Space is big. You know that. But humans are actually pretty terrible at visualizing just how much the "stuff" out there differs in scale. When you look at a list of solar system objects by size, it’s not just a neat ranking of balls of rock and gas. It is a story of gravity’s winners and losers.

Most of us grew up with those classroom posters where the planets look like a set of marbles lined up on a desk. Jupiter is a bit bigger than Earth, and Saturn has some rings, right? Wrong. The reality is much more violent and lopsided. If you took all the planets, moons, asteroids, and comets and shoved them into a cosmic blender, the Sun would still account for roughly 99.8% of the total mass. We are living in the leftovers of a much larger construction project.

The Absolute Heavyweights

Let's start at the top. The Sun is the undisputed king. It’s so massive that its diameter is about 109 times that of Earth. To put that in perspective, you could fit about 1.3 million Earths inside it. It’s a G-type main-sequence star, and frankly, everything else on this list is just a rounding error compared to it.

Jupiter: The Failed Star?

Jupiter is the first thing people look for on a list of solar system objects by size after the Sun. It’s a monster. With a mean radius of about 69,911 kilometers, it’s more than twice as massive as all the other planets combined. Honestly, if it had been about 80 times more massive, it might have started nuclear fusion itself, turning our system into a binary star setup.

Jupiter isn't just big; it's a bully. Its gravity is so intense that it likely prevented a planet from forming between it and Mars, leaving us with the Asteroid Belt instead. It’s mostly hydrogen and helium, a gas giant that doesn't even have a solid surface you could stand on. You’d just sink into the metallic hydrogen layers until the pressure crushed you into a soup.

Saturn: The Ringed Giant

Saturn follows closely behind. It’s about 9.5 times the size of Earth in terms of radius. While it’s famous for those rings—which are mostly water ice and rock—Saturn is actually the least dense planet. If you had a bathtub big enough, Saturn would float. This is a weird quirk of planetary science; size doesn't always equal density. It’s a massive, puffed-up ball of gas that still holds onto dozens of moons, including Titan, which is actually larger than the planet Mercury.

The Ice Giants and the "Small" Big Guys

Moving further out, we hit Uranus and Neptune. We call these "Ice Giants." Why? Because while they have hydrogen and helium, they also have a higher proportion of "ices" like water, ammonia, and methane.

- Uranus: Roughly 4 times the diameter of Earth. It’s the weirdo that rotates on its side.

- Neptune: Slightly smaller than Uranus in diameter but actually more massive. Gravity has compressed its guts more tightly.

It’s easy to group these two together, but Neptune's winds are some of the fastest in the solar system, topping out at 2,100 kilometers per hour. Think about that. A storm on a planet four times the size of ours moving faster than a fighter jet.

Where Earth Fits In

We like to think we're a big deal. We aren't. Earth is the largest of the terrestrial (rocky) planets, but in the grand list of solar system objects by size, we’re basically a pebble.

- Earth (6,371 km radius)

- Venus (6,052 km radius - Earth’s "twin" but a hellish one)

- Mars (3,390 km radius - roughly half the size of Earth)

- Mercury (2,440 km radius - barely bigger than our Moon)

Venus is often called Earth's sister because the size difference is negligible. But the atmosphere? Totally different. Venus has a runaway greenhouse effect that makes it hot enough to melt lead. Mars, on the other hand, is a bit of a disappointment in the size department. It’s small because Jupiter’s gravity stole the material it needed to grow during the early days of the solar system.

The Moon Problem: When Satellites Outshine Planets

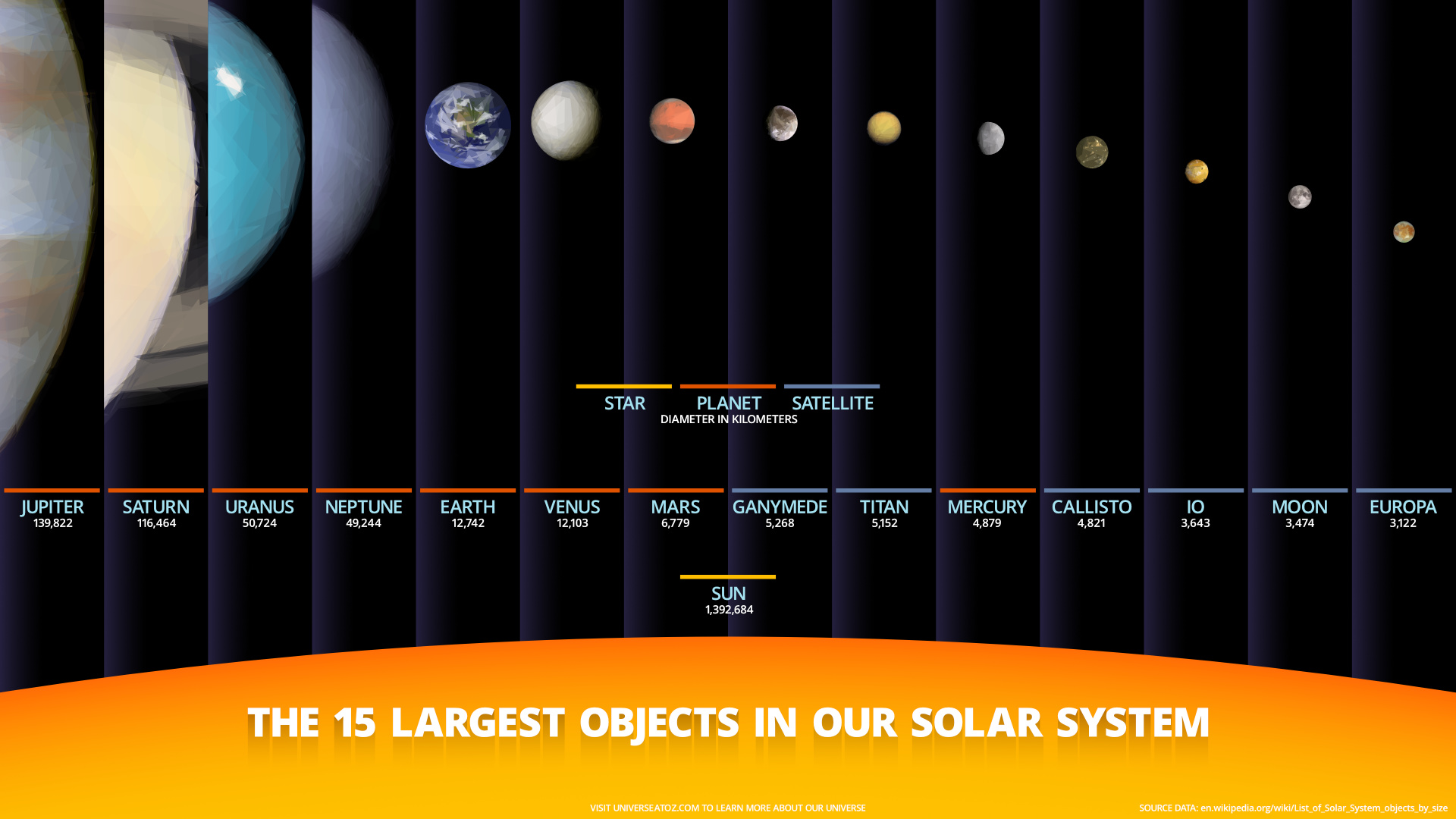

This is where the list gets interesting. If you rank every object by diameter, several moons actually beat out actual planets.

Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest moon, is bigger than the planet Mercury. So is Saturn's moon Titan. If these moons were orbiting the Sun directly instead of their parent planets, we’d almost certainly call them planets.

Then you have Callisto and Io (Jupiter) and Moon (ours), followed by Europa and Triton. Our Moon is actually the fifth-largest satellite in the solar system. For a planet as small as Earth to have a moon as big as ours is quite rare. Most moons are tiny captured asteroids. Ours was likely formed when a Mars-sized object slammed into Earth billions of years ago.

The Dwarf Planets and the Kuiper Belt

We have to talk about Pluto. It was demoted in 2006 by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), and people are still salty about it. But when you look at the list of solar system objects by size, you see why.

Pluto is tiny. It’s smaller than our Moon. It’s even smaller than Eris, another dwarf planet out in the Kuiper Belt.

- Eris: Roughly 2,326 km across.

- Pluto: Roughly 2,376 km across (Pluto is slightly larger in volume, but Eris is more massive).

- Haumea: An elongated, football-shaped world.

- Makemake: A cold, icy world with a reddish tint.

- Ceres: The king of the Asteroid Belt, but still only about 940 km across.

Ceres is a fascinating case. It’s the only dwarf planet in the inner solar system. It sits between Mars and Jupiter. It’s essentially a giant space potato that makes up a third of the total mass of the entire Asteroid Belt. Even so, it's a speck compared to the Earth.

Why Scale Matters for Discovery

In 2026, our understanding of these sizes is changing how we look for life. Smaller objects like Europa (a moon of Jupiter) or Enceladus (a moon of Saturn) are tiny compared to Earth, but they have huge subsurface oceans. Size isn't everything when it comes to geological activity.

Mike Brown, the Caltech astronomer who famously "killed" Pluto by discovering Eris, argues that the classification of these objects helps us understand the migration of the early solar system. The way these sizes are distributed tells us that the giants—Jupiter and Saturn—moved around quite a bit, tossing the smaller objects like bowling pins.

Real-World Visualization of the List

If you want to grasp this, try the "fruit scale."

If the Sun is a huge exercise ball (about 1 meter wide):

🔗 Read more: Finding a Reliable OS X 10.11 DMG Download for Older Macs

- Jupiter is a grapefruit.

- Saturn is a large orange.

- Neptune and Uranus are lemons.

- Earth and Venus are cherry tomatoes.

- Mars is a blueberry.

- Mercury and the Moon are peppercorns.

- Pluto? It’s a grain of salt.

It’s a bit humbling, isn't it?

Common Misconceptions About Size

One thing people get wrong constantly is thinking that mass and size are the same. They aren't. Saturn is huge, but it's "light." A bucket of Saturn material would weigh less than a bucket of Earth rock.

Another big one: the Asteroid Belt. Movies show it as a crowded field of rocks. In reality, there is so much space between objects that you could fly a spaceship through it without even trying to dodge. The objects are small, and the "neighborhood" is massive.

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you’re trying to memorize or teach the list of solar system objects by size, stop trying to remember the exact kilometers. It’s useless for your brain to hold onto "6,371 vs 6,052." Instead, categorize them by "cliques":

- The Big Two: Sun and Jupiter.

- The Ringed Pair: Saturn and its massive rings (and Titan).

- The Twins: Uranus and Neptune.

- The Rocky Four: Earth, Venus, Mars, Mercury.

- The Moon Kings: Ganymede, Titan, Callisto, Io.

To see these scales for yourself, use a digital orrery like the NASA Eyes on the Solar System. It’s a free tool that lets you compare the sizes of these objects in real-time.

Next time you look at the night sky, remember that the "stars" that don't twinkle are usually planets. That tiny dot of Jupiter is actually a world so large it could swallow 1,300 Earths. That perspective changes the way you look at a clear night. You aren't just looking at dots; you're looking at the winners of a 4.5 billion-year-old game of gravitational Tetris.