Physics is usually a slow burn. Most years, we just get incremental data or another decimal point added to a constant we already knew. But 2006 was different. It felt like the air in the theoretical physics community was buzzing with a mix of desperation and radical ego. If you look back at the theory of everything 2006 landscape, you aren’t looking at a single discovery. You're looking at a civil war.

It was the year the "String Theory Wars" officially went nuclear.

For decades, String Theory was the only game in town. It promised to bridge the gap between the gargantuan world of General Relativity and the twitchy, unpredictable world of Quantum Mechanics. But by 2006, the honeymoon was over. People started asking, "Where are the results?"

The Year String Theory Got Punched in the Mouth

Two massive books hit the shelves in 2006, and they basically took a sledgehammer to the ivory tower. First, you had Lee Smolin’s The Trouble with Physics. Then came Peter Woit’s Not Even Wrong. These weren't just dry academic papers; they were manifestos. They argued that the search for the theory of everything 2006 had turned into a "cult of string theory" that didn't actually make any testable predictions.

Woit’s title was a direct jab. He borrowed a phrase from Wolfgang Pauli to describe a theory that is so vague it can't even be proven false. That’s a death sentence in science. If you can’t be wrong, you can’t be right either.

Smolin, a heavy hitter from the Perimeter Institute, argued that the physics community was putting all its eggs in one basket. He was pushing Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG) as the underdog alternative. While String Theory says everything is made of tiny vibrating strings in 10 or 11 dimensions, LQG suggests that space itself is made of discrete "chunks." Basically, space is like a piece of chainmail, not a smooth fabric.

Garrett Lisi and the E8 Emergence

While the big names were fighting, 2006 was also the year a "surfer physicist" named Antony Garrett Lisi was quietly finishing up a paper that would explode a year later. It was based on the E8 Lie group. Now, E8 is this mind-bendingly complex 248-dimensional mathematical structure. Lisi thought he could fit every known particle and force into the points of this shape.

✨ Don't miss: Why Thinking About Me and You Together Changes How We Use AI

It was the ultimate "Theory of Everything" pitch.

Most people love the image of a guy living in a van in Maui solving the universe. It’s a great story. But in 2006, the groundwork for this "An Exceptionally Simple Theory of Everything" was being laid. It showed that the quest wasn't just happening in the halls of Harvard or Princeton. There was this sense that the "next Einstein" might come from outside the system because the system was stuck.

What about the Large Hadron Collider?

You can't talk about the theory of everything 2006 without talking about the wait. The LHC at CERN was still two years away from being powered up. The world of physics was in a holding pattern. We had these massive theories, but zero data to back them up.

Everything was math.

Think about that for a second. We were building the most expensive machine in human history because our math said something should be there (the Higgs Boson), but we weren't 100% sure. In 2006, the tension was at an all-time high. If the LHC found nothing, String Theory was essentially dead. If it found the Higgs, it confirmed the Standard Model, but still didn't explain gravity. It was a weird, anxious time to be a nerd.

The Maldacena Influence

In the middle of all this controversy, the work of Juan Maldacena was still the gold standard for those sticking with strings. His "AdS/CFT correspondence" (from a few years prior but peaking in influence around 2006) suggested a holographic universe. This isn't sci-fi. It’s the idea that the gravity in a 3D volume can be described by a quantum theory on its 2D boundary.

Imagine a soda can. Everything happening inside the liquid can be explained by looking at the label on the outside.

This was the strongest lead anyone had for a the theory of everything 2006 could offer. It linked gravity and quantum field theory in a way that actually made sense mathematically, even if it was impossible to visualize.

Dark Energy and the Anthropic Principle

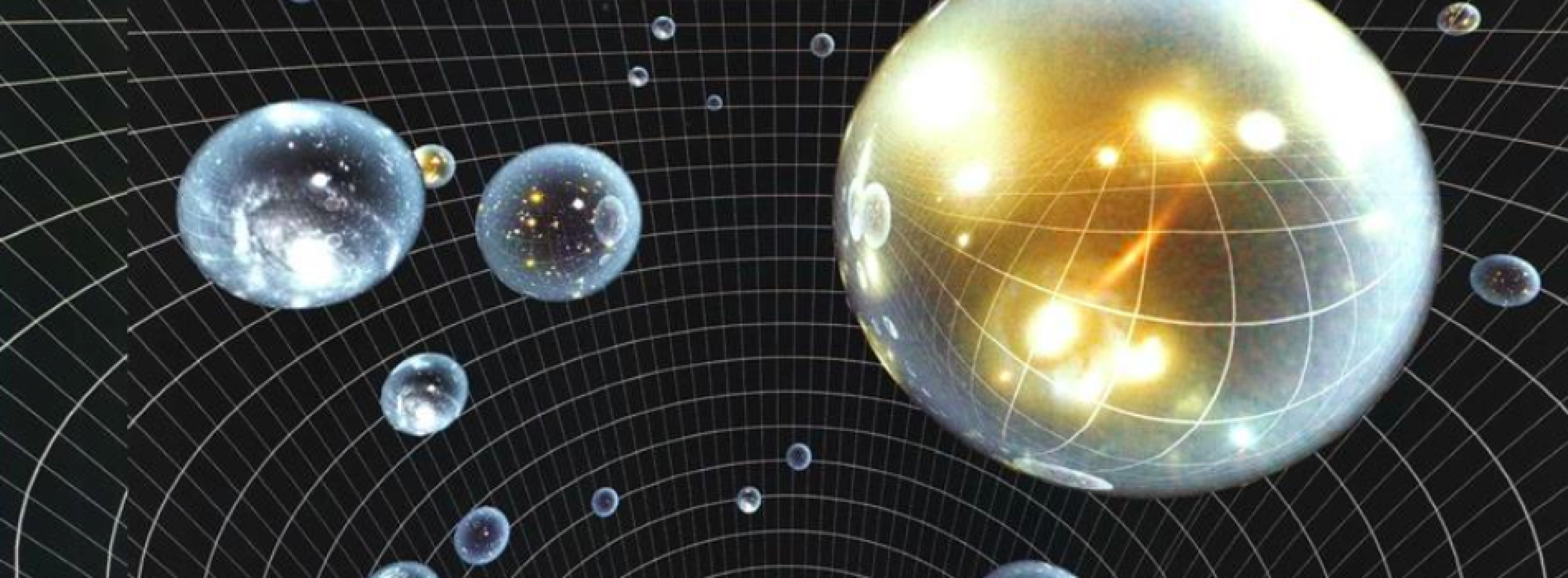

2006 was also the year we started grappling with the "Landscape." String Theory doesn't just give you one universe. It gives you $10^{500}$ possible universes.

That’s a 1 with 500 zeros after it.

Leonard Susskind, one of the fathers of String Theory, started leaning into the Anthropic Principle. He basically said, "Look, maybe our universe is just a tiny bubble in a massive Multiverse. Maybe the laws of physics are the way they are just because if they weren't, we wouldn't be here to ask the question."

A lot of physicists hated this. It felt like giving up. It felt like saying "it is what it is" instead of finding a fundamental law. It sparked a massive philosophical rift that still exists today. Are we looking for a single equation you can fit on a T-shirt, or are we just one random accident in a sea of chaos?

Why 2006 Still Matters Today

Honestly, we haven't solved it yet. The the theory of everything 2006 debates are still the same debates we’re having now, just with better telescopes. We still don't know if space is "chunky" or if everything is a string. But 2006 was the year the "String Theory monopoly" broke. It forced physicists to be more honest about what they actually knew versus what they were just hoping was true.

It taught us that math can be beautiful and still be completely wrong about reality.

If you want to understand where physics is going, you have to look at those 2006 arguments. They defined the boundaries of the modern search for the "God Equation." We learned that elegance isn't a substitute for evidence. We also learned that sometimes, the most radical ideas come from the people willing to say "the king has no clothes."

Actionable Insights for the Physics Enthusiast

If you're trying to keep up with the current state of a unified theory, don't just read the textbooks. Follow the debates.

- Read the "Big Two" Critiques: Pick up The Trouble with Physics by Lee Smolin. It’s incredibly readable and explains why the structure of academic science might be holding back the next big discovery.

- Track the LHC Upgrades: The 2006 hype was about the possibility of the LHC. Now, we are looking at High-Luminosity upgrades that will probe even deeper into "New Physics" like dark matter candidates.

- Explore Loop Quantum Gravity: If you're bored of String Theory, look into the works of Carlo Rovelli. His book Reality Is Not What It Seems is a perfect gateway into the "chunky space" theory that gained momentum in 2006.

- Don't ignore the math: You don't need a PhD to understand the implications of the E8 Lie group or Holography. Look for visual explanations of the AdS/CFT correspondence to understand how we might actually live in a holographic projection.

The quest for a unified theory is still the greatest detective story in history. We're just waiting for the next 2006 to shake things up again.