History is messy. Usually, the stuff we learn in school gets boiled down to a single sentence or a catchy name, but the reality on the ground is way more complicated and, honestly, a lot darker. When people talk about the Great Potato Famine Ireland experienced between 1845 and 1852, they often picture a simple natural disaster. A fungus shows up, the potatoes die, and people go hungry. But that’s only half the story. If it were just about a plant disease, a million people wouldn't have died while ships full of food were leaving Irish ports every single day.

It was a total system failure.

You’ve got to understand the sheer scale of the dependency. By the 1840s, almost half the Irish population—mostly the rural poor—lived almost entirely on the "Lumper" potato. It was a high-yield, nutrient-dense crop that grew well in crappy soil. Then, Phytophthora infestans arrived.

What Really Happened During the Great Potato Famine Ireland

The blight didn't just make the potatoes taste bad. It turned them into black, mushy, foul-smelling slime overnight. Imagine waking up, counting on your winter food supply, and finding nothing but rot. In 1845, a third of the crop failed. By 1846, it was a total wipeout.

People were desperate.

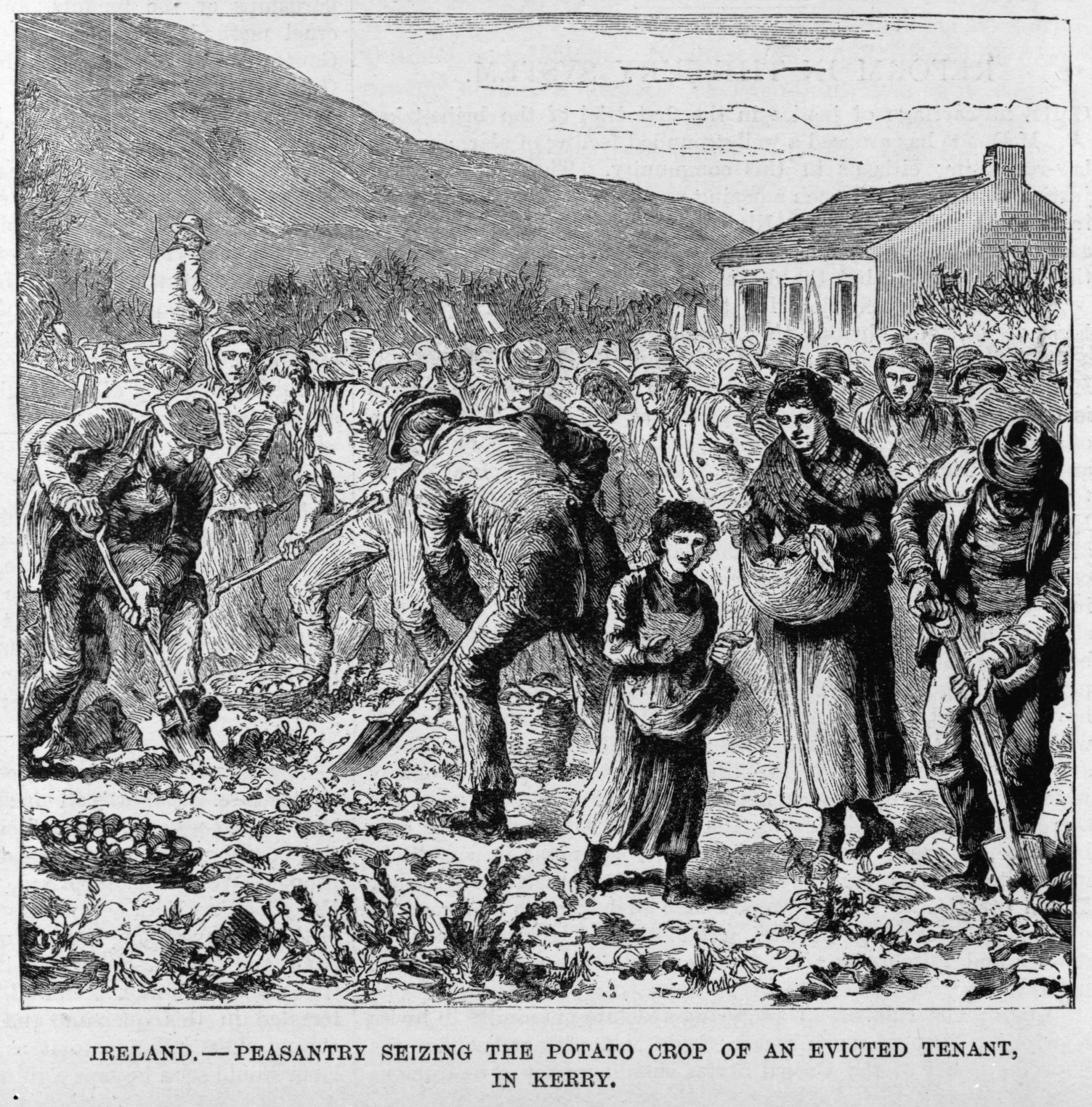

But here is where the history gets uncomfortable. Ireland was part of the United Kingdom at the time, the richest empire on the planet. While the census was dropping by millions due to death and emigration, Ireland was actually exporting massive amounts of grain, cattle, and dairy to England. Historians like Cecil Woodham-Smith and modern scholars like Christine Kinealy have pointed out that the British government’s "laissez-faire" economic policy basically meant they didn't want to interfere with the "free market."

They let people starve to protect trade.

Charles Trevelyan, the guy in charge of relief, actually believed the famine was a "mechanism" to reduce the population and teach the Irish a lesson about self-reliance. It’s hard to wrap your head around that kind of coldness, but that was the prevailing thought in Westminster. They set up "Workhouses" where families were split up—men in one wing, women in another, kids somewhere else—just to get a bowl of watery maize porridge called "Peel’s Brimstone."

It was miserable. Truly.

The Disease Nobody Talks About

Most people assume everyone died of starvation. Actually, it was mostly disease. When you’re starving, your immune system just quits. People crowded into workhouses or huddled together in "famine pits" (mass graves), which became breeding grounds for typhus and relapsing fever. They called it "Black Fever."

Then came the "Roads to Nowhere."

To get "relief" money, the government made starving men break rocks to build roads that led absolutely nowhere. You can still see some of these "famine roads" today in places like Connemara or the Burren. They are haunting. Men were literally working themselves to death for pennies that couldn't even buy enough grain to replace the calories they burned breaking the rocks. It was a cruel, circular logic.

The Mass Exodus and the Coffin Ships

If you didn't die and you didn't end up in a workhouse, you left. This is why there are more people of Irish descent in the U.S., Canada, and Australia than there are in Ireland today.

📖 Related: The Tenerife Airport Disaster: Why the KLM Pan Am Collision Still Haunts Aviation

- They boarded "Coffin Ships."

- These were often old cargo vessels not meant for passengers.

- Mortality rates on the Atlantic crossing were sometimes 20% or higher.

- Grosse Île in Quebec became a massive quarantine station for the dying.

Imagine being so desperate that you’d get on a leaking boat with hundreds of sick strangers, knowing you might never see land again. That was the reality for millions.

Lasting Scars on the Irish Landscape

If you travel through the West of Ireland today—places like Mayo or Skibbereen—you’ll see "lazy beds." They look like corrugated ridges on the hillsides. These are the old potato furrows, frozen in time because no one ever went back to farm them. The families who worked them died or fled.

The Great Potato Famine Ireland changed the language, too. Irish (Gaeilge) was the primary language of the rural poor—the ones hardest hit. When they died or moved to English-speaking cities in America, the language took a hit it still hasn't fully recovered from.

Modern Perspectives and E-E-A-T

Today, researchers look at the famine through the lens of food security and colonial mismanagement. It wasn't just a "famine" in the sense of a lack of food; it was a "famine" in the sense of a lack of access to food. This is a distinction that experts like Cormac Ó Gráda emphasize in their work. Ireland had food. It just didn't have food for the Irish.

What You Can Do to Honor the History

If you’re interested in this period, don’t just read a Wikipedia page. There are ways to actually engage with this history that provide a much deeper understanding of what happened.

- Visit the National Famine Museum at Strokestown Park: This is essential. It’s built on the site of a former estate and holds the actual papers of the landlord who was assassinated during the famine. It shows the perspective of both the starving tenants and the struggling gentry.

- Support Modern Food Security: The best way to honor the victims of the 1840s is to help those facing similar "man-made" famines today. Organizations like Concern Worldwide (which has Irish roots) work on global hunger issues that mirror the systemic problems of the 1840s.

- Research Your Ancestry: If you have Irish roots, use databases like the National Archives of Ireland to look at the Tithe Applotment Books. You can see the names of the people who lived on those "lazy beds" before the blight hit.

- Walk a Famine Trail: The National Famine Way is a 165km walking trail that follows the path of 1,490 emigrants who walked from Roscommon to Dublin to catch a ship. It’s a powerful, sobering experience.

The tragedy wasn't inevitable. It was the result of a specific set of political choices. Understanding that helps us realize that today’s global food issues are often about policy, not just rain or soil. History isn't just in the past; it's a warning.

Next Steps for Deeper Insight:

To get a truly unfiltered look at the era, look for the "Annals of the Famine in Ireland" by Asenath Nicholson. She was an American woman who traveled through Ireland during the height of the crisis and recorded exactly what she saw in the cabins of the poor. Her accounts are some of the most visceral, first-hand reports available and strip away the clinical, dry language of government reports from the time.