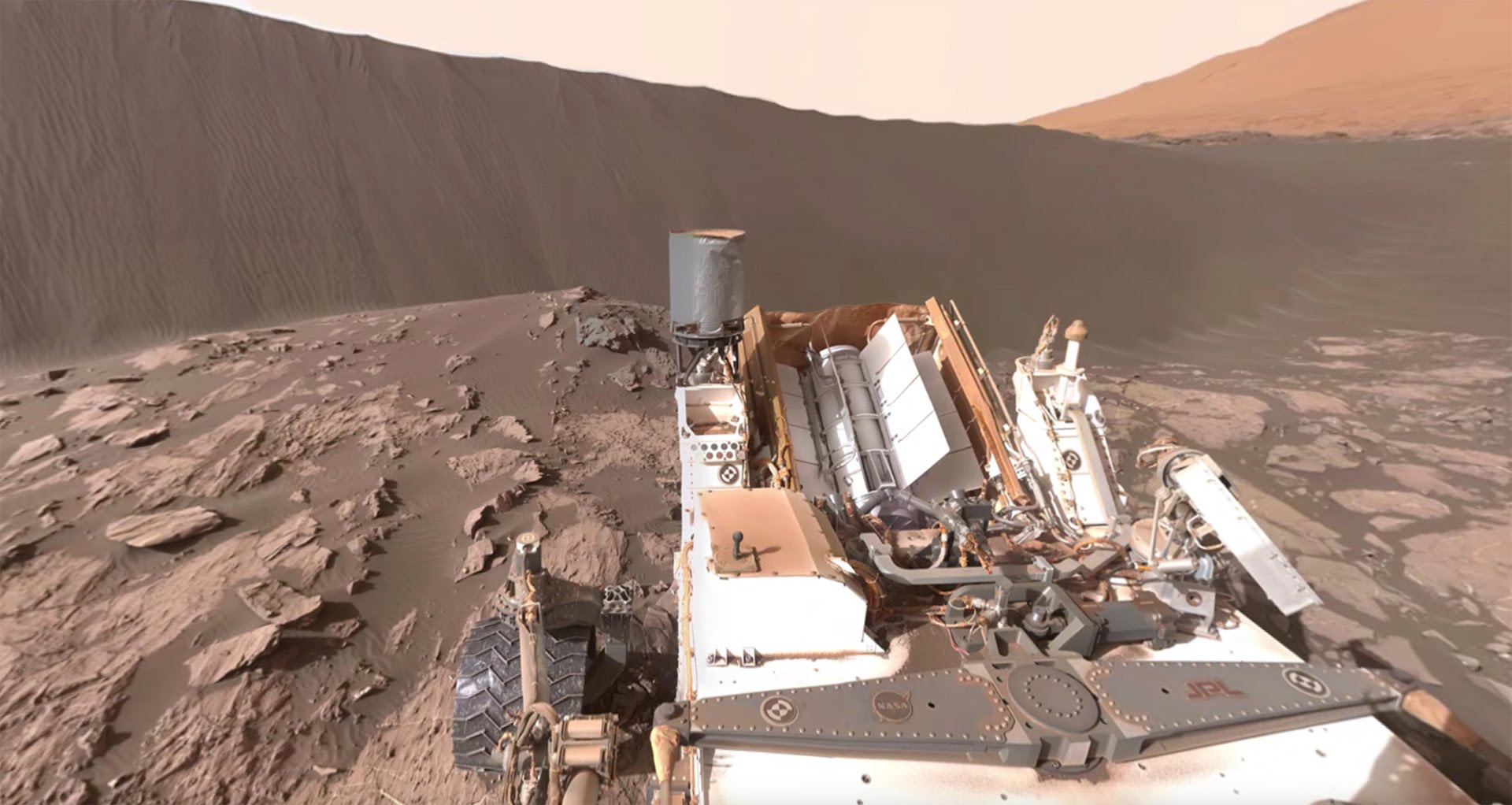

Mars isn't just a dead rock. We've known that for a long time, but sometimes a single image makes it feel visceral. Take the mars curiosity rover namib dune photo. When NASA released the high-resolution 360-degree panorama back in early 2016, it didn't just look like another planet; it looked like a high-definition vacation snap from the Namib Desert right here on Earth.

Honestly, the clarity is kind of unsettling.

The image was captured on December 18, 2015, which was Sol 1,197 of Curiosity’s mission. The rover was parked right at the base of the Bagnold Dunes, a massive band of dark sand hugging the northwestern flank of Mount Sharp. Specifically, it was staring up at the slipface of "Namib Dune," a towering wall of sand about 16 feet high.

What You're Actually Seeing in the Namib Dune Photo

The first thing people notice is the color. It’s not that "flat red" we grew up seeing in old Viking mission photos. This sand is dark. Moody. It's basaltic sand, similar to what you’d find on the volcanic beaches of Iceland or the dunes of Namibia.

NASA's Mastcam team, led by experts at Malin Space Science Systems, processed the image with a white balance adjustment. This basically means they tweaked the lighting to show what the scene would look like under Earth's sunlit sky. It’s a trick that helps geologists recognize rock textures they know from home, but for the rest of us, it just makes the Martian landscape feel incredibly familiar.

You can see the steepness of the dune—about a 28-degree slope. That’s the "angle of repose." If it were any steeper, the sand would just slide down. And it does slide. Unlike the static hills we see in many Mars photos, Namib Dune is alive. Orbital data from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) has shown these dunes migrating about three feet every Earth year.

Why This Specific Spot Mattered

Before Curiosity, we’d never actually touched an active dune on another planet.

Scientists like Bethany Ehlmann from Caltech and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory were particularly obsessed with this site. They wanted to know how the wind sorts minerals on a planet with 38% of Earth's gravity and an atmosphere only 1% as thick.

- The Scuff Test: Curiosity didn't just take pictures. It used its wheels to "scuff" into the side of the dune. This revealed the internal structure and showed that while the surface is covered in coarse grains, the inside is packed with much finer sand.

- The Mineral Hunt: Using the ChemCam laser and APXS (Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer), the team found the sand was rich in olivine and pyroxene. These are minerals that usually get chewed up by water, so their presence proves the area has been dry for a very long time.

- The Ripple Mystery: One of the biggest shocks for the science team, including Nathan Bridges from Johns Hopkins, was the size of the ripples. On Earth, we have small ripples (inches apart) and big dunes (miles apart). On Mars, there’s a "middle" size of ripple that shouldn't exist according to our physics models. Seeing them up close in the Namib Dune photo was the first "ground truth" proof that Martian wind works differently.

The Human Perspective

You've probably seen the selfie version of this too.

🔗 Read more: Productivity Tools Gsctechnologik: What Most People Get Wrong

On Sol 1,228, Curiosity used its MAHLI (Mars Hand Lens Imager) to take 57 individual photos, which were stitched together into a "selfie" at the dune. It looks like someone else is standing there holding the camera. In reality, the rover's robotic arm is just positioned in a way that it’s edited out of the final mosaic.

It’s a bit of a flex, really.

But it serves a purpose. These photos allow engineers to check the wear and tear on the rover's wheels. By the time it reached Namib, those 20-inch aluminum wheels were already showing significant holes and tears from the sharp rocks in Gale Crater. The soft sand of the Bagnold Dunes provided a much-needed break for the rover's "feet."

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you’re looking at these photos and want to dive deeper into the actual science behind them, here is how you can explore the data yourself:

- Check the Raw Feeds: You don't have to wait for NASA's "pretty" versions. The JPL Mars Science Laboratory website hosts the raw, unprocessed images from every sol of the mission. Looking at the "raw" version of the Namib Dune photo shows you the actual butterscotch-tinted sky of Mars.

- Use Google Mars: You can actually track Curiosity's exact GPS path through the Bagnold Dunes. Searching for "Gale Crater" in the Google Earth Pro (Mars mode) lets you see the topographic context of why the rover had to drive through these dunes to get up Mount Sharp.

- Study the "Windhoek" Quadrant: The area around Namib Dune was informally named the Windhoek quadrant. If you're a geology nerd, compare the Namib Dune photo to photos of the Namib Desert in Namibia. The similarities in "barchan" (crescent) dune shapes are a masterclass in how physics remains constant across the solar system, even when the atmosphere changes.

The mars curiosity rover namib dune photo remains a landmark in space exploration because it bridged the gap between "outer space" and "a place." It's not a blurry dot in a telescope. It's a real, shifting, windy desert that you could—theoretically—stand on.

🔗 Read more: Atomic and Hydrogen Bomb Differences Explained: Why One Is So Much Deadlier Than the Other

As Curiosity continues its climb up Mount Sharp, looking back at these dunes reminds us of just how much we've learned about the "modern" Mars—a planet that is still moving, still changing, and still very much full of surprises.