Alexander Graham Bell was basically a guy obsessed with sound. That’s the simplest way to put it. People think of the first telephone ever made as some grand, polished invention that popped out of a laboratory ready to change the world, but honestly? It was a mess. It was a wooden stand, a funnel, some acid, and a lot of copper wire that barely worked. If you saw it today, you’d probably think it was a broken science project from a middle school basement.

Bell wasn’t even trying to build a phone at first. He was trying to fix the telegraph. The telegraph was the "internet" of the 1870s, but it had a massive problem: it could only send one message at a time over a single wire. Bell, along with a lot of other inventors like Elisha Gray, was racing to create a "harmonic telegraph" that could send multiple messages using different musical pitches.

Then things got weird.

Bell realized that if you could send multiple tones, you could maybe—just maybe—send the complex vibrations of the human voice. This wasn't a "eureka" moment that happened overnight. It was months of frustration in a hot Boston attic.

The Day the First Telephone Ever Made Actually Spoke

March 10, 1876. That’s the date everyone cites.

Thomas Watson, Bell’s assistant, was in another room. Bell was hunched over his weird contraption, which used a liquid transmitter. Basically, there was a cup of water and sulfuric acid. A needle attached to a parchment diaphragm vibrated when Bell spoke, changing the electrical resistance in the liquid. It was a "liquid transmitter," and it was finicky as hell.

"Mr. Watson—come here—I want to see you."

Those were the words. No grand speech about humanity. Just a guy asking his assistant for help because he’d reportedly spilled some acid on his clothes, though some historians argue the "spill" story might be a bit of a myth added later for flavor. What matters is that Watson heard him. The voice was metallic, scratchy, and faint, but it was distinct.

It worked.

The first telephone ever made had officially transmitted intelligible speech. But here’s the kicker: the patent was actually filed before the machine even worked perfectly. Bell’s patent, U.S. Patent No. 174,465, is often called the most valuable patent in history, but at the time, it was just a piece of paper describing a theory.

Why Elisha Gray Almost Won

History is written by the winners, but Elisha Gray was literally hours away from being the guy we talk about. Gray arrived at the patent office on the exact same day as Bell’s lawyer—February 14, 1874.

Imagine that.

Valentine’s Day. Two guys show up with designs for a device that sends voice over wires. There is still a massive amount of controversy among tech historians like Seth Shulman, who wrote The Telephone Gambit, suggesting that Bell might have gotten a "sneak peek" at Gray’s caveat (a notice of intent to file a patent). Gray’s design specifically used a liquid transmitter—the very thing Bell used for his successful March 10th test. Bell’s earlier designs were slightly different.

Did Bell "borrow" the idea? It’s a messy debate. But the patent office gave Bell the priority, and that’s why his name is on the company that eventually became AT&T.

How the First Telephone Actually Worked (Technically Speaking)

If you stripped down the first telephone ever made, you wouldn't find a keypad or a battery.

The 1876 model was a "vibrating reed" system initially, which transitioned into the liquid transmitter and eventually a magnetic induction setup. Basically, when you speak into the funnel, the sound waves hit a thin membrane. On the other side of that membrane is a needle or a piece of iron. As the membrane vibrates, it moves the iron near a magnet wrapped in wire.

This movement creates a tiny, tiny amount of electricity.

That current travels down the wire to the receiving end, where the process happens in reverse. An electromagnet vibrates a different membrane, which moves the air, which hits your ear.

It’s elegant. Simple. And at the time, people thought it was a magic trick.

- The Diaphragm: A thin sheet that catches sound waves.

- The Medium: In the very first version, it was the acid-water mix. Later, it was just magnetic induction.

- The Receiver: Usually looked like a wooden funnel you had to press hard against your ear.

You couldn't talk and listen at the same time very easily. You had one hole. You’d speak into it, then quickly move the device to your ear to hear the reply. It was awkward. People shouted. They didn't know how loud they needed to be.

The Public Thought it was a Toy

Western Union, the giant of communication back then, basically laughed at Bell. There’s a famous (though debated) internal memo from 1876 that supposedly said the telephone had "too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication."

They thought it was a novelty. Who would want to talk to someone when you could send a clear, printed telegram?

They were wrong.

By the time the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition rolled around in 1876, Bell got his chance to show it off. Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil was there. He picked up the receiver, listened, and reportedly dropped it, shouting, "My God, it talks!"

That was the turning point. When royalty gets shocked, the press pays attention.

Evolution After 1876

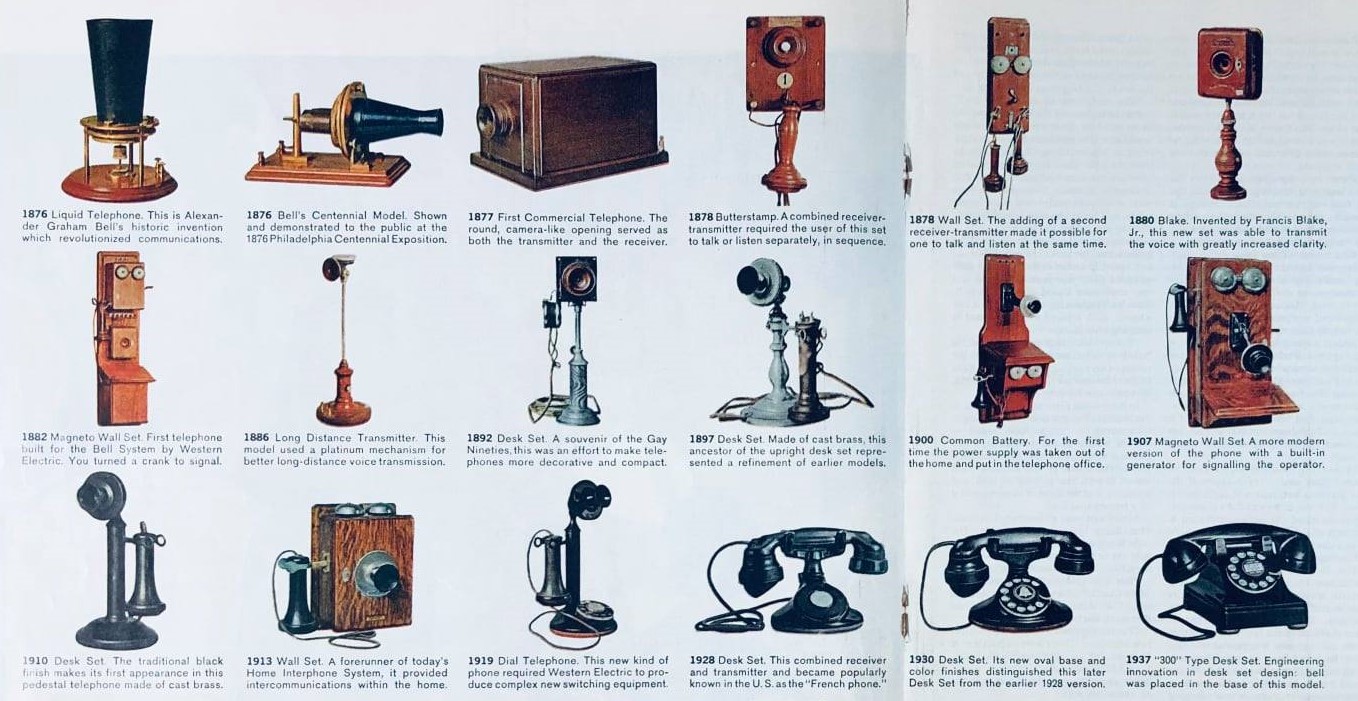

The first telephone ever made didn't stay the same for long. By 1877, the "box telephone" appeared. It looked like a camera on a tripod. Then came the "gallows" phone.

Then came the money.

Bell formed the Bell Telephone Company in 1877. Within a year, the first telephone exchange opened in New Haven, Connecticut. You didn't call people directly yet. You called an operator. Usually, these were teenage boys, but they were too rude and kept swearing at the customers, so the company started hiring women instead.

Common Myths About the First Phone

We need to clear some things up because history gets blurry.

First off, Antonio Meucci. Many people, especially in Italy, argue that Meucci invented the phone in 1871. He actually filed a caveat for a "teletrofono." He was poor, couldn't afford the $10 fee to renew his caveat, and his models were allegedly lost in a lab. In 2002, the U.S. House of Representatives even passed a resolution acknowledging Meucci’s work. So, while Bell has the patent, he wasn't the only genius in the room.

Second, the "Watson" quote. While it's the most famous first phrase, Bell’s notebooks show he was experimenting with other sounds for weeks. The March 10th success was just the first time the sentence was clear.

Third, the ringer. The first telephone ever made didn't ring. You just had to hope someone was listening on the other end, or you’d tap on the diaphragm to make a clicking sound.

Actionable Insights for Tech History Buffs

If you’re interested in the roots of communication, you shouldn't just read about it.

👉 See also: Getting the Picture of Ionic Bonding Right: Why Most Textbooks Overlook the Real Magic

- Visit the Smithsonian: The National Museum of American History in D.C. actually holds Bell’s original experimental equipment. Seeing the scale of the copper coils in person is wild.

- Check the Patent Records: You can look up Patent No. 174,465 online. Reading the actual language Bell used to describe "undulating currents" shows how he was thinking about physics, not just gadgets.

- Compare to Modern VoIP: Think about how far we've come. The first phone used analog waves in liquid; your phone now turns your voice into binary code ($1$s and $0$s), slices it into packets, and sends it via light through fiber-optic cables.

- Recognize the "Multiple Discovery" Theory: The telephone is a prime example of "Multiple Discovery." Usually, when an idea's time has come, several people hit on it at once. Don't just credit one "lone genius."

The first telephone ever made was the beginning of the end of distance. Before it, your voice could only go as far as you could yell. After it, the world started shrinking. It took about 15 years for phones to become a "must-have" for businesses and another 50 for them to be in every home, but that rickety wooden stand in 1876 started the whole thing.

The next time you pull a glass slab out of your pocket to send a text, remember Bell and Watson in a sweaty attic, spilling acid and shouting into a funnel just to see if a wire could carry a whisper.