Engineers are kinda obsessed with making things smaller. It's a weird compulsion. We see it in microchips, we see it in medical devices, and for decades, we’ve seen it in internal combustion. When you think of a "small" engine, your brain probably goes to a weed whacker or maybe a remote-controlled car. Those are big. Huge, actually, compared to what’s really out there. The hunt for the smallest two stroke engine isn't just about hobbies; it's about the physics of how much power you can cram into a space smaller than a thimble.

It’s about friction. It’s about heat.

If you go too small, the oil molecules are basically too "fat" to lubricate the moving parts. The physics break down. Yet, people keep pushing the limit.

The Cox .010: The King of Tiny Production Engines

Most enthusiasts will tell you the conversation starts and ends with the Cox .010 Tee Dee. It’s a legend. Released in the early 1960s by L.M. Cox Manufacturing Co., this thing is basically a miracle of mass production. It has a displacement of just 0.00997 cubic inches. To put that in perspective for those of us who don't think in decimals, that’s about 0.16 cubic centimeters.

It weighs next to nothing. About 14 grams. That’s roughly the weight of three nickels.

When you see one in person, it looks like a piece of jewelry, not a functional power plant. But it screams. This smallest two stroke engine in the commercial world can hit 30,000 RPM. Think about that for a second. The tiny piston is moving up and down five hundred times every single second. At that scale, the tolerances have to be insane. We’re talking about fits measured in millionths of an inch. If you get a speck of dust in the cylinder, the engine is basically junk.

The fuel is also weird. You can’t just go to the gas station. These tiny glow engines run on a mix of methanol and nitromethane, with a heavy dose of castor oil for lubrication. Because the engine is so small, it doesn't have a traditional carburetor with a float bowl. It uses a simple needle valve.

Honestly, starting one is an art form. You don't pull a cord; you flick the tiny propeller with your finger or a starter stick. If you've never heard a Cox .010 run, it doesn't sound like a motor. It sounds like a very angry hornet trapped in a tin can.

Why Two-Stroke?

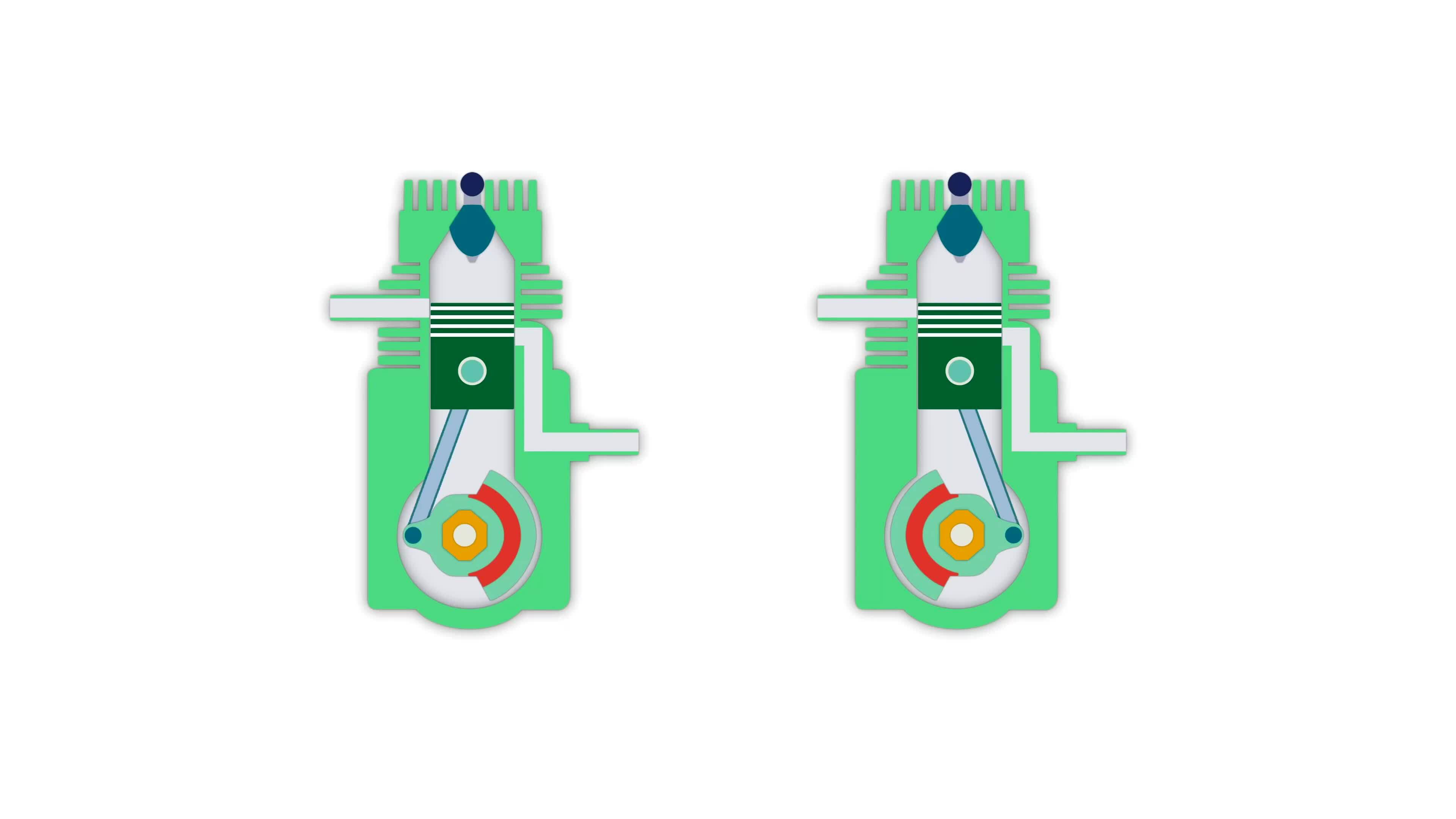

You might wonder why nobody makes a four-stroke this small. Well, they try, but it's a nightmare. A four-stroke needs valves. It needs a camshaft. It needs a timing belt or gears. When you're dealing with a total engine size smaller than your fingernail, you simply don't have room for all those extra bits.

The two-stroke is the perfect candidate for the smallest two stroke engine title because of its brutal simplicity. You have three moving parts: the piston, the connecting rod, and the crankshaft. That’s it. The engine uses ports in the cylinder wall instead of mechanical valves. As the piston moves, it uncovers the holes to let air in and exhaust out. It’s elegant. It’s also incredibly inefficient and dirty, but at this scale, who cares about emissions? You’re burning a thimbleful of fuel every ten minutes.

Pushing into the Micro-World: The MEMS Engines

While the Cox is the smallest you can actually buy on eBay and fly in a model plane, researchers have gone much, much smaller. This is where we enter the world of Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS).

In the early 2000s, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, led by Professor Carlos Fernandez-Pello, worked on what they called the "micro-rotary engine." It wasn't a traditional piston engine, but it followed similar combustion cycles. They were trying to create a power source that could replace batteries.

Liquid fuel has a much higher energy density than even the best lithium-ion batteries.

- A battery stores energy chemically.

- Gasoline stores energy in carbon bonds.

- The gap in potential energy is massive.

They built a "wankel" style engine out of silicon and steel that was smaller than a dime. We're talking millimeters here. However, these engines face a massive hurdle: heat loss. Because the engine is so small, the surface area is huge compared to the volume of the combustion chamber. The heat from the explosion just soaks into the metal and disappears before it can push the rotor. It's like trying to start a campfire with a single match in the middle of a blizzard.

The Nanotech Frontier and The "Single Atom" Engine

If we want to get pedantic—and in the world of the smallest two stroke engine, we definitely do—we have to look at the University of Mainz in Germany. In 2016, a team of physicists built an engine consisting of a single atom. Specifically, a trapped Calcium-40 ion.

Is it a two-stroke? Not in the way your lawnmower is. But it operates on a thermodynamic cycle. They use a laser to heat the atom and then let it cool, causing it to vibrate in a trap. This vibration acts like a piston.

It’s obviously not going to power your RC plane. But it proves that the concept of a "heat engine"—taking energy from a temperature difference and turning it into motion—works even at the scale of quantum mechanics. It’s the ultimate end of the line. You literally cannot get smaller than a single atom.

Real-World Use Cases for Tiny Engines

Why do we do this? Is it just for bragging rights? Sorta. But there are real applications.

- Military Reconnaissance: Tiny drones (Black Hornet size) need power. While most are electric now, small liquid-fuel engines offer longer flight times because of that energy density advantage I mentioned earlier.

- Medical Implants: There was a period where researchers looked at micro-engines to power heart pumps. The idea was to have a tiny reservoir of high-energy fuel that could last longer than a battery.

- Sensor Hubs: In remote areas, a tiny engine could theoretically run a generator to power weather sensors for months on a single pint of fuel.

The Problem with Scale

The reason you don't see a smallest two stroke engine in every piece of tech is because of the "Square-Cube Law."

As you shrink an engine, the volume (which provides the power) decreases much faster than the surface area (which creates friction). A tiny engine has a lot of "skin" relative to its "guts." Friction becomes the dominant force. In a car engine, friction is a small percentage of energy loss. In a micro-engine, friction can be 50% or more of the total energy produced.

Then there’s the fuel. At tiny scales, fuel doesn’t want to vaporize. It stays in big, fat droplets. Big droplets don't burn fast enough.

🔗 Read more: Thirty Years of Adonis: How One Project Refined the Modern Web

What the Experts Say

I talked to a few guys who spend their weekends machining "home-built" micro engines. One of them, a retired machinist named Art, told me that "the smaller you go, the more the air feels like molasses."

To a tiny piston, air isn't a gas; it's a viscous fluid. This is a nuance most people miss. You aren't just fighting the metal; you're fighting the atmosphere itself. This is why the smallest two stroke engine designs often look so different from their larger cousins. They have massive intake ports and very "loose" tolerances when cold, because once they fire up, the heat expansion is relatively enormous.

How to Get Involved with Micro Engines

If you’re fascinated by this, don’t try to build a single-atom engine in your garage. Start with the classics.

The hobby of "Model Engineering" is alive and well. People like the late Joe Martin (of Sherline Products) championed the idea of "micro-machining." You can still find plans for engines like the "Nano-C" or various tiny diesel conversions.

Keep in mind: these are not "set it and forget it" machines. They require a specific touch. You need to understand needle valve settings, fuel pressures, and how to read the "smoke" from an exhaust port that’s the size of a pinhead.

Actionable Insights for the Miniature Enthusiast

If you want to own or work with the smallest two stroke engine technology available today, here is the path forward:

- Source a Vintage Cox .010: Check eBay or specialized estate sales. Be prepared to pay a premium; these are no longer in production and are highly sought after by collectors. Ensure the "glow plug" (the head of the engine) is intact, as replacements are getting harder to find.

- Study High-Nitro Fuels: Small engines need more "kick." Standard 10% nitro fuel won't cut it. You’ll likely need 25% to 35% nitromethane to get reliable combustion in a sub-1cc engine.

- Invest in a Tachometer: At this scale, you can't trust your ears. An optical tachometer will tell you if you're hitting the 30,000 RPM sweet spot or if you're running too lean and about to melt your piston.

- Focus on Cleanliness: Use a surgical-grade fuel filter. A single microscopic grain of sand will score the cylinder of a micro-engine and ruin the compression forever.

The world of the smallest two stroke engine is a testament to human ingenuity. It's a reminder that physics doesn't just change at the edges of the universe—it changes right in the palm of your hand. Whether it's a 1960s hobby motor or a modern MEMS research project, these tiny machines prove that power doesn't always have to be big to be impressive.

Check your local hobby shops or engineering forums. There is a whole community of people obsessed with the "tiny," and the technical hurdles they overcome daily are nothing short of incredible.