-year conspiracy involving a weird, supernatural artifact. You aren't just looking for bloodstains; you're looking for dinner seating charts, political pamphlets, and receipts for stomach tonics.

Developed by Latvian brothers Ernests and Andrejs Kļaviņš (Color Gray Games), the game leans into a "disembodied" investigation style. You aren't a character in the world. You’re a ghost, an observer, a fly on the wall that can rifle through pockets without being noticed. This removes the "logic gap" found in many adventure games where you know the answer but can't get your character to say it. Here, if you know it, you just slot the words into the scroll.

The "Obra Dinn" Comparison

People love to compare this to Lucas Pope’s Return of the Obra Dinn. It makes sense—both use frozen moments and deductive reasoning. But where Obra Dinn focuses on identity and cause of death, The Case of the Golden Idol forces you to understand motivation. You’ll spend ten minutes trying to figure out why a guy in a powdered wig is hiding a key in a potted plant, only to realize it connects to a case you solved three chapters ago.

The Weird, Grotesque Beauty of 18th-Century Crime

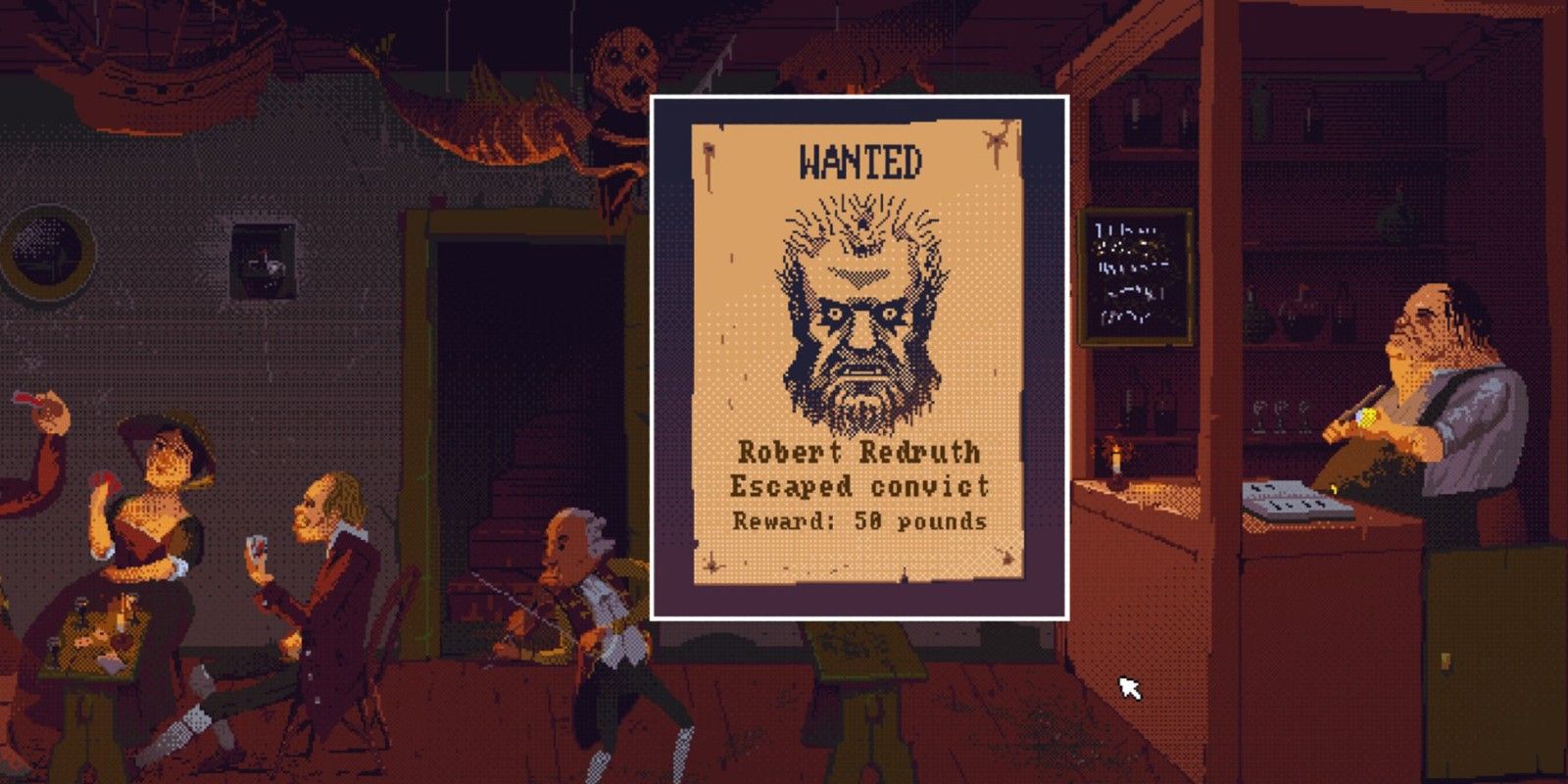

Let’s talk about the art. It’s polarizing. Some call it "grotesque," others say "striking." It’s a 1990s-inspired pixel art style that feels intentionally "off." The characters have massive noses, double chins, and bulging eyes.

But this isn't just an aesthetic choice. It’s functional. The exaggerated features make characters instantly recognizable across decades. When you see a specific birthmark or a peculiar hat in 1742, and then see it again in 1775, the game doesn't tell you "Hey, look, it's that guy!" You have to notice it.

Breaking Down the Complexity

Each case is a step up. You start in a simple cabin and end up in sprawling country estates and secret society headquarters.

👉 See also: Perk Latas de Call of Duty: Why We Keep Buying Real-Life Juggernog

- The Exploration Phase: You click on everything. You collect "keywords." Names, verbs, places.

- The Thinking Phase: You drag those keywords into scrolls.

- The "Two Words Off" Mechanic: This is a lifesaver. If you’re almost right, the game tells you. It prevents you from getting stuck on a tiny technicality while still making you do the heavy lifting.

Misconceptions About the Difficulty

A lot of players get intimidated by the later chapters. Honestly, the game is fair. If you're stuck, it’s usually because you’ve made an assumption that isn't true. Maybe you assumed the guy holding the knife is the killer. In this game? He’s probably the victim’s best friend who just arrived.

The DLCs—The Spider of Lanka and The Lemurian Vampire—actually crank the difficulty up even higher. If the base game is a warm-up, the DLC is a marathon. They introduce new rules, like life-draining mechanics and ancient rituals, that require you to learn an entirely new logic system before you can even begin the murder investigation.

Is the Sequel Actually Better?

With the release of The Rise of the Golden Idol in late 2024, the series jumped into the 1970s. The neon lights and polyester suits replaced the powdered wigs. While the sequel is fantastic, the original The Case of the Golden Idol remains the "purist" experience. The 18th-century setting feels more claustrophobic and personal. The way the Cloudsley family saga unfolds is tight, mean, and incredibly rewarding.

What You Should Do Next

If you haven't played it yet, don't look up a walkthrough. Seriously. The entire value of the game is the "Aha!" moment. Once you know the solution, you can never "un-know" it, and the magic is gone.

- Play the Demo: It covers the first few cases and gives you a perfect feel for the loop.

- Take Notes (Real Ones): While the game has a built-in log, sometimes sketching out a timeline or a family tree on a physical piece of paper helps the brain click.

- Watch the Details: Check the pockets. Read the letters. Look at the paintings on the walls. Everything is there for a reason.

- Don't Brute Force: It’s tempting to just swap words until the "Solved" notification pops up. Don't. You’ll rob yourself of the satisfaction of actually understanding the conspiracy.

The story of the Cloudsleys, the Brotherhood of Masks, and that cursed hunk of gold is one of the best-written narratives in indie gaming. It’s messy, it’s dark, and it’s occasionally hilarious. Stop overthinking the art style and start overthinking the crimes.

Pro Tip: If you're playing on PC, use the "Highlight All" button sparingly. It's better to find the clues naturally by looking at the scene as a whole rather than just hunting for pixels to click.

Finish the base game before touching the DLC. The difficulty curve is designed to be climbed, not jumped. Once you wrap up the final case, you’ll see how all those seemingly random deaths were actually part of a single, horrifying machine. That realization is why people are still talking about this game years later.