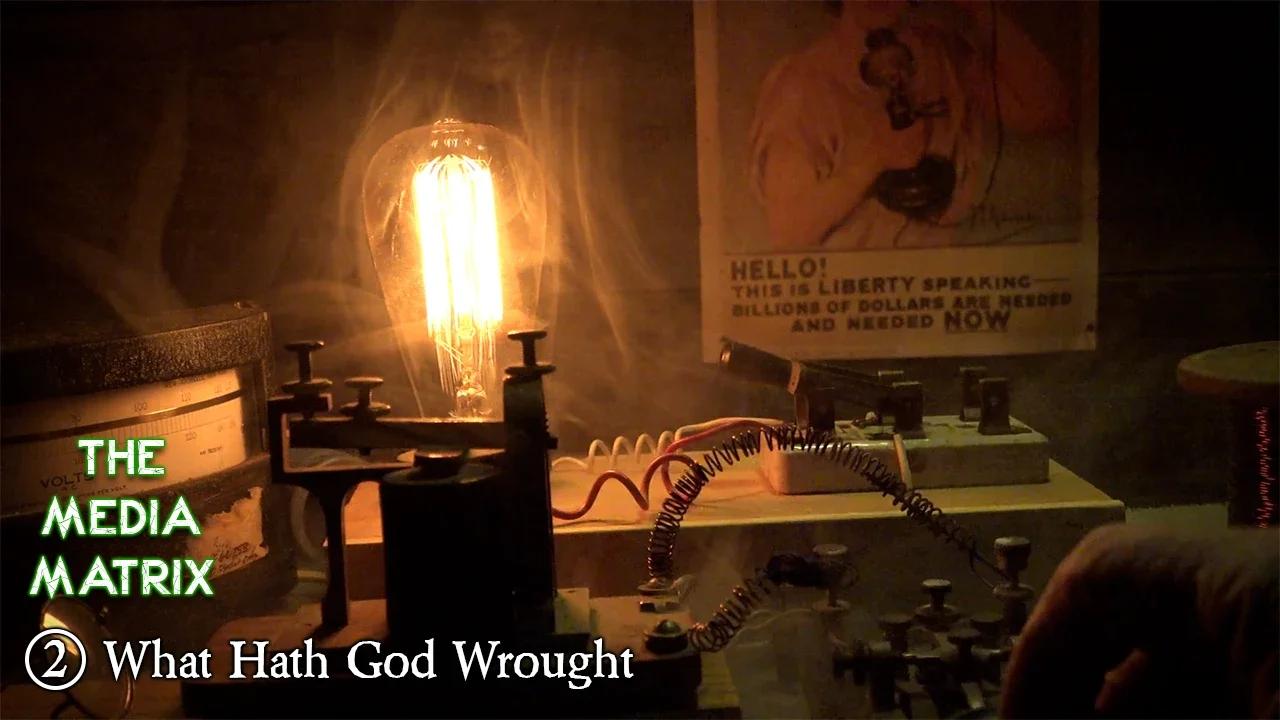

On May 24, 1844, a man named Samuel Morse sat in the Supreme Court chamber in Washington, D.C. He wasn't there for a trial. He was there to change how the world talks. He tapped out a series of dots and dashes on a clunky metal machine, and seconds later, those same pulses appeared in Baltimore. The message was simple: What God hath wrought.

It’s a phrase from the Bible, specifically Numbers 23:23. Annie Ellsworth, the daughter of the Patent Commissioner, actually picked the words. She probably didn't realize she was naming the birth of the telecommunications age. Honestly, we usually think of the internet as this "new" thing, but the spirit of the modern web started right there in that courtroom. Before that moment, news traveled as fast as a horse could gallop. After that? Information moved at the speed of light.

The Day the World Shrank

Imagine living in a world where a letter from your cousin in another state took two weeks to arrive. If there was a war, you might not know it was over until a month after the treaty was signed. That was the reality before what god hath wrought became a reality. Morse wasn't the only guy trying to figure this out—folks like Charles Wheatstone and William Cooke in England were working on their own versions—but Morse’s system was the one that stuck because of its elegant simplicity.

It wasn't just a technical win. It was a psychological shock.

People at the time were genuinely freaked out. Some thought the wires were literal pipes that carried pieces of paper. Others thought it was dark magic. When you think about it, the leap from "horse-carried mail" to "invisible electric pulses" is way bigger than the leap from a flip phone to a smartphone. We’re used to tech jumping ahead now. They weren't.

Why the Phrase Mattered

Morse was a deeply religious man. By choosing what god hath wrought, he wasn't just being humble; he was acknowledging that this new power felt almost divine. It was "annihilating space and time," as people liked to say back then.

If you look at the original paper tape from that day—which is currently sitting in the Library of Congress—you can see the tiny indentations. It doesn't look like much. Just some messy marks on a thin strip of paper. But those marks meant that a person in D.C. could "speak" to a person in Baltimore instantly. It was the first "What's up?" text in human history.

Building the Victorian Internet

The growth was explosive. Within ten years, over 20,000 miles of telegraph wire crisscrossed the United States. It changed everything.

Take the news business, for example. Before the telegraph, newspapers were local and slow. Afterward, the Associated Press was born because papers realized they could share the cost of telegraphing news from the front lines of the Mexican-American War. Suddenly, a guy in New York was reading about a battle that happened in Texas yesterday.

✨ Don't miss: Why an LCD Writing Tablet for Adults is the Most Underrated Productivity Tool Right Now

It changed business too.

Stock prices became uniform. Before the telegraph, the price of wheat in Buffalo might be totally different from the price in New York City because nobody knew what the other guy was charging. The telegraph leveled the playing field. It created the "ticker" and made the modern financial market possible.

The Struggles Nobody Mentions

It wasn't all smooth sailing. Setting up those lines was a nightmare.

- Weather: Storms knocked down poles constantly.

- Vandalism: People would cut the wires because they thought they caused bad crops or were just plain suspicious.

- Cost: Sending a telegram was incredibly expensive. It wasn't for casual "hey" messages; it was for "Grandma died" or "Buy 100 shares of Union Pacific."

Morse himself spent years in court fighting over patents. Everyone wanted a piece of the action. It's the same thing we see today with Big Tech lawsuits. Different era, same human greed.

From Copper Wires to Fiber Optics

You might wonder why we’re still talking about a 180-year-old message.

It’s because the logic of the telegraph is the logic of the internet. Morse code is binary. It’s on or off. Short or long. Our entire digital world is built on 1s and 0s, which is basically just a faster version of Morse’s dots and dashes.

When the first transatlantic cable was laid in 1858, Queen Victoria sent a message to President James Buchanan. It took 17 hours to get across the ocean, which sounds slow now, but compared to the weeks it took by ship? It was a miracle. That cable was the direct ancestor of the fiber optic lines that currently sit on the ocean floor, carrying your Netflix stream and your Zoom calls.

We often forget that "the cloud" is actually a bunch of cables.

The Social Impact

The telegraph changed how we write. Since you paid by the word, people got really brief. They skipped "the," "a," and "and." It was the 19th-century version of "u r here." This "telegraphic style" eventually influenced writers like Ernest Hemingway, who stripped down his prose to be lean and direct.

It also created the first "online" communities. Telegraph operators would sit at their keys for hours. They got to know operators in other cities. They played chess over the wires. They told jokes. They even had their own slang. They were the first people to live a portion of their lives "in the wires," separate from their physical location.

What Most People Get Wrong About Morse

There's a common myth that Morse invented the telegraph in a vacuum. He didn't.

He was an artist first—a painter, actually. He got interested in electricity after his wife died suddenly and he didn't get the news until she was already buried. That grief fueled his obsession with speed. But he needed help.

Alfred Vail was the guy who actually refined the code and built much of the hardware. Joseph Henry provided the scientific understanding of electromagnetism that made long-distance transmission possible. Morse was the visionary and the bulldog who got the funding from Congress, but he wasn't a lone genius.

Tech is always a team sport.

The Message Today

In 2026, we’re looking at AI and quantum computing. We’re saying the same things Morse’s contemporaries said. We talk about "god-like" technology and the end of the world as we know it.

The phrase what god hath wrought serves as a reminder. It reminds us that every time we invent a new way to communicate, we think it's going to save the world—or end it. Usually, it does a little of both. It makes us more connected, but it also makes life faster and more stressful.

Actionable Insights for the Digital Age

Looking back at the history of the telegraph gives us some pretty clear clues on how to handle the "next big thing" in tech.

1. Don't fear the speed, master the filter.

Just like the telegram forced people to be concise, the modern world forces us to filter. You don't have to respond to every "ping" just because it's instant. Morse’s invention made the world faster, but it didn't make humans any better at processing information. That's on us.

2. Physical infrastructure still matters.

We talk about the "wireless" world, but everything relies on physical things. Cables, servers, and power plants. Understanding where your data actually goes—and who owns the "wires"—is more important now than it was in 1844.

3. Communication isn't connection.

The telegraph could send a message across the country, but it couldn't make two people understand each other. Don't mistake the ease of sending a message for the quality of the relationship.

4. Watch the "Binary" shift.

Everything in our world is moving toward a binary, data-driven model. While that's efficient (thanks, Morse!), don't lose the nuance. The "dots and dashes" of data can't capture everything about the human experience.

If you want to dive deeper into this, go look at the original Morse-Vail telegraph at the Smithsonian. It’s tiny. It’s simple. And it’s the reason you’re able to read these words on a screen right now. We’re all just living in the world that Morse—and whatever forces he was acknowledging—started building two centuries ago.

Next time you send a text, realize you’re just tapping on a glass version of Morse’s key. The tech changed. The human need to be heard didn't.