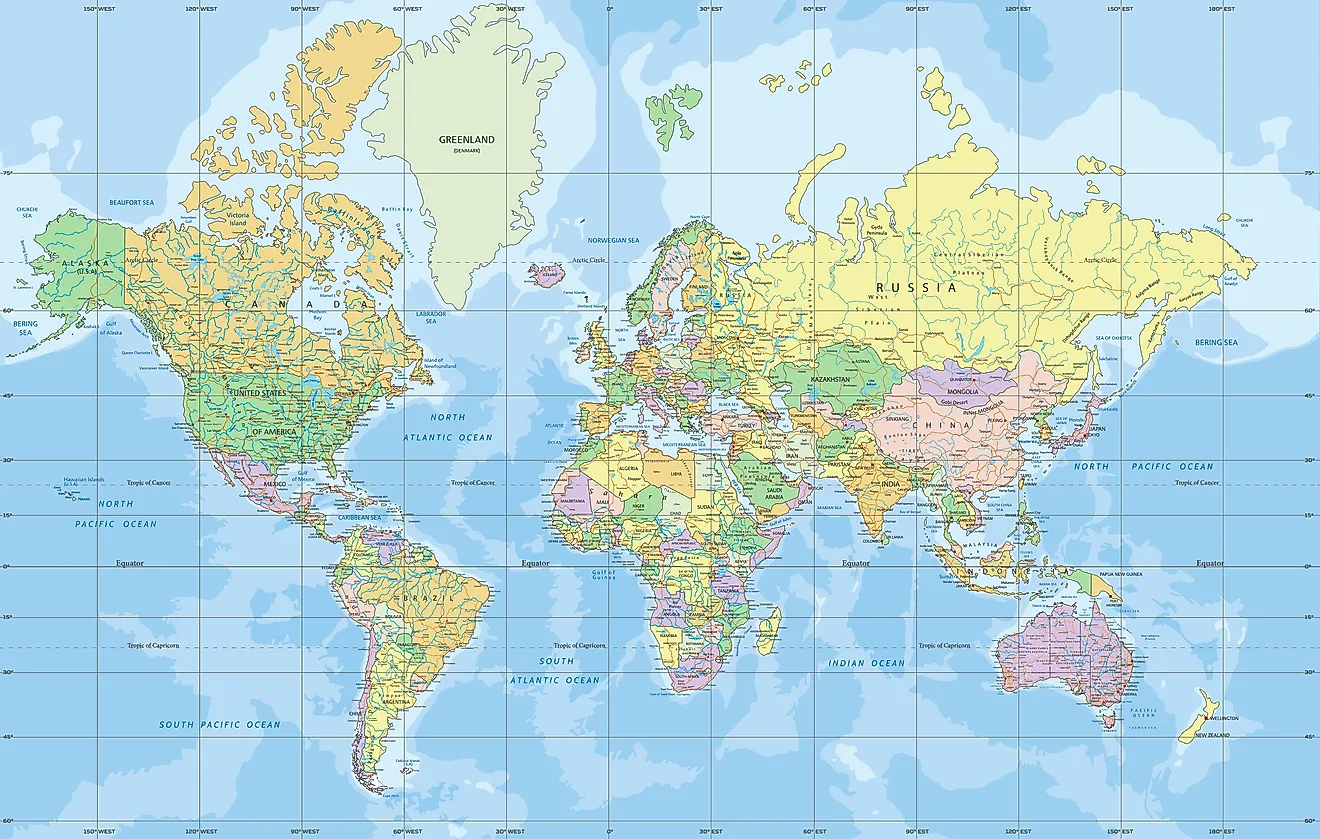

Look at a standard wall map in any classroom. Greenland looks like a massive, icy continent roughly the size of Africa. It dominates the North Atlantic. But honestly? It's a lie. A total geographic hallucination. In reality, Africa is about fourteen times larger than Greenland. You could fit Greenland, the United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside the African coastline with room to spare. Yet, the mercator projection map of world remains the most recognizable image of our planet. Why? It isn't because cartographers are lazy. It’s because this specific map solved a deadly problem for sailors in 1569, and we’ve been living with the trade-offs ever since.

Gerardus Mercator wasn't trying to teach children about the relative size of nations. He was a Flemish cartographer living in a time when "getting lost at sea" usually meant "dying of scurvy on a shipwreck." He needed a tool for navigation. Before his work, sailors struggled to plot straight-line courses on a curved earth. If you draw a straight line on a globe, it’s a "great circle" route, which is technically the shortest distance but requires constantly changing your compass heading. Mercator changed the game by distorting the grid. He stretched the spacing between latitude lines as they move away from the equator. This mathematical trick ensures that any straight line drawn on the map is a line of constant true bearing.

Sailors loved it.

🔗 Read more: Sky Go: What Most People Get Wrong About Streaming Your Subscription

They could just lay down a ruler, find their angle, and sail. It worked. It saved lives. But the price of that navigational precision was a massive distortion of area. The further you get from the equator, the more the map stretches everything out like a piece of taffy. This is why Antarctica looks like a never-ending white shelf at the bottom of the page and why Europe seems to rival South America in scale. It’s a trade-off. Accuracy of shape and direction vs. accuracy of size. You can't have both on a flat sheet of paper.

The Math Behind the Distortion

Geometry is stubborn. You cannot flatten a sphere without tearing it or stretching it. Think about peeling an orange. If you try to lay the peel flat, it rips. To keep the peel in one solid rectangle, you'd have to stretch the top and bottom edges until they are as wide as the middle.

In the mercator projection map of world, this stretching is calculated using a specific formula. The horizontal scale is constant everywhere, but the vertical scale increases with the secant of the latitude. As you approach the poles, the secant approaches infinity. That’s why you usually see Mercator maps cut off at about 85 degrees North and South; if they went all the way to 90 degrees, the map would literally be infinitely tall.

Modern critics, like those from the Boston Public Schools system which famously swapped Mercator for the Gall-Peters projection in 2017, argue that this isn't just a math problem—it’s a perception problem. When the "Global North" (Europe, North America, Russia) appears twice as large as it actually is, it subconsciously reinforces a sense of colonial superiority. It makes the tropical regions—where the majority of the world's population actually lives—look small and insignificant.

Why Google Maps Still Loves Mercator

You might think we’d have moved on by now. We have GPS. We have satellites. We have interactive 3D globes in our pockets. Yet, if you open Google Maps or Mapbox right now, you are looking at a variation called Web Mercator.

📖 Related: Why The Weather Channel Live YouTube Stream Is Actually Better Than Cable

Why? Because it preserves angles.

When you zoom into a street level in London or Tokyo, you want the street corners to look like 90-degree angles if they are actually 90-degree angles. If Google used an equal-area projection, the buildings and intersections would look skewed and tilted as you panned around. For local navigation, "shape" is king. If a park is a square in real life, you want it to be a square on your screen. Web Mercator keeps those local shapes recognizable.

Comparing the Mercator to the Rivals

People often point to the Gall-Peters projection as the "fix." It’s an equal-area map. On a Gall-Peters map, Africa is huge and Europe is tiny, which is geographically "fairer" in terms of surface area. But it has its own issues. To keep the areas correct, it stretches the continents vertically. Africa looks like it’s melting. South America looks like a long, thin teardrop. It’s ugly, and it’s just as "distorted" as Mercator, just in a different way.

Then there’s the Robinson Projection. Between 1988 and 1998, the National Geographic Society used this as their standard. It doesn't try to be perfect at anything. It distorts size a little and shape a little, but it "looks" right to the human eye. It’s a compromise. Nowadays, they’ve moved on to the Winkel Tripel projection, which is even better at minimizing the three types of distortion: area, direction, and distance.

- Mercator: Perfect for local navigation, terrible for understanding global scale.

- Gall-Peters: Perfect for area comparison, terrible for shapes.

- Winkel Tripel: The "Goldilocks" map that the pros use for general education.

- Dymaxion: Buckminster Fuller’s map that unfolds the earth into a 20-sided shape to show the world as one continuous landmass.

Honestly, the "best" map depends entirely on what you’re trying to do. If you're sailing from Lisbon to New York in a wooden sloop, Mercator is your best friend. If you’re a teacher trying to explain the geopolitical importance of the African continent, Mercator is your worst enemy.

The Tissot’s Indicatrix Test

If you want to see exactly how a map lies to you, look up "Tissot’s Indicatrix." It’s a clever tool used by cartographers where they place circles of equal size all over a globe. When you project that globe onto a flat map, you see those circles change.

On a mercator projection map of world, the circles stay perfect circles—they don't turn into ovals—but they get massive as they move toward the poles. A circle at the equator is a dot; a circle over Northern Canada is a giant hula hoop. This proves the "conformal" nature of the map. It preserves local shapes but fails the size test miserably.

Cartographer Arno Peters was quite vocal about this in the 1970s. He claimed the Mercator map was a tool of "cartographic imperialism." While that's a bit dramatic—Mercator was just trying to help sailors not hit rocks—the point remains that maps are powerful. They shape how we see our place in the world. If you grew up seeing Europe in the center and looking massive, you're going to have a skewed view of global importance.

Does it actually matter in 2026?

Actually, yeah. It does.

As we deal with global issues like climate change, the Mercator projection can be misleading. When people look at the melting ice caps on a Mercator map, the scale is so exaggerated that it’s hard to get an accurate visual sense of the rate of change relative to the rest of the planet. We need "spatial literacy." We need to be able to look at a screen and understand that what we are seeing is a representation, not a photo.

Actionable Insights for Using Maps

Since we can't escape the Mercator—it's baked into our digital infrastructure—the best we can do is be smarter consumers of geographic data. Here is how to handle the "Mercator Bias" in your daily life:

Use "The True Size Of" Tool

There is a fantastic website called thetruesize.com. It lets you drag countries around a Mercator map and watch them shrink or grow as they move across latitudes. Dragging the Democratic Republic of the Congo over Europe is a humbling experience. It covers almost the entire continent.

Switch to "Globe View"

Whenever you are using Google Maps on a desktop, zoom out all the way. Google eventually switches from a flat Mercator view to a 3D globe. Use this view when you are trying to understand the distance between two points on different continents. It’s the only way to see the "Great Circle" routes that planes actually fly.

Check the Projection on Infographics

If you see a data visualization showing something like "Global Wealth Distribution" or "CO2 Emissions," check the map projection. If they are using Mercator to show data that is area-dependent (like forest cover), the data is visually skewed. An equal-area map like the Mollweide or the Eckert IV is much better for statistical data.

Question the Center

Most Mercator maps are "Eurocentric" or "Americentric," meaning they split the Pacific Ocean in half. This makes it look like Asia and America are worlds apart. Try looking at a "Pacific-centered" map once in a while. It completely changes your perspective on the proximity of the US West Coast to East Asia and the vastness of the Pacific.

The mercator projection map of world isn't "wrong." It’s just a tool designed for a specific job that ended up becoming our default view of reality. It’s a 450-year-old navigation hack that we’ve mistaken for a portrait of the Earth. Once you see the distortion, you can't unsee it. And that’s the first step toward actually understanding what the world looks like.

Stop trusting the Greenland you see on the wall. It’s not that big. Africa is just that much more massive than you were taught. Explore different projections, use globe views for long-distance planning, and always remember that every flat map is a compromise between truth and utility.