You’ve probably seen the standard U.S. mountain ranges map in a third-grade classroom. It’s usually a green and brown blobby mess with some jagged lines representing the Rockies and the Appalachians. It looks simple. It looks settled. But honestly, those maps are kinda lying to you. They oversimplify the sheer chaos of North American geology.

Most people think of mountains as just "high places" where you go to ski or hike. In reality, a map of U.S. mountain ranges is a literal timeline of the planet’s violent history. We are talking about tectonic plates smashing into each other like slow-motion freight trains, volcanic eruptions that make Mount St. Helens look like a firecracker, and the slow, agonizing grind of glaciers carving out valleys. When you look at a map, you aren't just looking at geography; you are looking at a 1.2 billion-year-old crime scene.

The East Coast vs. West Coast Divide

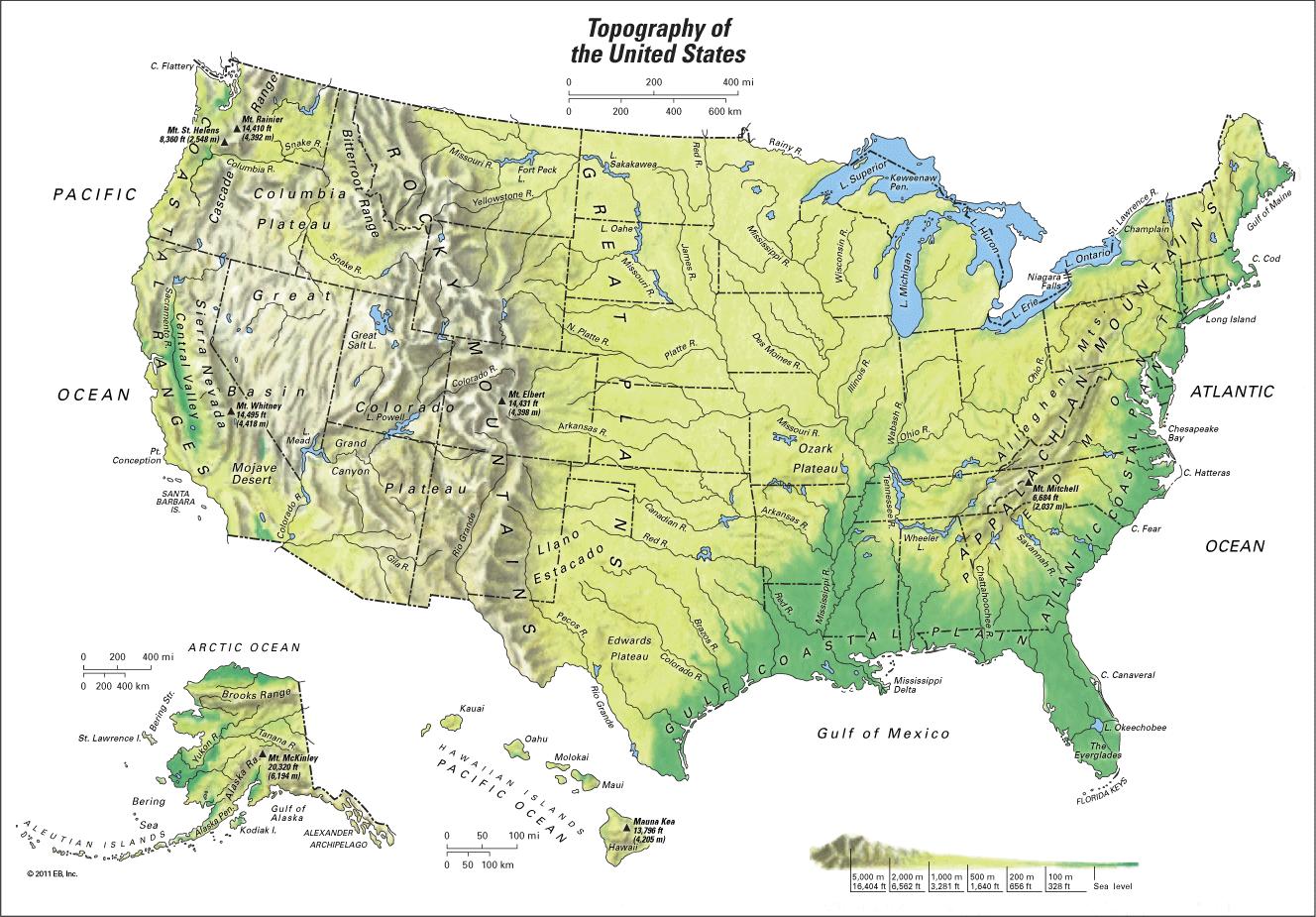

If you look at a U.S. mountain ranges map, the first thing you notice is the massive difference between the two sides of the country.

The Appalachians are old. Like, really old. We are talking 480 million years. Back then, they were likely as tall and jagged as the Himalayas are today. But time is a thief. Hundreds of millions of years of rain, wind, and ice have sanded them down into the rolling, forest-covered ridges we see today. They stretch from Alabama all the way up into Canada, but they aren't a single "wall." They are a series of distinct provinces like the Blue Ridge, the Ridge and Valley, and the Allegheny Plateau.

Then you look West.

The Rockies are the heavy hitters. They’re younger, sharper, and much more aggressive. While the Appalachians were formed by the closing of the Iapetus Ocean, the Rockies were born from the Laramide Orogeny. This was a weird geological event where a tectonic plate slid underneath North America at a shallow angle, causing the crust to buckle way further inland than it usually does. That’s why the Rockies are in Colorado and Montana instead of right on the coastline. It’s also why they have those iconic, snow-capped peaks that stay white well into July.

The Hidden Complexity of the Intermountain West

This is where your average U.S. mountain ranges map starts to get confusing. Between the Rockies and the Sierra Nevada lies a region geologists call the Basin and Range Province.

It looks like a "washboard" from space. Basically, the Earth’s crust is being pulled apart here. As the crust stretches, blocks of land drop down (the basins) and others tilt upward (the ranges). Nevada alone has over 300 mountain ranges. Think about that. Most people can't name three of them. You’ve got the Ruby Mountains, the Snake Range, and the Toiyabe Range, all sitting in this high-desert landscape that looks like another planet.

And then there's the Sierra Nevada.

One massive block of granite. That’s essentially what it is. It tilted up on its eastern edge, creating that dramatic, terrifying drop-off into the Owens Valley. If you’re standing at the top of Mount Whitney—the highest point in the contiguous U.S. at 14,505 feet—you’re basically standing on a giant piece of cooled magma that rose from deep within the Earth millions of years ago.

The Pacific Ring of Fire Influence

Don't forget the Cascades. They are different from the Rockies or the Sierras because they are volcanic. When you look at a map of mountain ranges in the Pacific Northwest, you’re looking at a line of "sleeping giants."

- Mount Rainier: The most topographically prominent peak in the lower 48.

- Mount Shasta: A massive stratovolcano that dominates the Northern California skyline.

- Mount St. Helens: The one that reminded everyone in 1980 that these mountains are very much alive.

These aren't just piles of rock; they are vents for the Earth’s internal heat. They exist because the Juan de Fuca plate is subducting—sliding under—the North American plate, melting rock as it goes.

Why the Ozarks Aren't Actually Mountains

Here is a fun fact that ruins dinner parties: The Ozarks are technically a plateau.

If you look at a U.S. mountain ranges map, the Ozarks in Missouri and Arkansas often get shaded like mountains. But geologically, they are an "uplifted plateau." Instead of the land being pushed up into peaks, the surrounding land was eroded down by rivers. The "peaks" you see are actually just the original level of the plateau that hasn't been washed away yet. It’s a subtle distinction, but to a geologist, it’s a big deal.

Alaska and Hawaii: The Map's Outliers

We usually focus on the lower 48, but that's a mistake. Alaska is home to the real monsters. The Alaska Range contains Denali, which is so big it creates its own weather systems. It’s over 20,000 feet tall. To put that in perspective, if you put the highest peak in the Rockies on top of a 6,000-foot pedestal, it still wouldn't reach the top of Denali.

🔗 Read more: Tampa to Salt Lake City Utah: Why This Cross-Country Route is the Ultimate Culture Shock

And Hawaii? It’s a mountain range that just happens to be mostly underwater. Mauna Kea is technically taller than Everest if you measure from its base on the ocean floor. We just only see the very tip of it poking out of the Pacific.

Navigating the Map for Real-World Use

If you’re actually trying to use a U.S. mountain ranges map for travel or planning, you need to understand "Prominence" versus "Elevation."

Elevation is how high the peak is above sea level. Prominence is how much the mountain stands out from the land around it. A mountain can have a high elevation but low prominence if it’s just a small bump on a high plateau. Conversely, a mountain like Mount Rainier has massive prominence because it rises nearly 14,000 feet straight up from the surrounding lowlands.

When you're looking at a topographic map, look for the "contour lines." The closer they are, the steeper the terrain.

Practical Steps for Your Next Trip

Stop looking at flat 2D maps and start using 3D visualization tools.

- Download Gaia GPS or AllTrails: These apps allow you to toggle between "Slope Angle Shading" and "Topo Maps." This is vital for understanding whether a mountain range is "hikeable" or if you're looking at technical climbing terrain.

- Check the Rain Shadow: Use a map to see which side of the range you are on. In the West, the western slopes are usually lush and green (the "wet" side), while the eastern slopes are dry and desert-like (the "rain shadow"). This completely changes what gear you need to pack.

- Identify Public Lands: Most U.S. mountain ranges are managed by the Forest Service (USFS) or the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Use a map layer like "Public Lands" to see where you can legally camp for free—often called dispersed camping—versus where you need a permit for a National Park.

- Respect the Geology: If you’re heading into the Cascades, check the USGS Volcano Hazards Program. If you’re heading into the Rockies in winter, the CAIC (Colorado Avalanche Information Center) is your best friend.

The mountains don't care about your map, but your map can definitely keep you from getting stuck in a place you don't belong. America’s terrain is a messy, beautiful, and dangerous puzzle. Understanding the U.S. mountain ranges map is just the first step in solving it. Reach out to local ranger stations before any major trek; they have the boots-on-the-ground info that a satellite map will never show you. Take a paper map as a backup. Batteries die, but North America's geology isn't going anywhere anytime soon.