Charles Dickens was broke. Honestly, it’s hard to imagine the titan of Victorian literature checking his bank balance with a sense of impending doom, but in late 1843, that was the reality. His latest serialized novel, Martin Chuzzlewit, was flopping. His publishers, Chapman & Hall, were threatening to reduce his monthly pay. He had a mountain of debt, a growing family, and a serious case of writer's block. Most people know the story of Scrooge, but the backstory of The Man Who Invented Christmas book by Les Standiford is actually much more intense. It’s a story of a man backed into a corner who accidentally saved a holiday that was basically dying out in England.

Standiford’s 2008 non-fiction work, The Man Who Invented Christmas: How Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol Rescued His Career and Revived Our Holiday Spirit, isn't just a biography. It’s a look at the intersection of commerce and art. It shows how one guy, in about six weeks of frantic work, changed how the entire world views December 25th.

Why Dickens Was Desperate

Dickens wasn't always the "unassailable genius" we study in English class. He was a working writer. A gig worker, essentially. After the massive success of The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist, he had started living large. He bought a big house. He traveled. Then, the public's interest started to wane. By the time he started thinking about a Christmas story, his bank account was looking pretty grim.

💡 You might also like: Where Is The Hangover 3 Streaming Right Now? Finding the Wolfpack’s Finale

He needed a hit. He didn't just want to write a nice story; he needed to pay the mortgage.

The interesting thing Standiford points out is that Christmas in the 1840s wasn't the "holiday season" we know today. It was a minor bank holiday. Most businesses didn't even close. The old traditions of the countryside—the big feasts, the caroling, the communal joy—were being crushed by the Industrial Revolution. People were moving to cities to work 16-hour days in factories. There was no time for "mistletoe and wine." Dickens saw this decay and felt it personally.

The Creation of A Christmas Carol

When you read about the timeline in The Man Who Invented Christmas book, the speed is staggering. Dickens began writing in October 1843. He finished by the end of November. Think about that. He conceived, wrote, and oversaw the production of one of the most famous stories in human history in less time than it takes most people to pick out a new sofa.

He was obsessed. He took long walks at night through the soot-stained streets of London, sometimes covering 15 or 20 miles in a single go. He was weeping over his own characters. He was laughing out loud in his study. Standiford describes a man possessed by a vision of social justice wrapped in a ghost story.

But here is the kicker: his publishers didn't believe in it. They didn't want to take the risk. So, Dickens took the ultimate gamble. He told them he would pay for the publishing costs himself in exchange for a higher percentage of the profits. He insisted on expensive gold lettering, red cloth binding, and hand-colored illustrations by John Leech. He wanted the book to be a beautiful gift. It was a massive financial risk that almost ruined him.

What Most People Get Wrong About the "Invention"

Did Dickens literally "invent" Christmas? No. Obviously not. People had been celebrating the birth of Christ for centuries. But he invented the vibe.

Before A Christmas Carol, Christmas was a religious observance and a fading folk tradition. Dickens turned it into a secular celebration of generosity and family. He put the focus on the "spirit" of the season rather than just the liturgy. Standiford argues that Dickens created the "modern" Christmas.

- The idea of the Christmas turkey? That’s Dickens. (Most people ate goose or beef).

- The phrase "Merry Christmas"? He didn't invent it, but he popularized it to the point of it becoming a standard greeting.

- The concept of a "white Christmas"? Dickens grew up during a "Little Ice Age" where it actually snowed in London eight years in a row during his childhood. He wrote that nostalgia into the book, and we’ve been chasing that snowy aesthetic ever since, even in places where it never snows.

The Business Failure That Became a Cultural Success

You’d think that after the book sold out its first 6,000 copies in mere days, Dickens would be set for life. Nope. Because he insisted on such high production values and priced the book at only five shillings (to make it accessible), his actual profit from the first run was tiny. He was devastated. He had expected thousands of pounds and ended up with about £230.

It’s a weirdly humanizing detail. The man changed the world and still felt like he’d failed because he couldn't pay his bills.

However, the cultural impact was immediate. People started sending turkeys to the poor. Charitable giving spiked. Factory owners started closing their doors on Christmas Day because the story of Scrooge made them feel like monsters if they didn't. Standiford’s book does a great job of showing how a piece of "pop culture" can actually shift the moral compass of a nation.

The Standiford Perspective vs. The Movie

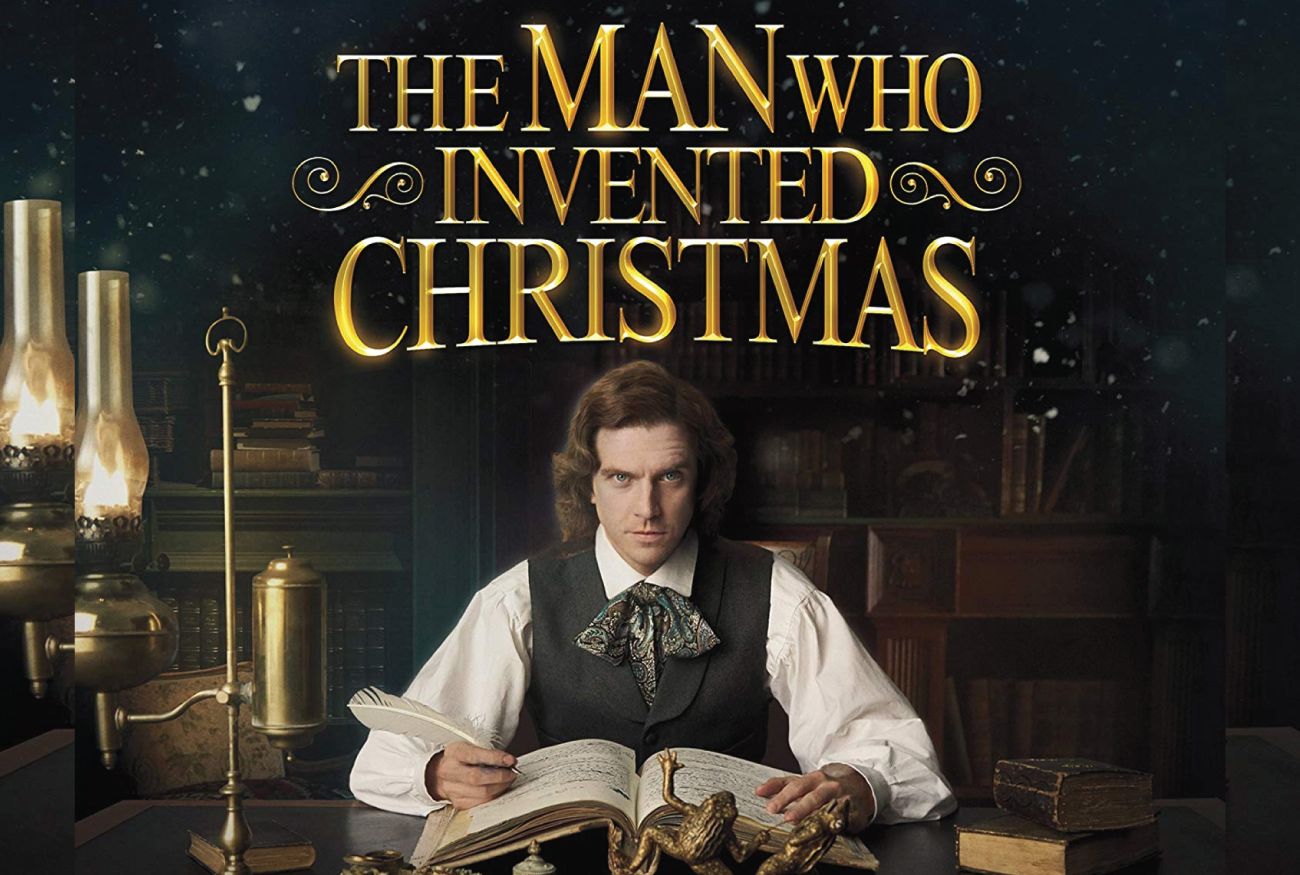

Many people found their way to The Man Who Invented Christmas book through the 2017 movie starring Dan Stevens and Christopher Plummer. While the movie is a fun, whimsical ride with ghosts popping out of the woodwork, the book is more grounded. Standiford is a master of explaining the "why." He looks at the economic conditions of the 1840s—the "Hungry Forties"—where people were literally starving in the streets while the wealthy looked the other way.

👉 See also: Why the Glendale Drive-In Theater is Still the Best Way to Watch a Movie

The book explains that A Christmas Carol was originally intended to be a political pamphlet called An Appeal to the People of England, on behalf of the Poor Man's Child. But Dickens realized that a story would have a thousand times more impact than a dry political essay. He was right.

Why This History Matters Now

We live in a world of "Christmas Creep" where decorations go up in October. It’s easy to get cynical about the commercialism. But reading Standiford’s account reminds us that the commercialism was there from the start. Dickens wanted to sell books. He wanted to make money. But he also wanted to do good.

It’s a nuanced view of history. It’s not just "man writes book, everyone is happy." It’s "man is stressed, man gambles everything, man creates masterpiece, man is still kind of broke, but the world is changed."

Practical Insights from the Story of Dickens

If you’re a creator, a business owner, or just someone who loves the holidays, there are a few things to take away from the history documented in Standiford’s work:

✨ Don't miss: Why Pursuit of Happiness Kid Cudi Still Hits So Hard 15 Years Later

- Constraints breed creativity. Dickens wrote his best work when he was under the most pressure. Sometimes a deadline is the best muse you’ll ever have.

- Visuals matter. Dickens almost went bankrupt making sure his book looked beautiful. He knew that the physical experience of the object was part of the story.

- Empathy is a powerful "brand." People didn't just buy a story about a ghost; they bought into the idea that they could be better versions of themselves.

- Bet on yourself. When the gatekeepers (the publishers) said no, Dickens used his own money. It was terrifying, but it ensured he kept control of his vision.

To really understand the holiday, you have to look at the grime of 19th-century London. You have to see the desperation. The Man Who Invented Christmas book is the best roadmap for that journey. It’s a reminder that even the most cherished traditions often start with a person just trying to figure out how to keep the lights on.

If you want to dive deeper into this specific era, your next move should be looking into the "Hungry Forties" or reading Dickens’s own letters from 1843. They are filled with the kind of raw, unfiltered anxiety that makes his eventual success feel much more earned. You can also compare Standiford’s work with Peter Ackroyd’s biography of Dickens for a more academic look at his life. Whatever you do, don't just watch the movie—the real story of the ink and the debt is much more fascinating.