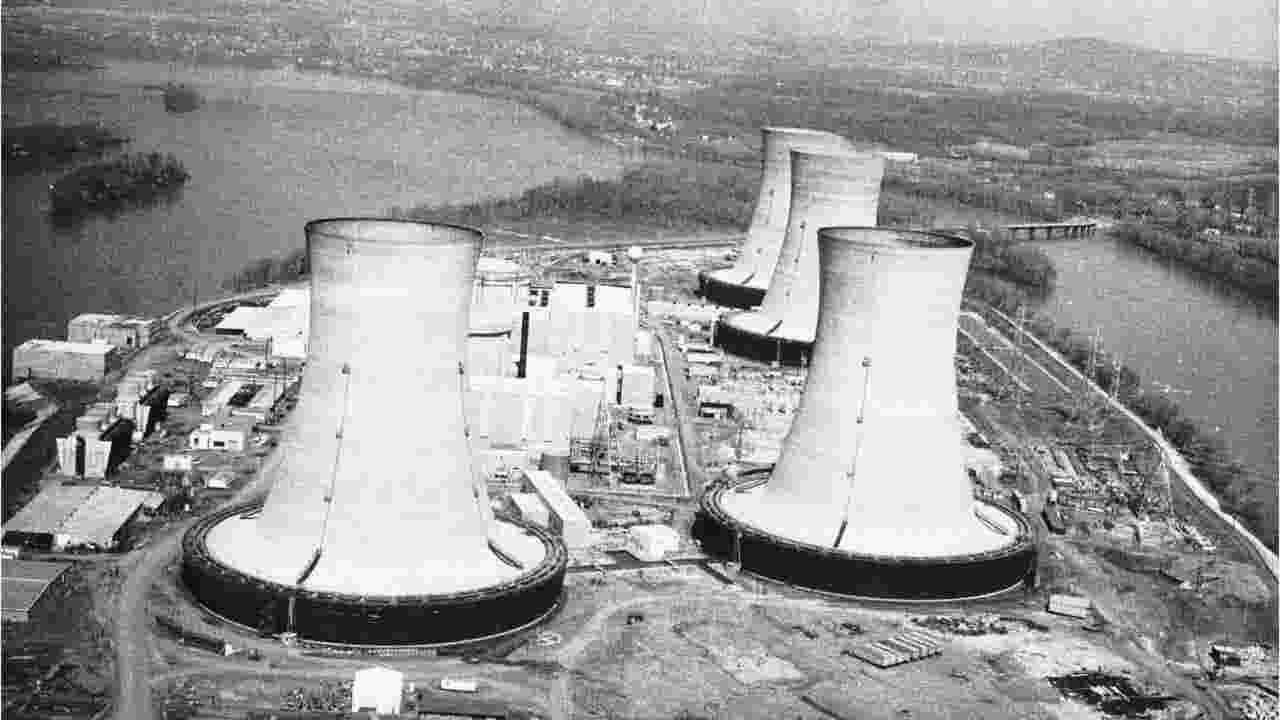

It was 4:00 AM on a Wednesday in Pennsylvania. Most people were sleeping, totally unaware that a cooling pump had just failed in Unit 2 of the Three Mile Island nuclear plant. It sounds like the start of a thriller movie, doesn't it? But for the folks living near Harrisburg in 1979, the Three Mile Island accident wasn't a plot point. It was a terrifying reality that changed how the world looks at energy forever.

Honestly, if you ask the average person what happened, they’ll probably mention a massive explosion or a cloud of deadly green gas. Neither of those things actually happened. The truth is much more subtle, technical, and—in a way—way scarier because it was caused by a series of tiny, avoidable human errors.

The Mechanical Glitch That Spiraled Out of Control

Everything started with a simple mechanical failure in the secondary cooling system. Basically, a valve failed to close. This should have been a minor hiccup. Nuclear plants are built with layers of safety systems specifically for this kind of stuff. But here’s where things got messy: the operators in the control room didn't realize the valve was stuck open.

A light on their dashboard suggested the command to close the valve had been sent, so they assumed it was closed. It wasn't.

Water—the stuff that keeps the nuclear fuel from melting into a puddle of radioactive lava—began pouring out of the system. Because the sensors were confusing, the operators actually turned off the emergency core cooling system. They thought the reactor had too much water. In reality, the core was uncovering and starting to cook.

It’s kind of wild to think about. You have some of the smartest engineers in the country staring at a control panel, and they’re doing exactly the opposite of what needs to be done because the interface was designed so poorly. This wasn't a "mad scientist" scenario. It was a "confused guy at a desk" scenario.

The "China Syndrome" Coincidence

Timing is everything in history. Just twelve days before the Three Mile Island accident, a movie called The China Syndrome hit theaters. It starred Jane Fonda and Michael Douglas, and the plot was—you guessed it—about a near-disaster at a nuclear power plant. One of the characters even mentions that a meltdown could render an area "the size of Pennsylvania" uninhabitable.

You can’t make this stuff up.

When the real-life sirens started blaring near the Susquehanna River, the public was already primed for a nightmare. Panic wasn't just likely; it was inevitable. Then-Governor Dick Thornburgh eventually advised pregnant women and preschool-aged children within five miles of the plant to evacuate. This led to about 140,000 people fleeing the area. Roads were packed. People were terrified.

The communication from Metropolitan Edison, the company running the plant, was... let's just say "not great." They were downplaying the situation while the NRC (Nuclear Regulatory Commission) was sounding the alarm about a "hydrogen bubble" inside the containment building that might explode. It turned out that bubble couldn't actually explode because there was no oxygen to ignite it, but by the time they figured that out, the PR damage was done.

What Actually Leaked?

Let's talk about the radiation. This is the part where facts usually get buried under fear.

Yes, radioactive gases were released. However, several independent studies, including ones from the Pennsylvania Department of Health and the EPA, concluded that the average dose to people living within ten miles was about 8 millirem. To put that in perspective, a single chest X-ray is about 6 millirem. You get more radiation from the sun during a cross-country flight than most neighbors got from the Three Mile Island accident.

🔗 Read more: Who is the founder of reddit: What most people get wrong about the site's origin

That doesn't mean it was "fine."

The psychological toll was massive. People lived with the fear of cancer for decades. While the official stance is that there were no deaths or injuries directly linked to the radiation, the loss of trust in the government and the nuclear industry was total. You can't just tell people "trust the science" when the science almost melted through the floorboards of their backyard.

The End of the Nuclear Renaissance

Before 1979, the U.S. was on track to build hundreds of nuclear reactors. After Three Mile Island, that momentum hit a brick wall. Construction costs skyrocketed because of new, much stricter safety regulations. Public opposition became a powerhouse movement.

It took 14 years and roughly $1 billion to clean up Unit 2. They had to use remote-controlled robots to survey the damage because the radiation levels inside the containment building were still way too high for humans. When they finally got a camera inside the core, they saw that about half of it had actually melted. It was much closer to a total catastrophe than the utility company had admitted at the time.

Lessons We Use Today (Actionable Insights)

We still live in the shadow of this event. If you work in tech, healthcare, or any high-stakes industry, the Three Mile Island accident offers a masterclass in what not to do.

- Prioritize UX in Safety Systems: The operators weren't stupid; their tools lied to them. Always ensure that "status" lights reflect the actual state of the hardware, not just the command sent to it.

- Over-Communicate During a Crisis: Met-Ed’s vague statements turned a technical failure into a social panic. If you’re managing a crisis, being transparent about what you don't know is just as important as sharing what you do know.

- Redundancy Isn't Just for Machines: You need "human redundancy." After TMI, the industry created the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations (INPO). This established a system where plants peer-review each other. Don't grade your own homework.

- Acknowledge the "Human Factor": Most "tech" disasters are actually "people" disasters. Training needs to focus on high-stress decision-making, not just rote memorization of manuals.

If you’re interested in seeing the site, you can still drive by. Unit 1 actually kept operating until 2019, which is a bit of a mind-trip when you realize it sat right next to the "dead" Unit 2 for forty years. Today, the towers stand as massive concrete ghosts of a future that never quite happened.

The best way to respect the history of the Three Mile Island accident is to look past the sensationalism and understand that safety is a constant work in progress. It’s never "finished."

To dig deeper into the actual data of the cleanup and the environmental impact, you should check out the official archives at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) or read the Kemeny Commission Report, which was the definitive investigation ordered by President Jimmy Carter. Those documents provide a raw look at the mistakes made and the technical hurdles overcome during the decade-long cleanup. Look for the "Report of the President's Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island" specifically for the most granular details on the control room failures.