Imagine walking through Paris in the late 1880s and seeing a giant, rusty-looking iron "asparagus" rising above the skyline. People were livid. Honestly, they thought it was the ugliest thing to ever happen to their city. Today, we call it the Paris Exposition of 1889, or the Exposition Universelle, but back then, it was a massive gamble that almost didn't happen because of European politics. It wasn't just about a tower, though. It was a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, which, as you can guess, made the neighboring monarchies pretty uncomfortable.

Russia and Great Britain basically ghosted the event at an official level. They weren't exactly thrilled to celebrate the day the French started chopping off royal heads. But despite the diplomatic drama, the world showed up anyway.

The Iron Monster Nobody Wanted

Guy de Maupassant, the famous writer, used to eat lunch at the Eiffel Tower’s restaurant every single day. Why? Because it was the only place in Paris where he didn't have to look at the tower. He called it a "giant ungainly skeleton." He wasn't alone. A group of artists and architects even signed a manifesto calling it a "hateful column of bolted tin."

💡 You might also like: Why Everyone Stops at Little Czech Bakery West TX (And What to Actually Order)

Gustave Eiffel didn't care. He was a bridge builder, not an "artist" in the traditional sense, and he saw the Paris Exposition of 1889 as a chance to prove that iron was the future of architecture. The tower was only supposed to stay up for 20 years. It was essentially a giant pop-up shop for French engineering. It stood at 300 meters, which was a big deal because it smashed the record held by the Washington Monument.

People were terrified it would fall over. They thought the wind would catch those iron beams and just topple it onto the houses nearby. Instead, it became the biggest tourist draw in human history. Over 1.9 million people paid to go up during the fair, and they did it using hydraulic elevators that were, frankly, terrifyingly advanced for the time. Otis Brothers & Co. from America actually designed some of these lifts, which was a bit of a sting to French pride, but they worked.

Electricity and the End of the Dark Ages

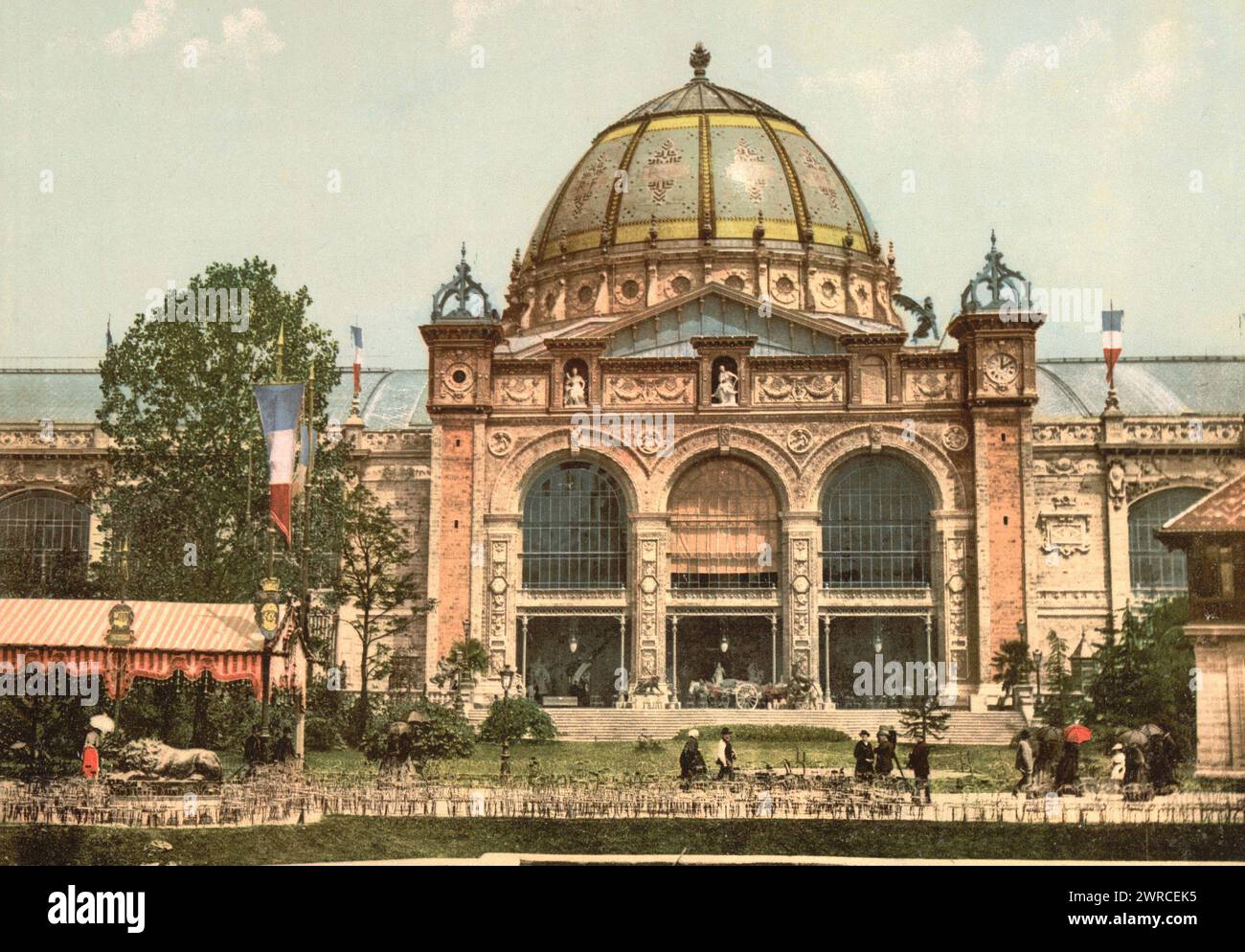

If the tower was the bones of the Paris Exposition of 1889, electricity was its soul. You have to remember that most people were still using gas lamps or candles. Then, suddenly, they walk onto the Champ de Mars and see the Palais des Machines.

This building was insane. It had a span of 115 meters without any internal pillars. Nothing like it had ever been built. Inside, it was filled with the hum of dynamos and the glow of electric light bulbs. Edison was there, of course. Thomas Edison had a massive pavilion where he showed off the phonograph. People stood in line for hours just to hear a recording of a voice. It felt like sorcery.

The "Illuminated Fountains" were the real showstopper. Using colored glass and electric arc lamps, the water changed colors in sync with music. This seems basic to us now—basically a low-tech version of the Bellagio in Vegas—but in 1889, it was the closest thing to a sci-fi movie anyone had ever seen. It changed the way people thought about the night. Suddenly, darkness wasn't something to fear; it was a canvas for light.

The Controversy of the "Human Zoo"

We can't talk about the Paris Exposition of 1889 without talking about its darkest side: the Village Annamite and the Negro Village. This is where the "expert" history gets uncomfortable. France was a colonial power, and they wanted to flex. They brought in nearly 400 people from colonies like Senegal, Gabon, and Indochina to live in reconstructed villages.

It was billed as "anthropological," but it was essentially a human zoo. Visitors paid to watch people perform daily tasks, weave rugs, or dance. It was meant to show the "civilizing mission" of France. While it was a huge hit with the public—millions of people visited these displays—it’s a stark reminder that the "progress" celebrated at the fair was built on a foundation of deep-seated racism and imperial ego.

A Gastronomic Revolution on the Champ de Mars

The food situation at the Paris Exposition of 1889 was also kind of a mess, but in a good way. Because so many international delegations showed up, you had this weird fusion of cultures happening on the streets of Paris. You could get American-style cocktails (still a novelty in France) or couscous from Algeria.

Restaurants were built directly into the first platform of the Eiffel Tower. There was a Russian restaurant, a French one, and even a bar. People would spend the whole day there. They weren't just looking at machines; they were drinking champagne at 300 feet in the air. This was the birth of "event dining" as we know it.

Quick Facts Most People Forget

- The tower was originally painted "Venetian Red."

- Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show was a massive hit outside the main fairgrounds. Annie Oakley was there, and Parisians went absolutely nuts for the "cowboy" aesthetic.

- The fair ran from May to November, and by the end, it had actually turned a profit, which almost never happens with World's Fairs.

- The total attendance was roughly 32 million people. In 1889. That's a staggering number when you consider travel was done by steamship and train.

The Architecture of the Impossible

The Palais des Machines was arguably more impressive than the tower to the engineers of the day. Designed by architect Ferdinand Dutert and engineer Victor Contamin, it used "three-hinged arches." This allowed the massive metal structure to expand and contract with the temperature without cracking.

Basically, the building breathed.

Walking through it was described as feeling like you were inside the ribcage of a leviathan. It was filled with the sounds of weaving machines, printing presses, and steam engines. It was loud, hot, and smelled like oil, but it represented the peak of the Industrial Revolution. It's a shame they tore it down in 1910. Most people agree now that it was a huge architectural mistake to get rid of it.

Why the Paris Exposition of 1889 Still Matters

The legacy of this event isn't just a postcard of a tower. It’s the moment the modern world decided what it wanted to look like. It popularized the idea that technology should be beautiful, not just functional. It also cemented Paris as the "Capital of the World" for the next several decades.

Even the way we experience cities today—the streetlights, the elevators, the concept of a "must-see" monument—traces back to those six months on the Champ de Mars. It was the first time the global public collectively realized that the future was going to be fast, bright, and made of steel.

How to Explore This History Today

If you're heading to Paris and want to see more than just the surface-level stuff, here is how you actually find the remnants of 1889:

- Visit the Musée Carnavalet: This is the museum of the history of Paris. They have incredible artifacts from the fair, including original tickets and posters that aren't the mass-produced ones you see in souvenir shops.

- Check out the Cité de l'Architecture et du Patrimoine: They have large-scale models of the fairgrounds. It’s the best way to understand the scale of the Palais des Machines compared to the tower.

- Walk the Champ de Mars at night: Look at the base of the Eiffel Tower's pillars. You can still see some of the original masonry and engineering details that Gustave Eiffel insisted on to keep the "monster" from sinking into the Seine's soft soil.

- The Musée d'Orsay: While the building itself was for the 1900 fair, it houses many of the paintings and sculptures that were first debuted or celebrated during the 1889 era. It gives you the "vibe" of the Belle Époque better than anywhere else.

The Paris Exposition of 1889 was a messy, brilliant, controversial, and loud explosion of human ambition. It showed us that humans can build the impossible, even if half the city complains about it the whole time.