It was supposed to be the victory lap for human engineering. On September 10, 2008, the world watched as the first beams of protons successfully circled the 27-kilometer ring under the French-Swiss border. Scientists were popping champagne. The media was obsessed with a fringe theory that the machine would create a black hole and swallow the Earth. That didn’t happen. Instead, just nine days later, a massive large hadron collider accident nearly destroyed the most expensive scientific instrument ever built.

It wasn't a black hole. It was a bad solder joint.

Imagine spending $5 billion and decades of your life building a machine that can recreate the conditions of the Big Bang, only to have it sidelined by a faulty connection smaller than a coin. That’s the reality of high-stakes physics. When things go wrong at near-absolute zero, they go wrong fast.

The Day the Magnets Quenched

Around midday on September 19, 2008, during a final series of tests before high-energy collisions were set to begin, a "quench" occurred in Sector 3-4. In the world of cryogenics, a quench is basically a nightmare. The LHC uses superconducting magnets to steer protons. These magnets only work because they are cooled by liquid helium to roughly $1.9$ Kelvin ($-271.3$°C). That is colder than outer space.

At these temperatures, electricity flows without resistance. But if a tiny part of the wire warms up—even by a fraction of a degree—it loses superconductivity. Resistance returns. The energy stored in the magnet has nowhere to go, so it turns into heat.

The heat was intense.

In Sector 3-4, a single electrical interconnect between two magnets had too much resistance. It was likely a "bad solder job," though calling it that feels a bit reductive given the scale. When $8,700$ amperes of current hit that weak spot, it didn't just melt; it vaporized. This created an electrical arc that punctured the vacuum enclosure.

Helium and Force

Think about the physics here. Liquid helium expands massively when it turns into gas. About six tons of it leaked into the tunnel. The pressure was so immense that it actually buckled the steel supports and ripped several massive, 35-ton magnets off their floor moorings.

It was a mess.

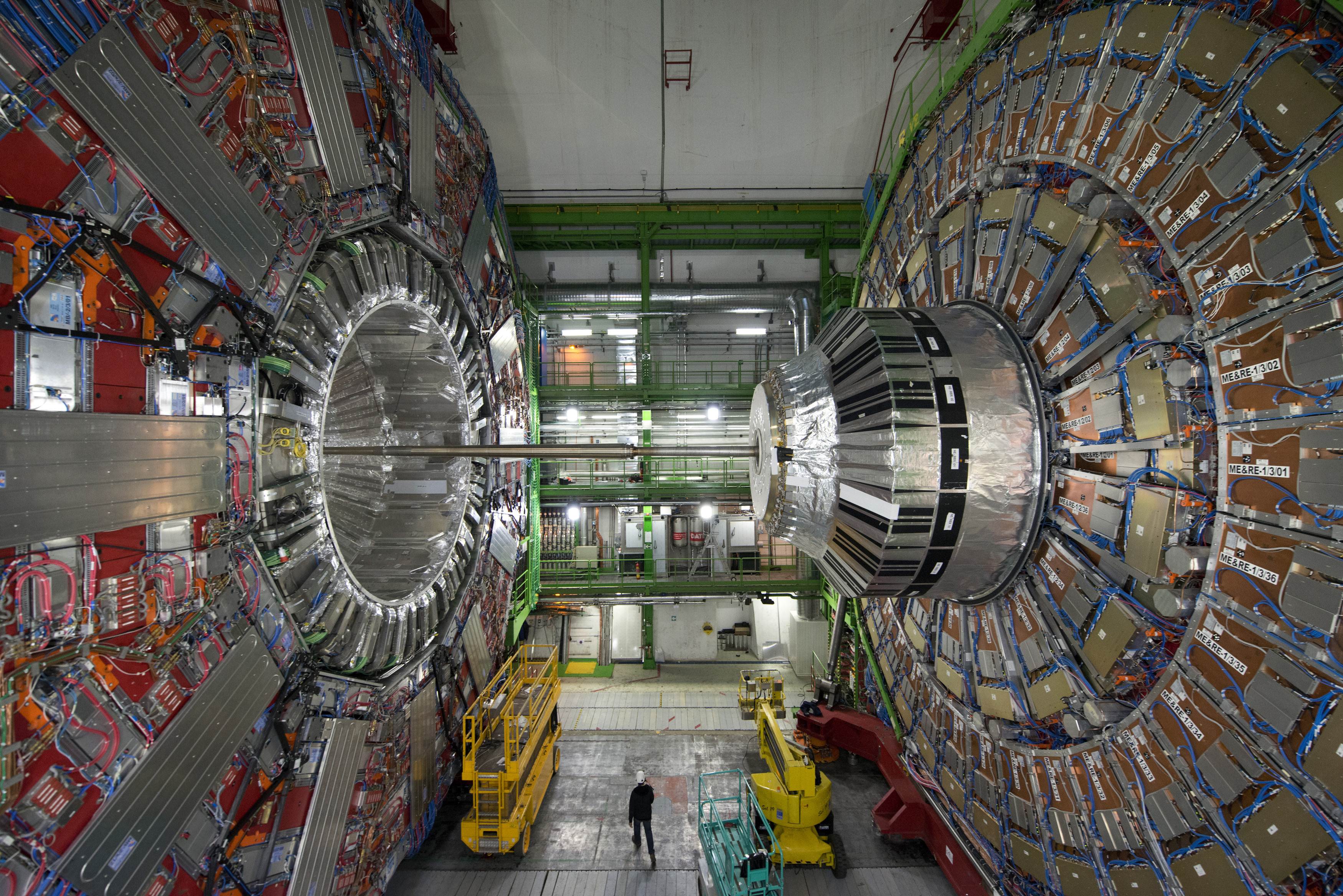

One of the most striking things about the large hadron collider accident was the physical displacement. These magnets are not light. They are the size of buses. Seeing them shoved inches out of alignment by expanding gas showed the raw, terrifying power stored within the machine. CERN engineers, including Lyn Evans, who was the project leader at the time, had to face the reality that their machine was broken before it even really started.

Why We Didn't Hear More About It

At the time, the public was mostly worried about the "End of the World" scenarios. When the accident happened, CERN was surprisingly transparent, but the technical details were so dense that the general public mostly just heard "the machine is off for repairs."

Inside the lab, the mood was different.

There was genuine fear about the structural integrity of the entire 17-mile loop. If one joint failed, how many others were ticking time bombs? This wasn't just a quick fix. They had to warm up the entire sector—a process that takes weeks because you can't just flip a heater on for something that cold—then open the tubes, replace the magnets, and clean out the soot.

Yes, soot.

The electrical arc had left carbon deposits inside the ultra-pure beam pipes. If even a tiny speck of dust remains in the path of a proton beam moving at $99.999999%$ the speed of light, it’s like a car hitting a brick wall. The "vacuum" inside the LHC has to be emptier than the space between planets.

The Real Cost of the Failure

- Financial hit: The repairs and the new safety systems cost roughly 40 million Swiss Francs (about $45 million USD).

- Time lost: The collider was offline for over a year. It didn't see beams again until late 2009.

- Reputational risk: Skeptics and politicians started asking if the project was "too big to fail" or just "too big to work."

Honestly, the delay might have been a blessing in disguise. It forced the team to install thousands of new sensors. They developed the "quench protection system" (QPS), which is now so sensitive it can detect the tiniest voltage drop and dump the energy safely before an arc starts. They basically turned the LHC into a "smart" machine during that downtime.

What People Get Wrong About the Risk

People often ask: "Could it happen again?"

The short answer is no, not like that. The 2008 large hadron collider accident happened because they didn't know what they didn't know. They assumed the soldering was uniform. Now, every single one of the 10,000+ interconnects is monitored.

Also, the "black hole" thing? Still not a concern. Even if the LHC produced a microscopic black hole (which it hasn't), it would evaporate via Hawking Radiation in a fraction of a second. The real danger at CERN is always the plumbing. It’s the high-pressure gas, the high-voltage electricity, and the extreme cold. It’s more "industrial accident" than "sci-fi catastrophe."

The 2015 "Weasel" Incident

If you want to talk about accidents, we have to mention the weasel. In 2016 (and a similar incident involving a bird and a piece of baguette earlier), a small beech marten—a relative of the weasel—gnawed through a 66-kilovolt transformer cable. It caused a power outage that shut down the whole facility.

The marten didn't survive. The LHC did.

👉 See also: Funny Status for Discord: Why Most People Are Still Using Mid Jokes

It goes to show that while we're looking for the Higgs Boson and Dark Matter, the biggest threats are often incredibly mundane. Whether it's a poorly soldered wire or a hungry rodent, the "complex" failures are usually just a series of simple things going wrong at the same time.

Lessons Learned from the Breakdown

CERN’s recovery was actually a masterclass in crisis management. They didn't hide the flaw. They published reports. They invited external experts to audit the repairs. Because of that transparency, the scientific community stayed on their side. When the LHC finally ramped up to full power and discovered the Higgs Boson in 2012, the 2008 disaster felt like a distant memory.

But it changed how we build big science. The upcoming High-Luminosity LHC upgrade and the proposed Future Circular Collider (FCC) are being designed with "failure modes" as the primary focus. We learned that you can't just build for the success of the experiment; you have to build for the violence of the failure.

Taking Action: How to Follow LHC Progress

If you're interested in the "health" of the machine today, you don't have to wait for a news report. CERN actually provides live dashboards of the beam status.

- Check the Vistars: CERN "Vistars" are public-facing monitors that show exactly what the beams are doing in real-time. If the screen is green, things are good. If it’s red, they’re usually "dumping" the beam for maintenance.

- Read the Incident Reports: For the truly nerdy, CERN’s document server (CDS) hosts the full technical analysis of the 2008 incident. It’s a fascinating look at forensic engineering.

- Monitor the Upgrades: The LHC is currently in a phase of increasing "luminosity" (collision density). This means more data, but also more strain on the magnets. Watching the "Long Shutdown" schedules tells you when the most critical maintenance is happening.

The 2008 large hadron collider accident wasn't the end of the world, but it was a sobering reminder that even our most advanced technology is still subject to the basic laws of heat, pressure, and human error. We are poking the universe with a very big, very cold stick. Sometimes, the stick breaks.